Statement for the Record

Thank you, Mr. Chairman and members of the Subcommittee, for the opportunity to contribute to this important discussion. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), a component of the National Institutes of Health, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is the world's leading supporter of research on the health aspects of all drugs of abuse. The research we fund has taught us much about what drugs can do to the brain and how best to use science to approach the complex problems of drug abuse and addiction.

I want to focus my comments on what our research has taught us about the scope, pharmacology, and health consequences of cocaine abuse and addiction, particularly with regard to two forms of cocaine - powder and freebase (aka "crack") - and the effects of various routes of administration. My statement will support the scientific view that cocaine's effects vary depending on how it is administered. My statement will also make it clear that cocaine in all its forms poses serious health risks, including addiction.

Cocaine abuse remains a significant threat to the public health. Regarding specific questions surrounding powder versus crack cocaine, research consistently shows that the form of the drug is not the crucial variable; rather it is the route of administration that accounts for the differences in its behavioral effects.

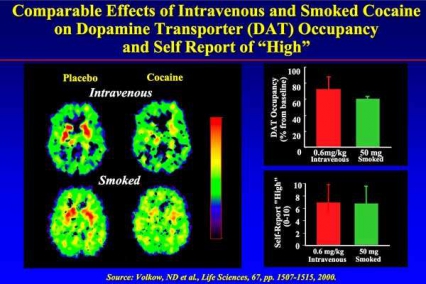

Research supported by NIDA has found cocaine to be a powerfully addictive stimulant. Like other central nervous system (CNS) stimulants, such as amphetamine and methamphetamine, cocaine produces alertness and heightens energy. Cocaine, like many other drugs of abuse, produces a feeling of euphoria or "high" by increasing the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain's reward circuitry. It does this by blocking dopamine transporters (DAT), which have the critical task of removing dopamine from in between neurons, thereby shutting off the neural signal once a rewarding stimulus is no longer present. The normal functioning of DAT is critical to the healthy operation of the brain's reward system, which allows us to register pleasure from everyday rewards. Cocaine, in any form, produces similar physiological and psychological effects once it reaches the brain, but the onset, intensity, and duration of its effects are directly related to the route of administration and to how rapidly cocaine enters the brain; the faster its entry the stronger its reinforcing effects.

Oral absorption is the slowest form of administration because cocaine has to pass through the digestive tract before it is absorbed into the bloodstream. Intranasal use, or snorting - the process of inhaling cocaine powder through the nostrils - leads to quicker absorption through the nasal tissue. Intravenous (IV) use, or injection, is faster still, introducing the drug directly into the bloodstream and heightening the intensity of effects. Finally, and similar to injection, the inhalation of cocaine vapor or smoke into the lungs is also a very effective method of delivering the drug into the bloodstream. Compared to the injection route, however, smoking produces quicker and higher peak blood levels in the brain -hence, a faster euphoria - and is devoid of the risks attendant to IV use, such as exposure to HIV from contaminated needles. Importantly, all forms of cocaine, regardless of route of administration, result in DAT blockade in the reward center of the brain (see Figure). This is why repeated use of any form and by any route can lead to addiction and other adverse health consequences.

Scope of the Problem

Although marijuana remains the most commonly used illicit drug in the country (an estimated 25.1 million past-year users 12 or older), according to the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), administered by HHS's Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA), 5.7 million (2.3 percent) persons aged 12 years or older used cocaine in the year prior to the survey, and more than 2 million (0.8 percent) were current (past month) cocaine users. This percentage has remained fairly intractable for the past 5 years, with little variance occurring among persons aged 12 or older.

In 2007, roughly 1.5 million persons 12 years or older (0.6%) used crack (cocaine freebase) in the past year, and 610,000 (0.2%) were current (past month) crack users. Crack was first added to the NSDUH in 1988, and over successive years of the survey, estimates of past-month use have never exceeded 0.3% of the population 12 and older. However, past-month use of crack among Blacks 12 or older in 2007, at 0.5%, reflects a prevalence much higher than in the White (0.2%), Hispanic (0.1%) or American Indian/Alaska Native (0.3%) populations.

The NIDA-supported Monitoring the Future (MTF) study, an annual survey that elicits information about drug use and attitudes among high school students, provides valuable information about the changing patterns of drug use in selected populations. The MTF reports that past year use of cocaine in any form has been essentially unchanged since 2003 among 12th, 10th, and 8th graders. Past-year abuse of cocaine (including powder and crack) was reported by 4.4% of 12th graders, 3.0% of 10th graders, and 1.8% of 8th graders in 2008. For crack cocaine, the rates were 1.6%, 1.3%, and 1.1%, respectively.

A decline has occurred in the number of people admitted to treatment for cocaine addiction, according to the Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), a SAMHSA-supported data system providing information about the number and characteristics of admissions at State-funded substance abuse treatment programs. Primary cocaine admissions have decreased from approximately 278,000 in 1995 (17% of all admissions reported that year) to around 234,700 (13%) in 2007. Smoked cocaine (crack) represented 72% of all primary cocaine admissions in 2007. Among smoked cocaine admissions, 49% were Black, 40% White, and 8% Hispanic, whereas a reverse pattern was evident among Blacks and Whites (23% and 54%, respectively, and 19% were Hispanic) for non-smoked cocaine.

In contrast to the generally downward or stable trends reflected in most nationally conducted surveys, other indicators appear to suggest that cocaine abuse may be on the rise in some localities. For example, one study looking at cocaine deaths in the State of Florida revealed a dangerous upward trend, with cocaine-related deaths nearly doubling from 2001 to 2005, from 1,000 to 2,000. The study also showed dramatic increases in the popularity of cocaine among the young and affluent, by all routes of drug administration. In addition, Department of Justice statistics demonstrate that the percentage of state and local law enforcement agencies that reported methamphetamine as their greatest drug threat declined between 2004 and 2007, but the percentage of these agencies that reported cocaine as their greatest drug threat increased overall during that time. These indicators are of grave concern to NIDA.

The Two Forms of Cocaine

The two forms of cocaine - powder and crack - correspond to two chemical compositions: the hydrochloride salt and the base form, respectively. The hydrochloride salt, or powdered form of cocaine, dissolves in water and when abused can be administered intravenously (by vein), intranasally, designated insufflation (through the nose), or orally. The "base" forms of cocaine include any form that is not neutralized by an acid to make the hydrochloride salt. Depending on the method of production, the base forms can be free-base or "crack". The medical literature is often ambiguous when differentiating between these two forms, which actually share similar properties when vaporized. In its "base" forms (freebase and crack), cocaine can be effectively smoked because it vaporizes at a much lower temperature (80°C) than cocaine hydrochloride (180°C). The higher temperature can result in chemical degradation of cocaine.

With regard to route of administration, the picture is not complete. Among those entering treatment in 2007 with cocaine as their primary drug, 72% (167,914) were in treatment for smoked cocaine (inhalation), and 28% (66,858) for cocaine used in another form. Of the latter, 81% reported insufflation as the route of administration, and 11% reported injection, so it is clear that powder cocaine is overwhelmingly inhaled. Moreover, it is widely accepted that the intranasal route of administration is often the first way that many cocaine-dependent individuals use cocaine.

Acute Effects of Cocaine

Cocaine's stimulant effects appear almost immediately after a single dose and fade away within minutes to hours, depending on route of administration and dose. Taken in small amounts (up to 100 milligrams), cocaine usually makes the abuser feel euphoric, energetic, talkative, and mentally alert, especially to the sensations of sight, sound, and touch. It can also temporarily decrease the perceived need for food and sleep. Some abusers find that the drug helps them to perform simple physical and intellectual tasks more quickly, while others can experience the opposite effect.

The short-term physiological effects of cocaine include constricted blood vessels, dilated pupils, and increased temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure. Larger amounts (several hundred milligrams or more) intensify the abuser's high but may also lead to erratic, psychotic and even violent behavior. These abusers may experience tremors, vertigo, muscle twitches, paranoia, or, with repeated doses, a toxic reaction closely resembling amphetamine poisoning. Some cocaine abusers report feelings of restlessness, irritability, and anxiety. In rare instances, sudden death can occur on the first use of cocaine or unexpectedly thereafter. Cocaine-related deaths are often a result of cardiac arrest or seizures followed by respiratory arrest. While tolerance to the "high" can develop, abusers can also become more sensitive to cocaine's adverse psychological or physiological effects with repeated doses.

Medical Consequences of Cocaine

Cocaine abuse can cause significant medical complications, both acutely and after repeated use. Some of the most common stem from cardiovascular effects, including disturbances in heart rhythm and heart attacks; respiratory effects such as chest pain and respiratory failure; neurological effects, including strokes, seizures, and headaches; and gastrointestinal complications, including abdominal pain and nausea. Because cocaine has a tendency to decrease appetite, chronic abusers may also become malnourished. Different modes of administration can induce different adverse effects. Regularly insufflating ("snorting") cocaine, for example, can lead to loss of the sense of smell, nosebleeds, problems with swallowing, hoarseness, a chronically runny nose, and damage to the nasal septum; and ingesting cocaine can cause severe bowel gangrene due to reduced blood flow. Research has also revealed a potentially dangerous interaction between cocaine and alcohol, as evidenced by enhanced negative consequences when these substances are taken in combination.

Cocaine abuse can cause addiction. Cocaine is a powerfully addictive drug. Cocaine's stimulant and addictive effects are thought to be mainly a result of its effects on the dopamine transporter, a brain protein that regulates dopamine concentrations in the vicinity of nerve cells. Cocaine blocks the transport system, leading to a supraphysiological excess of dopamine in the brain. With repeated use, adaptation to the surge of dopamine sets in, and cocaine abusers often develop a rapid tolerance to the "high," sometimes referred to as tachyphylaxis. That is, even while the blood levels of cocaine remain elevated, the pleasurable feelings begin to dissipate, causing the user to crave more. This effect often leads to the compulsive pursuit and use of the drug, despite devastating consequences - the essence of addiction. Indeed, a recent study indicates that about 5% of recent-onset cocaine abusers become addicted to cocaine within 24 months of starting cocaine use. The risk of cocaine addiction, however, is not distributed randomly among recent-onset abusers. For example, in one study looking at a 2-year period, female initiates were three to four times more likely to become addicted to cocaine than males, and non-Hispanic Black/African American initiates were approximately nine times more likely to become addicted to cocaine than non-Hispanic Whites. Importantly, this excess risk was not attributable to crack-smoking or injecting cocaine.

The use and abuse of illicit drugs, including cocaine, is one of the leading risk factors for new cases of HIV. Cocaine abusers who inject the drug put themselves at increased risk for contracting such infectious diseases as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis through the use of contaminated needles and paraphernalia. Crack smokers constitute another high-risk group for HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases. Research has long shown the strong epidemiological relationship between crack cocaine smoking and HIV, which appears to be due mainly to the greater frequency of high-risk sexual practices in the population.

Additionally, hepatitis C virus (HCV) has spread rapidly among injection drug users; studies indicate approximately 26,000 new acute HCV infections occur annually, of which approximately 60% are estimated to be related to intravenous drug use.

Prenatal exposure to cocaine requires urgent attention. Among pregnant women aged 15 to 44 years, 5%, or 135,000 women, used an illicit drug in the past month, according to combined 2006 and 2007 NSDUH data. Thus, an estimated 135,000 babies were exposed to abused psychoactive drugs before they were born. In 2002, compared to non-pregnant admissions, pregnant women aged 15 to 44 entering drug abuse treatment were more likely to report cocaine than other illicit drugs (22% vs. 17%) as their primary substance of abuse.

Babies born to mothers who abuse drugs during pregnancy can suffer varying degrees of adverse health and developmental outcomes. This is likely due to a confluence of interacting factors that frequently characterize pregnant drug abusers. Among these are poly-substance abuse, low socioeconomic status, poor nutrition and prenatal care, and chaotic lifestyles. These factors have made it difficult to tease out the contribution of the drug itself to the overall outcome for the child.

However, with the development of sophisticated instruments and analytical approaches, several findings have now emerged regarding the impact of in utero exposure to cocaine; notably, these effects have not been as devastating as originally believed. They include a greater tendency for premature births in women who abuse cocaine. In addition, recent follow-up study of 10-year-old children who were prenatally exposed uncovered subtle problems in attention and impulse control, placing them at greater risk of developing significant behavioral problems as cognitive demands increase. Still, estimating the full extent of the consequences of maternal cocaine (or any drug) abuse on the fetus and newborn remains a challenging problem, one reason we must be cautious when searching for causal relationships in this area, especially with a drug like cocaine. NIDA is supporting additional research to understand this relationship and to determine if any other subtle, or not so subtle, short- or long-term outcomes can be attributed to prenatal cocaine exposure.

Treatment

Currently, the most effective treatments for cocaine addiction are behavioral therapies, which can be delivered in both residential and outpatient settings. Several approaches have shown efficacy in research-based and community programs, including (1) cognitive behavioral therapy, which helps patients recognize, avoid, and cope with situations in which they are most likely to abuse drugs; (2) motivational incentives, which use positive reinforcement, such as providing rewards or privileges, for staying drug free or for engaging in activities, such as attending and participating in counseling sessions, to encourage abstinence from drugs; and (3) motivational interviewing, which capitalizes on the readiness of individuals to change their behavior and enter treatment, performed at intake to enhance internal motivation to actively engage in treatment.

To date, no medication is approved for the treatment of cocaine addiction. Consequently, NIDA is aggressively evaluating several compounds, including some already in use for other indications (e.g., epilepsy or narcolepsy). In addition, NIDA-supported investigators have recently made significant progress toward the development of a vaccine, which can elicit specific antibodies to block the access of cocaine into the brain and thus its rewarding effects. These and others have shown promise for treating cocaine addiction and preventing relapse. Ultimately, the integration of both types of treatments, behavioral and pharmacological, will likely prove the most effective approach for treating cocaine (and other) addictions.

The same treatment principles that have proven effective in the general population should also be applied among incarcerated individuals. Approximately half of federal and state prisoners are beset with drug abuse or addiction problems (a rate more than 4 times that of the general population), and yet fewer than 20 percent of those who need treatment get it. We know from research that the enforced abstinence that occurs in prison does not "cure" a drug-addicted person, and that treatment within the criminal justice system, particularly when followed by ongoing care during the transition back to the community, reduces drug abuse and criminal recidivism and offers the best alternative for interrupting the vicious cycle of drug abuse and crime which is associated with economic costs and societal burden.

This concludes my statement. Thank you for the opportunity to present this information to you.