Thank you for inviting the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services, to participate in this forum and contribute what I believe will be useful insight into the growing public health problem of prescription drug abuse in this country.

Introduction to the Problem

In 2009, 7 million Americans reported current (past month) nonmedical use * of prescription drugs—more than the number using cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, and inhalants combined 1. National surveys show that the number of new abusers of several classes of prescription drugs increased markedly in the United States in the 1990s 2, continuing at high rates during the past decade—abuse of prescription drugs now ranks second (after marijuana) among illicit drug users 3. Perhaps even more disturbing, approximately 2.2 million Americans used pain relievers nonmedically for the first time in 2009 (initiates of marijuana use were 2.4 million).

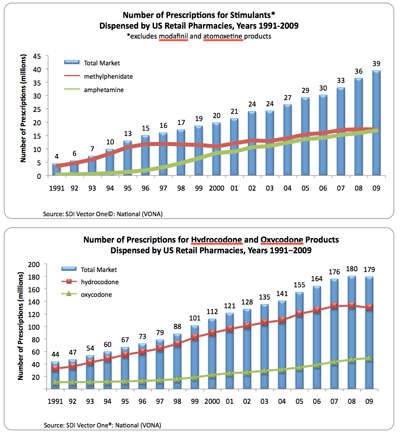

So what is behind this high prevalence and incidence? As expected, the motivations vary by age, gender, and other factors 4, which also likely include greater availability. The number of prescriptions for some of these medications has increased dramatically since the early 90's: more than 8 -fold for stimulants, and 4 -fold for opioids (figure) 5. Other contributors may be a consumer culture amenable to taking a pill for what ails you and the perception that abusing prescription drugs is less harmful than illicit ones 6. This is not the case: prescription drugs act directly or indirectly on the same brain systems affected by illicit drugs; thus their abuse carries substantial abuse and addiction liabilities and can lead to a variety of other adverse health effects.

NIDA therefore continues to support research to decrease prescription drug abuse, including pursuing medications that have little or no addiction potential. We know our approach must be balanced, so that people suffering from chronic pain, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, or other illnesses can get the relief they need while minimizing abuse potential.

Effects on the Brain and Body

The three broad categories of psychotropic prescription drugs with abuse liability include opioid analgesics, stimulants, and central nervous system (CNS) depressants. How they work is described briefly below:

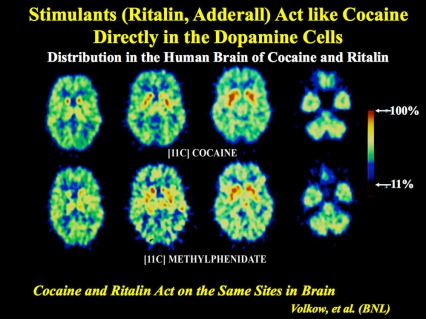

- Stimulants, prescribed for ADHD and narcolepsy, include drugs such as methylphenidate (e.g. Ritalin, Concerta) and amphetamine (e.g. Adderall). These prescription medications stimulate the central nervous system, with effects similar to but more potent than caffeine. When taken orally, as prescribed, these stimulants elicit a gradual and sustained increase in the neurotransmitter (brain chemical) dopamine, which produces the expected therapeutic effects seen in many patients. In people with ADHD, stimulant medications generally have a calming and "focusing" effect, particularly in children. However, because these medications affect the dopamine system in the brain (the reward pathway), they are also similar to drugs of abuse—particularly when they are taken at doses or by routes other than what is ordinarily prescribed. For example, methylphenidate is similar to cocaine, in that it binds to similar molecular targets in the brain, thereby increasing dopamine in reward circuits. When administered intravenously, both drugs cause a rapid and large increase in dopamine, which is experienced as a rush or high. For those who abuse stimulants, the range of adverse health consequences includes risk of dangerously high body temperature, seizures, and cardiovascular complications.

- Opioids, mostly prescribed to treat moderate to severe pain, include drugs such as hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin) and oxycodone (e.g., OxyContin). Opioids act on the brain and body by attaching to specific cell surface proteins called opioid receptors, which are found in the brain, spinal cord, gastrointestinal tract and other organs. When these drugs attach to certain opioid receptors, they can attenuate the perception of pain and its attendant suffering. These drugs also can induce euphoria by indirectly boosting dopamine levels in the brain regions that influence our perceptions of pleasure. This feeling is often intensified by abusers who snort or inject the drug, amplifying its euphorigenic effects and increasing the risk for serious medical consequences, such as respiratory arrest, coma, and addiction 7. Combining opioids with alcohol or other CNS depressants can exacerbate these consequences.

- CNS depressants, typically prescribed for the treatment of anxiety, panic, sleep disorders, acute stress reactions, and muscle spasms, include drugs such as benzodiazepines (e.g, Valium, Xanax) and barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbitol)—which are sometimes prescribed for seizure disorders. Most CNS depressants act on the brain by affecting the neurotransmitter gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), which works by decreasing brain activity. CNS depressants enhance GABA's effects and thereby produce a drowsy or calming effect to help those suffering from anxiety or sleep disorders. These drugs are also particularly dangerous when mixed with other medications or alcohol; overdose can suppress respiration and lead to death. The newer non-benzodiazepine sleep medications, such as zolpidem (Ambien), eszopiclone (Lunesta), and zalepon (Sonata), have a different chemical structure, but act on some of the same brain receptors as benzodiazepines and so may share some of the risks—they are thought, however, to have fewer side effects and less dependence potential.

Finally, over-the-counter (OTC) medications, such as certain cough suppressants, sleep aids, and antihistamines, can also be abused for their psychoactive effects. Cough syrups and cold medications are the most commonly abused OTC medications; nearly 6 percent of 12th-graders reported abusing cough medicine to get high in 2009 8. At high doses, dextromethorphan—a key ingredient found in cough syrup—can act like PCP or ketamine, producing dissociative or out-of-body experiences, and sometimes confusion, coma, and even death. Further, OTC medications often contain aspirin or acetaminophen (e.g., Tylenol), which can be toxic to the liver at high doses. OTC medications combined with any of the prescription drug types described above can intensify these dangers.

Troubling Signs of a Growing Problem

Selected indicators of the prescription drug and OTC medication abuse in this country include the following:

- Treatment admissions for opiates other than heroin rose from 19,870 in 1998 to 111,251 in 2008, over a 450-percent increase 9.

- The number of fatal poisonings involving prescription opioid analgesics more than tripled from 1999 through 2006, outnumbering total deaths involving heroin and cocaine 10.

- The Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN), which monitors emergency department (ED) visits in selected areas across the Nation, estimates that in 2008, roughly 305,000 ED visits involved nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers; 19,000 involved CNS stimulants; and 325,000 involved CNS depressants (anxyiolytics, sedatives, and hypnotics). Over half involved more than one drug. These numbers have more than doubled for pain relievers, and nearly doubled for stimulants and CNS depressants since 2004.

- ED visits related to zolpidem (Ambien)—one of the most popular prescribed non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in the United States—also more than doubled during this period, from about 13,000 in 2004 to about 28,000 in 2008.

Trends in Prescription Drug Abuse—Who Is Abusing What?

Latest trends show that adolescents and young adults may be especially vulnerable to prescription drug abuse, particularly opioids and stimulants.

Data from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicate that rates of prescription drug use were highest among young adults 18 to 25, with 6.3 percent reporting nonmedical use in the past month 11. That said, earlier data on past-year users of any prescription psychotherapeutic drug, prevalence of dependence or abuse is higher for the 12-17 year-old age group than for young adults (15.9 vs. 12.7 percent) 12. In this youngest age group, females exceed males in the nonmedical use of all psychotherapeutics, including pain relievers, tranquilizers, and stimulants, and are more likely to be dependent on stimulants 13.

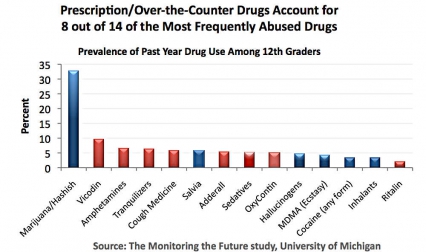

Moreover, according to the Monitoring the Future survey (MTF), prescription and over-the-counter drugs comprised 8 of the top 14 categories of drugs abused by 12th graders in 2009. And while many medications can be abused, opioids display particularly disturbing abuse rates. The MTF shows, for example, that the rate of nonmedical use of Vicodin and OxyContin has remained unchanged for several years, with nearly 1 in 10 high school seniors reporting nonmedical use of the former and 1 in 20 of the latter 14.

Also of concern is the diversion of stimulants, particularly ADHD medications among students, who are using them to increase alertness and stay awake to study 15. The growing number of prescriptions written for this diagnosis has led to dramatically greater availability of stimulant medications with potential for diversion. For those who take these medications to improve properly diagnosed mental disorders, they can markedly enhance a patient's quality of life. However, prescription stimulants are increasingly being abused for nonmedical conditions or situations (e.g., to get high; as a cognitive enhancer), which poses potential health risks, including addiction, cardiovascular events, and psychosis 16.

Why Do They Do It?

The far-ranging scope of prescription drug abuse in this country stems not only from the greater prescribing of medications, but also from misperceptions of their safety when used nonmedically or by someone other than the prescription recipient. Among the latter, many are taking prescription drugs for their intended purposes, such as to relieve pain in the case of prescription opioids, or to enhance alertness in the case of ADHD medications but without a doctor's supervision 17. Indeed, students and even some parents see nothing wrong in the abuse of stimulants to improve cognitive function and academic performance. In fact, being in college may even be a risk factor for greater use of amphetamines or methlyphenidate nonmedically, with reports of students taking pills before tests and of those with prescribed medications being approached to divert them. Pain relievers show a similar link with regard to access, evidence also suggesting that parents sometimes provide their children with prescription medications to relieve their discomfort. When asked how prescription narcotics (opioids) were obtained for nonmedical use, more than half of 12th-graders said they were given the drugs or bought them from a friend or relative 18.

Nonmedical use among children and adolescents is particularly troublesome given that adolescence is the period of greatest risk not only for drug experimentation but also for developing addiction. At this stage the brain is still developing, and exposure to drugs could interfere with these carefully orchestrated changes. Research also shows adolescents abusing prescription drugs are twice as likely to have engaged in delinquent behavior and nearly three times as likely to have experienced an episode of major depression as teens who did not abuse prescription medications over the past year. Finally, several studies link the illicit use of prescription drugs with increased rates of cigarette smoking, heavy drinking, and marijuana and other illicit drug use in adolescents and young adults in the United States. Thus, prescription drug abuse may be part of a pattern of harmful behaviors engaged in by those at risk for substance use and other mental disorders.

Older adults represent another area of concern. For although this group currently comprises just 13 percent of the population, they account for more than one-third of total outpatient spending on prescription medications in the United States 19. Older patients are more likely to be prescribed long-term and multiple prescriptions, which could lead to misuse (i.e., unintentionally using a prescription medication other than how it was prescribed) or abuse (i.e., intentional nonmedical use).

Various reasons underlie why older adults may misuse or abuse prescription drugs. Cognitive decline, combined with greater numbers of medications and complicated drug-taking regimens may lead to unintentional misuse. Alternatively, those on a fixed income may intentionally use another person's remaining medication to save money. Because older adults also experience higher rates of other illnesses as well as normal changes in drug metabolism, it makes sense that even moderate abuse or unintentional misuse of prescription drugs by elderly persons could lead to more severe health consequences. Therefore, physicians need to be aware of the possibility of abuse and to discuss the health implications with their patients and/or their caretakers.

Intervening with Prescription Drug Abusers: Different Approaches Needed

Because they can greatly benefit health as well as pose risks, prescription drugs present several challenges in how best to guard against their abuse. A nuanced approach is needed, tailored to particular user groups and their varied motivations. For patients and their doctors, the issues can quickly become complex and difficult to manage, as physicians may need to decide whether presenting symptoms indicates a need to increase the dose of an opioid analgesic to adequately manage pain, or signal a potential drug abuse problem.

By asking about all drug abuse, physicians can help their patients recognize when a problem exists, set recovery goals, and seek appropriate treatment. More than 80 percent of Americans had contact with a health care professional in the past year 20, placing them in a unique position not only to prescribe medications, but also to identify potential problem use of prescription drugs and prevent it from escalating to abuse and addiction. Screening for prescription drug abuse can be incorporated into routine medical visits, with brief interventions or referrals for patients who need them. To that end, NIDA has recently deployed NIDAMED, a physician outreach program that includes user friendly online tools designed to help primary-care physicians screen their patients for alcohol, tobacco and illicit and nonmedical prescription drug use.

And while preventing or stopping prescription drug abuse is an important part of patient care, healthcare providers should not avoid prescribing stimulants, CNS depressants, or opioid pain relievers if needed. Underprescribing opioid pain relievers, such as hydrocodone or oxycodone, can result in needless suffering and diminished quality of life for patients with legitimate medical needs. For their part, patients can take steps to enÂsure that they use prescription medications appropriately, and always discuss any and all drug use, including prescription and OTC medications, with their doctors.

What NIDA is Doing

To stay abreast of who is using and why, NIDA-supported researchers continue to gather information about the latest trends through large-scale epidemiological studies investigating the patterns and sources of nonmedical use, particularly in high school and college students. These years are often when young people initiate or increase their abuse of prescription and other drugs. Identifying trends as soon as they begin to surface in the population helps NIDA continue to lead the effort to surmount increasing abuse.

With the growing elderly population and the many returning injured veterans, it will be critical to better understand how to effectively treat people with chronic pain, which factors may predispose someone to become addicted to prescription pain relievers, and what can be done to prevent it among those at risk. NIDA is bolstering efforts to test and evaluate interventions targeting prescription drug abuse, tailoring them according to type of medication and reason for its abuse. NIDA will continue to use a multi-pronged strategy intended to complement and expand our already robust portfolio of basic, preclinical, and clinical research and educational and outreach initiatives to ameliorate the prescription drug phenomenon.

Medications Development

NIDA is leading efforts in the treatment of addiction to prescription pain relievers, viewing the discovery of effective medications for pain (with less abuse potential) and for addiction a public health priority. In this regard, the following show promise:

- Pain medications that do not act through opioid receptors. Compounds that activate cannabinoid type 2 receptors, located largely outside of the brain, have been shown to inhibit acute, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain. Similarly, non-neuronal brain cells known as glia have recently been shown to play a key role in pathological pain states and may serve as a novel target for pain medications.

- Suboxone—a buprenorphine/naloxone combination—a medication developed with NIDA support to treat opioid addiction. It reduces cravings, withdrawal symptoms, and is well tolerated by patients—and it can be prescribed by certified physicians in an office setting. Research suggests that it may also provide pain relief, but with diminished abuse liability and a larger safety margin than some other pain medications.

- Depot, or long-acting, formulations of medications, including naltrexone and buprenorphine. These versions lend to better compliance because their effects can last for weeks rather than hours or days (e.g., one dose can last 6-8 weeks). Thus, patients do not need to motivate themselves daily to stick to a treatment regimen, and sustained-released formulations decrease the potential for diversion and abuse, since there are no take-home, daily medications. A depot form of naltrexone, already approved for alcohol addiction, is showing remarkable promise in clinical trials for heroin addiction, increasing abstinence, treatment retention, and decreasing craving. Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these medications in treating addiction to opioid pain medications.

Unfortunately, at this time, there are still no medications proven effective for treating stimulant addiction. However, NIDA is supporting a number of studies on medications with potential in this regard.

Education and Outreach

Education is a critical component of any effort to curb the abuse of prescription medications and must target every segment of society. Because prescription drugs are safe and effective when used properly and are broadly marketed to the public, the notion that they are also harmful and addictive when abused can be a difficult one to convey. Along with advancing addiction awareness, prevention, and treatment in primary care practices through our NIDAMED initiative, NIDA is continuing the work of its Centers of Excellence for Physician Information to educate and enlighten physicians-in-training from diverse specialties. NIDA is also reaching out to teens with a new initiative known as PEERx, created to provide educators, mentors, student leaders, and teens with science-based information about the harmful effects of prescription drug abuse on the brain and body. In a more general vein, we will continue our close collaborations with the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and other Federal agencies, as well as professional associations with a strong interest in preserving public health.

Conclusion

Prescription drug abuse is not a new problem, but one that deserves renewed attention. It is imperative that as a Nation we make ourselves aware of the consequences associated with abuse of these medications. For although prescription drugs can be powerful allies, they also pose serious health risks related to their abuse, which can lead to addiction and to death. It will be a question of balance so that people suffering from chronic pain, ADHD, or anxiety can get the relief they need while minimizing the potential for abuse.

Consistent with NIDA's mission, our response has been framed by our commitment to translate what we know from research to help the public better understand drug abuse and addiction, and to develop more effective strategies for their prevention and treatment.

References

*The terms "prescription drug abuse" and "nonmedical use" are used interchangeably in this document and are based on the definitions used by most national surveys measuring nonmedical use (i.e., the intentional use of an approved medication without a prescription, in a manner other than how it was prescribed, for purposes other than prescribed, or for the experience or feeling the medication can produce). Misuse refers to unintentional use of an approved medication in a manner other than how it was prescribed.

1 SAMHSA. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586Findings). Rockville, MD: SAMHSA.

2 SAMHSA (2003). Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-22, DHHS Publication No. SMA 03-3836). Rockville, MD: SAMHSA

3 Ibid.

4 Boyd, C.J., McCabe, S. E., Cranford, J.A., Young, A. (2006) Adolescents' Motivations to Abuse Prescription Medications. Pediatrics. 118: 2472-80.

5 Source: SDI's Vecton One®: National.

6 Partnership for a Drug Free America. (2009) The Partnership Attitude Tracking Study (PATS) Teens 2008 Report.

7 Abuse related to using alternate routes of administration pertains to other classes of prescription medications as well and can lead to serious medical consequences.

8 Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2010). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2009 (NIH Publication No. 10-7583). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

9 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 1998-2008. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services, DASIS Series: SÐ50, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 409-4471, Rockville, MD, April 2010.

10 Margaret Warner, Ph.D.; Li Hui Chen, M.S., Ph.D.; and Diane M. Makuc, Dr.P.H. Increase in Fatal Poisonings Involving Opioid Analgesics in the United States, 1999-2006. NCHS Data Brief:No 22; Sept 2009.

11 SAMHSA. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586Findings).. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA.

12 See Tables 6.4 A and 6.4 B http://oas.samhsa.gov/prescription/AppD.htm.

13 Cotto et al. Gender effects on drug use, abuse, and dependence: an analysis of results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Gender Medicine, October, 2010.

14 Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2010). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2009 (NIH Publication No. 10-7583). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

15 Rabiner DL, Anastopoulos AD, Costello EJ, Hoyle RH, McCabe SE, Swartzwelder HS. The Misuse and Diversion of Prescribed ADHD Medications by College Students. Journal of Attention Disorders 13: 144-153, 2009.

16 McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical use, illicit use, and diversion of abusable prescription drugs. J Am Coll Health 54(5):269-78, 2006.

Garnier LM, Arria AM, Caldeira KM, VincentKB, O'Grady KE, Wish ED. Sharing and selling of prescription medications in a college student sample. J Clin Psychiatry 71(3):262-269, 2010.

17 McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, et al. Motives, diversion and routes of administration associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Addict Behav. 32(3):562-575, 2007.

McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical use, illict use and diversion of prescription stimulant medication. J Psychoactive Drugs 38(1):43-56, 2006.

18 Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2010). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2009 (NIH Publication No. 10-7583). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

19 Simoni-Wastilla L and Keri Yang H. Psychoactive drug abuse in older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 4(4):380-394, 2006.

20 National Center for Health Statistics, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2009) Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 10, Number 242.DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 2010-1570. Hyattsville, MD.