Statement for the Record

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee:

I am pleased to present the Fiscal Year (FY) 2007 President's budget request for the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The FY 2007 budget estimate is $994,829,000, a decrease of $5,200,000 from the FY 2006 enacted level of $1,000,029,000, comparable for transfers proposed in the President's request.

Introduction

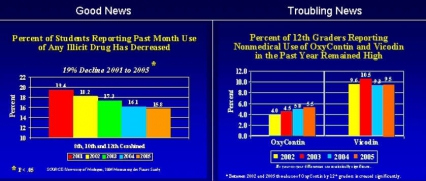

The National Institute on Drug Abuse, within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is once again pleased to report continuing declines in overall drug use among our Nation's youth. NIDA has focused much of its research on the vulnerable adolescent period of development, since this is when drug abuse typically takes hold and can bend a young life toward long-term drug abuse problems or addiction. Research findings elucidating the mechanisms of action and destructive consequences of drugs of abuse on the brain and body appear to be getting through to this population. For example, the 2005 Monitoring the Future (MTF) Survey of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders shows a dramatic 19% reduction in use since 2001. However, areas of significant concern remain, including the alarmingly high rates of non-medical use of painkillers among 12th graders, the high rates of stimulant abuse among 12th graders, and the spread of methamphetamine abuse to new geographic areas of the country.

Therefore, while we can acknowledge and appreciate the positive effects of evidence-based prevention and treatment efforts, we also recognize the need to keep pace with emergent problems. To this end, ongoing support of leading edge research by NIDA scientists continues to enhance innovative prevention and treatment interventions, while collaborations with other Institutes and public and private partners make optimal use of our research infrastructure.

Prescription Drug Abuse — The Problem With Painkillers

According to the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, nearly 3/4 of the estimated 6 million people aged 12 and older who reported non-medical use of prescription psychoactive drugs said they abuse pain relievers in particular, with young adults (18-25) showing the greatest increases in lifetime use from 2002-2004. Even younger populations are involved, revealed by findings from NIDA's 2005 MTF Survey.

NIDA is tackling this growing problem from multiple angles, seeking to understand the factors that have brought us to this point so that we may reverse negative trends and stop new ones from emerging. Underlying factors include the fact that opioids are now among the most commonly prescribed medications, that society is more accepting of using medications to treat all kinds of health problems, and that the Internet provides greater access to prescription drugs.

In response to these concerns, NIDA's new initiative on prescription opioids and treatment of pain is soliciting a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies from across the sciences. We will examine the basic mechanisms involved in pain and how their interaction with prescription painkillers influences addiction potential—for example, whether opiates are equally addictive to an individual in pain versus one who is not in pain. Research on the basic interactions between pain and opioid systems is needed to inform physicians about associated abuse risks and to guide their prescribing practices.

Other strategies for reducing prescription painkiller abuse include developing alternative pain medications and promoting better delivery systems for painkillers to minimize abuse potential. Recent studies have identified a subset of cannabinoid receptors (i.e., CB2 receptors) as promising new targets for treating chronic pain from nervous system injury. In addition, because of their lack of activity in brain reward centers and diminished abuse liability, novel CB2-based medications present an attractive alternative for treating chronic pain. Buprenorphine/naloxone, a recently approved medication for the treatment of opioid addiction, represents another approach. Acting on the same brain receptors as drugs like heroin and morphine, buprenorphine does not produce the same high, physical dependence, harsh withdrawal symptoms, or dangerous side effects. Further, its unique formulation with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, produces severe withdrawal symptoms in addicts who inject it to get high, thereby lessening the likelihood of diversion while maintaining desired therapeutic properties. NIDA is planning a multiple trial study to evaluate the effectiveness of buprenorphine in the treatment of the pain patient who is addicted to his/her pain medication and to help develop guidelines on how to treat these types of patients.

Genes, Environment, and Behavior

A person's individual genome, or genetic makeup, plays an important role in determining his or her vulnerability to or protection against addiction. Studies of heredity have shown that about 40-60 percent of predisposition to substance abuse can be attributed to genetics, with environment impacting how those genes function or are expressed. Addiction is a quintessential gene-x-environment interaction disease: that is, a person must be exposed to drugs (environment) to become addicted, yet exposure alone is not determinative—genes interact with this environment to create a vulnerability to addiction. Growing knowledge about the dynamic interactions of genes with the environment confirm addiction as a complex and chronic disease of the brain with many contributors to its expression in individuals.

NIDA is studying these interactions to see what they reveal about vulnerability to addiction and to other adverse effects of abused drugs. For example, one recent study found that carriers of a common variant of the COMT gene were more likely to exhibit psychotic symptoms and to develop schizophreniform disorder if they used marijuana. Thus, people with particular genes may suffer more harmful effects from drugs of abuse.

To expedite the translation of findings that could help identify the location of genes that confer vulnerability or protection, NIDA is supporting innovative research to help design, develop, and market technology to conduct rapid behavioral throughput screens for identifying genetic vulnerability using animal models of drug abuse and addiction. This information could then become part of a database of candidate genes for drug abuse, for eventual mapping and for targeted therapeutic application. Advances in genetics research in addiction are already suggesting ways to tailor our interventions to have the greatest impact. For example, a recent study showed that distinct alleles of the dopamine receptor gene led to different outcomes according to the type of smoking cessation therapy used—bupropion or nicotine replacement therapy. Such findings provide a glimpse of a future in which a patient's genetic background will be a major factor in selecting the most appropriate therapeutic course of action.

Other NIDA studies are also helping to unravel the ways in which environmental factors, such as stress, induce brain changes that interact with drugs of abuse and alter behavior. It is well known that stress is a major cause of relapse to drug abuse in recovering addicts and can prompt the release of a neurochemical, corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF). Recent research showed that in cocaine-exposed animals, stress-induced CRF triggered drug-seeking behavior, even as long as 3 weeks after exposure. This research highlights the concept of persistent brain changes leaving individuals vulnerable to certain relapse triggers like stress. Moreover, stress may be common to a variety of conditions, including depression, anxiety, and some forms of overeating and obesity. By revealing the precise brain mechanisms involved in stress, our research can lead to treatments that for these conditions.

We are also learning how environmental factors not only alter the expression but the structure of genes involved in brain function, which then influences an individual's behavior. Known as "epigenetics," this field gives researchers an opportunity to investigate gene-environment interactions, including the deleterious changes to brain circuits resulting from drug abuse. Understanding how drugs of abuse effect epigenetic changes may help in developing interventions to counter or prevent such changes. A recent study of demonstrated that cocaine caused significant structural changes to the DNA in regions containing genes implicated in shaping the brain's response to drugs of abuse; furthermore, in animals genetically engineered to minimize those changes, the rewarding effects of cocaine were dramatically reduced. These results show how gene-environment interactions can change the brain and drive behaviors associated with drug addiction. NIDA is supporting innovative research to help design, develop, and market technology to conduct rapid behavioral throughput screens for identifying gene/environment interactions.

Social Neuroscience

NIDA is targeting the influence of social factors both in individual and group decision-making. This focus is critical not just to understanding drugs of abuse but other health behaviors as well. For instance, a social neurobiological perspective is being applied in NIDA studies investigating the mechanisms underlying adolescents' increased sensitivity to social influences (i.e., peers) and decreased sensitivity to negative consequences of their behavior that together make them particularly vulnerable to drug abuse.

A recent NIDA request for research in the emerging field of social neuroscience is soliciting studies from basic to clinical science as we work to examine how neurobiology and the social environment interact in abuse and addiction processes (e.g., initiation, maintenance, relapse, and treatment). We now have the tools to see how genetics, epigenetics, and brain chemistry can change social behavior and how the social interactions of an individual can change his or her brain. For example, studies of early maternal behavior in animals demonstrated that offspring receiving low levels of care during their first week of life developed an over-responsive stress system that lasted a lifetime. In this case, genes responsible for regulating stress responses were "silenced" by environmental manipulation. Some of these changes can be reversed in adulthood by targeted intervention, making this research area ripe for developing approaches to counteract the effects of adverse environmental impacts, which in the case of stress are known to increase the risks for substance abuse.

We are also committed to efforts to better characterize "phenotypes" of social environments and to understand their interaction with other vulnerabilities, such as genetics. One approach could include strategies such as mapping community risk factors for drug use (e.g., parental practices, family structure, school systems, socio-economic status, neighborhood characteristics, and drug availability) and to use that knowledge to inform us about mediators of the social stressors that elevate risk for drug abuse. A better understanding of this relationship is relevant both for the treatment of drug addiction and for psychotherapeutic interventions for mental illnesses, which also involve social aspects of human behavior.

Drug Addiction Treatment Works

NIDA's research findings have demonstrated that drug addiction treatment works. Moreover, comprehensive treatments (i.e., those that include a combination of available medications, behavioral treatments, and job training and referral services) tailored to the needs of the individual patient have the highest success rates. We continue to work with the private sector to develop medications to use with behavioral therapies to treat drug addiction, and are pursuing collaborations with pharmaceutical companies to move novel and promising compounds forward to clinical evaluation. In addition, NIDA's initiative focusing on pilot clinical trials of new addiction medications will invigorate the field by helping investigators generate sufficient safety and efficacy data to support full-scale clinical trials and expedite the possible progression of novel medications to real-world use.

Over the past year, we have made great progress in identifying potential medications for treating drug addiction, including addiction to stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine. Several promising compounds have been identified in animal studies, and initial clinical efficacy for drug abuse has been demonstrated for medications marketed for other uses: disulfiram, prescribed for alcoholism; modafinil, for treatment of narcolepsy; and gamma-vinyl GABA (not marketed in the United States) and topiramate, both used to treat seizure disorders. Progress is also being made in the area of vaccine development for cocaine and nicotine addiction, and Rimonabant, a cannabinoid receptor blocker is a promising candidate for treating marijuana addiction. Close to being approved for marketing by the pharmaceutical industry as a weight loss aid, Rimonabant may also have the potential to prevent relapse to cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine abuse, and nicotine addiction. Marinol, another cannabinoid receptor agonist, may also show promise as a treatment for marijuana withdrawal symptoms.

Interventions are also needed to treat comorbid mental disorders and addiction. For example, given that an estimated 15-30 percent of patients with substance abuse problems also suffer from comorbid ADHD, as found in research studies, NIDA has launched a large clinical study in our Clinical Trials Network (CTN) to test whether treatment of ADHD with methylphenidate, in parallel with treatment for substance abuse, will improve outcomes in those who suffer from both conditions.

We are also developing drug abuse treatments for use in the criminal justice system. Our research findings show that drug treatment works even for people who enter it under legal mandate, with outcomes as favorable as for those who enter treatment voluntarily. To illustrate, in a Delaware Work Release study sponsored by NIDA, those who participated in prison-based treatment followed by aftercare were seven times more likely to be free of drugs after 3 years than those who received no treatment. Moreover, nearly 70 percent of those in the comprehensive drug treatment group remained arrest-free after 3 years—compared to only 30 percent in the no-treatment group. We are helping to integrate drug treatment into the criminal justice system and improve outcomes for offenders through our comprehensive Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (CJ-DATS) initiative, undertaken in collaboration with Federal, state, and local criminal justice partners.

NIDA research has demonstrated the value of drug addiction treatment programs in helping patients recover from the complex disease of addiction. Faith-based and community-centered programs are often part of long-term recovery, yet their effectiveness and role in delivering treatment needs to be studied more extensively. NIDA is conducting research to examine this role.

HIV/AIDS and Minority Disparities

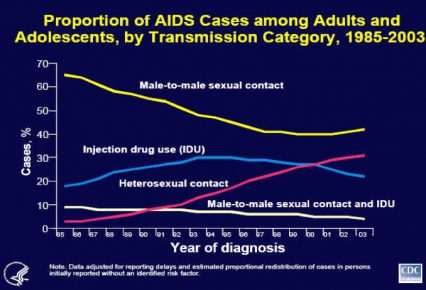

The latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that the HIV/AIDS epidemic is evolving, with drug abuse still a major vector in its spread. Progress in treating injection drug abuse has helped to decrease HIV transmission among this highly vulnerable population, influenced by a multi-pronged approach including community-based outreach to reduce risky behaviors and development of medications such as methadone and buprenorphine to treat injecting drug users. But while this approach has helped reduce U.S. cases from this route of transmission, other countries, such as Russia and Southeast Asia, continue to report that injection drug abuse accounts for a large proportion of their HIV/AIDS cases. Thus NIDA is supporting international studies to promote HIV prevention practices and use of medications to treat drug addiction. Depot-Naltrexone is one such possibility, since it is a long-acting opioid antagonist medication expected to soon receive approval for treatment of alcohol addiction. Because efforts to decrease drug abuse also modify the behaviors that can lead to HIV transmission, we believe strongly that drug abuse treatment is HIV prevention.

Early detection of HIV helps prevent HIV transmission and increase health and longevity. NIDA-supported research indicates that routine HIV screening, even among populations with prevalence rates as low as 1 percent, is as cost effective as screening for other conditions such as breast cancer and high blood pressure. These findings have important public health implications, but require efforts to increase HIV screening acceptability (similar to mammography) in order to be effective.

We are also deeply concerned about the disproportionate impact of HIV/AIDS on African Americans. For while they represent just 13 percent of the U.S. population, African Americans account for 42 percent of AIDS cases diagnosed since the start of the epidemic, according to CDC. In fact, data from the CDC's National Vital Statistics Report published in 2003 show that HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death among all African Americans 25Ð44 years old, ahead of heart disease, accidents, cancer, and homicide.

To address these disparities, NIDA is encouraging research on the nexus of drug abuse and HIV/AIDS among African Americans to understand the risk factors and the pathways between them and to develop culturally sensitive prevention and treatment programs for drug abuse and HIV/AIDS. We are committed to making sure this research is translated in a meaningful way.

From Bench to Bedside to Community

NIDA is proud of our myriad efforts to translate the results of our basic and clinical research on the brain and body effects, getting new treatments into the hands of providers who will use them, disseminating prevention messages to people who will hear them, and raising the awareness of people who can help change the course of drug abuse treatment in this country. Our audiences are many and include physicians, teens, teachers, judges, parents, and others.

Through our physician outreach initiative, we are funding efforts to develop strategies for primary care physicians to better identify and serve drug abusing patients through use of science-based screening and brief interventions. We are also supporting development of a pilot judicial training curriculum in Cook County, Illinois, to help criminal court judges understand the neurobiology of addiction and the effectiveness of treatment. The goal of this program is to better inform judicial decision-making with regard to substance-abusing offenders. These efforts will be applied to the Federal court system as well. We also support grants to evaluate results from drug courts to achieve optimal dissemination and improve outcomes, and we will soon publish a book of treatment principles for application with individuals involved in the criminal justice system.

Our education portfolio continues to grow and includes a wealth of materials, such as our NIDA Goes Back to School Initiative, a science education campaign to provide middle school students with information about how drugs work in the brain. An interactive website complements this effort, allowing students and teachers to easily obtain additional information about drugs of abuse. To help young people understand the risks of drug abuse leading to HIV infection, NIDA and our partnering organizations—including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the AIDS Alliance for Children, Youth, and Families, and the United Negro College Fund Special Programs Corporation—recently launched a multimedia educational campaign, including a public service announcement and website, to help young people "learn the link" between drug abuse and HIV infection. We are translating these materials into Spanish and making them culturally relevant for different populations.

We are also collaborating with our sister agency, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and with the National Institute of Mental Health on a new initiative to enhance the capacity of community-based providers of drug abuse treatment services. We continue to work with SAMHSA, supporting the development and dissemination of research-based products through their Addiction Technology Transfer Centers across the country, applying findings from our Clinical Trials Network and other research. And because addictive, psychiatric, and neurological disorders emerge from common neural substrates, a tremendous amount of inter-Institute collaboration has taken place—an approach we will continue to emphasize, given its ability to produce sharable findings and cost efficiencies.

Conclusion

Our investment in basic and clinical research has changed the way people view drug abuse and addiction in this country. We now know how drugs work in the brain, their health consequences, how to treat people already addicted, and what constitutes effective prevention strategies. As science advances, NIDA's comprehensive research portfolio is strategically positioned to capitalize on new opportunities. We continue to make great strides in translating and disseminating the products of our research, so they can be used in real communities by people who need them, providing front-line clinicians around the country with the tools needed to reduce drug abuse and addiction in our Nation. To make the most of scarce resources, we depend on a rigorous planning and priority-setting process that not only supports our strong commitment to reducing drug abuse and HIV transmission in this country, but extends to other health fields represented by NIH. Sustaining the momentum of our efforts will lead to even more discoveries that will improve the health and safety of all Americans.

Thank you, Mr. Chairman. I will be pleased to answer any questions the Committee may have.