Details

Contact

United States

Meeting Summary

I - Introduction and Goals

In July and August of 2010, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) convened four meetings on the state of the knowledge regarding the evaluation of large scale multi-level, multi-site prevention interventions. The specific purpose of these four meetings was to obtain the advice and consultation of researchers, evaluators and funders on state-of-the-art methodologies for national assessments of large-scale, multi-level, multi-site prevention trials (MMPTs). In recognition of the complexity of the science and the universe of potential partners involved, each meeting focused on the areas of expertise and experiences of the participants in working with MMPTs. The following were the titles for each meeting:

- Perspectives from Researchers – July 23, 2010

- Perspectives from Large-Scale Evaluators – July 29, 2010*

- Perspectives from Cross-State Evaluators – August 2, 2010

- Perspectives from Program Officials with Large Data Bases – August 6, 2010

*For the purpose of these four meetings, Researchers was defined as one who was funded to conduct a controlled trial (e.g., RCT or strong quasi-experimental design) of a theory-based prevention intervention or operating system, whereas an Evaluator was defined as one who has conducted evaluations of Federal or State funded prevention intervention programs or systems.

It is hoped that the information in this combined report from the four meetings will be a resource for community, State and federal program planners and evaluators following covered areas: overarching issues, logic model, design, measurement, implementation and process evaluation, and analysis.

The impetus for these meetings was the language in the 2010 and 2011 National Drug Control Strategy, which described the proposed Prevention Prepared Communities (PPC) program. This proposed program would be a next step in making the visions of current successful federally-funded grant programs such as Strategic Prevention Framework-State Incentive Grants (SPF-SIGs), Drug Free Communities (DFC), Safe Schools Healthy Students (SSHS) and others a reality through a coordinated multi-level approach to prevention. The intent of the Strategy was to:

“Focus on youth to conduct epidemiological needs assessments; create a comprehensive strategic plan; implement evidence-based, developmentally appropriate prevention services through multiple venues; and address common risk factors for mental, emotional, and behavioral problems, including substance abuse and mental illness. Agencies would coordinate their grants and technical assistance such that communities and the youth in them are continuously surrounded by protective factors rather than protected only in a single setting or at a single age (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/ondcp/policy-and-research/ndcs).”

Unlike other multi-level, multi-site prevention trials (MMPT), the vision of the Strategy plan was characterized by new cooperation and collaboration at the three levels involved in implementing this program:

- At the Federal level, the multiple agencies involved would partner to streamline planning, budget, and management requirements for the PPC program, including application, review, funding and reporting processes.

- At the State level, a State Prevention Coordinator(s) would coordinate cross-agency collaborations and provide data and programmatic technical assistance (TA) and other guidance to local communities on assessing needs, selecting and implementing interventions and evaluating for continuous quality improvement and outcome reporting.

- at the local level, the community would select and implement evidence-based mental, emotional and behavioral (MEB) health promotion/prevention interventions based on empirically determined needs and resources in conjunction with a thorough planning process and demonstrated capabilities to address their local problems.

This cooperation and collaboration would facilitate the development of a sustainable National Prevention System (NPS) for the prevention of substance use and other associated MEB problems among children and youth.

The mention of the PPC in the National Strategy as the first step towards a NPS prompted NIDA to begin considering the many issues that would be involved in the evaluation of such a large MMPT. The four meetings on which this report is based were an attempt to bring the scientific knowledge, practice and policy experiences supported by federal and state governments to bear on those issues.

Seven elements of evaluation planning and implementation for large-scale, multi-level, multi-site health promotion/prevention trials emerged from these meeting. All of these elements surfaced in more than one of the four meetings and some were discussed in all four meetings. In general, the themes provide a forward looking view of how to design and manage an evaluation, starting with considering what has been learned from other MMPTs. This perspective views prior evaluations as learning grounds for new large evaluations. Many of the federal programs that have been supported over the last 10 years were mentioned as sources of information on structure and process and data on outcomes and findings useful in the planning process. Of particular relevance was the development of research partnerships and coalitions. Much of this discussion emphasized the importance of including community members and leaders in the planning of evaluations as they are valuable sources of information about the community, its resources and problems and its prevention goals. Information such as this is critical to planning a logic model of how all aspects of the evaluation will work together in facilitating the desired outcome.

Research and evaluation expertise was also discussed as a necessary to the planning of these large-scale, multi-level, multi-site, prevention trials. This is especially the case with the development of core measures, data systems, and specification of evaluation questions. Thus, a partnership approach to designing, conducting and evaluating any large-scale, multi-level, multi-site, program evaluation was called for. Other partnerships between systems that either directly implement interventions or are involved in the planning of intervention evaluations were viewed as necessary for helping to specify questions related to implementation system structure and process. To capture important aspects of these systems that has often been overlooked, it was highly recommended that both quantitative and qualitative measurements and analyses be used in evaluating these highly complex programs.

The evaluation specific issue areas the experts were asked to consider involved the (1) theory of change or logic models, (2) designs, (3) measurements, (4) implementation and process evaluation, and (5) analyses for MMPTs, while considering how best to implement large-scale, multi-level, multi-site evaluations and recommendation for innovations. The discussions focused on those five topical areas, however other more global and practical considerations also emerged. Thus the report is organized in seven sections, including this introductory section and the section on overarching issues. Each section is preceded by thought questions that were provided to participants prior to the meetings as well as the following general questions. At the beginning of each section is a short summary of issues that seemed to have consensus as to their importance across multiple meetings. It is hoped that the materials that emerged from this meeting will be viewed as a tool to the field.

II - Overarching issues

Prior to the meetings, participants were asked to consider this general question:

- What are the critical issues to consider in designing, implementing and evaluating complex, large scale, multi-level (Federal, State and local levels), multi-site, health promotion/prevention models for the delivery of coordinated evidence-based programs (EBPs) at the community level in order to demonstrate change in core substance use and other mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) outcomes?

The overarching issues that emerged fell into three areas:

- Definition of an MMPT

- Federal, State and local characteristics that should be considered in an MMPT evaluation

- General consideration for an MMPT evaluation

- Definition of Multi-level, Multi-site, Prevention Trials (MMPTs)

- MMPTs include at least two levels of implementation (e.g., Federal and local, State and local) in multiple sites where evidence-based prevention practices are employed. MMPTs should be based on:

- assessed need and resources of the community/local level,

- strategic plan based on the community assessment,

- a theory of change and associated logic model, and

- developmentally appropriate evidence-based interventions (EBIs) that address the assessed needs and have demonstrated the ability to produce measureable outcomes concomitant with the logic model.

- MMPTs include at least two levels of implementation (e.g., Federal and local, State and local) in multiple sites where evidence-based prevention practices are employed. MMPTs should be based on:

- Characteristics of federal, state and local components of MMPTs that should be considered in evaluations

- Federal Level

- Multi-agency federally funded MMPTs may have two or more federal partners with defined roles

- Multi-agency federally funded MMPTs may have unified application and review processes across cooperating federal agencies

- Multi-agency federally funded MMPTs may have standardized reporting measures across cooperating federal agencies

- Relationships and roles between multi-agency federally funded MMPTs and States may be specified

- Relationships and roles between multi-agency federally funded MMPTs and communities may be specified

- Characteristics of federal multi-agency MMPTs funding programs should be a strong focus of the evaluations

- State Level

- Collaboration and coordination across state agencies may be integral to the success of MMPT’s that address substance use and associated MEB problems among children and adolescents

- Characteristics of the collaboration and coordination across State agencies involved in joint funding of an MMPT should be a strong focus of the evaluation.

- The nature and quality of interagency collaborations may vary across States

- Collaborative roles and efforts may differ by agencies across States and over time

- States may vary in the degree to which they establish data sharing agreements and capacities

- Capacity and resources for new data collection may vary by State and within States at the agency level

- Capacity and resources for technical assistance on data evaluation may vary by State and within States at the agency level

- Capacity and resources for technical assistance for selection and implementation of EBPs may vary by State and within States at the agency level

- Local Community Level

- Selection of EBPs should be based on community-level risk assessments, resources and needs

- Target populations may vary in demographic characteristics across communities (e.g., problems addressed, age, context)

- The nature of the EBPs selected for implementation may have different features across communities, such as:

- “Component” interventions consisting of individual evidenced-based programs (EBPs) or strategies

- “Packages” of interventions consisting of groups of EBPs and strategies; as called comprehensive prevention programming

- Structural and functional interventions for changing institutional structures, systems, environments, procedures, or policies

- Selected programming may vary across individual neighborhoods, communities or other local areas

- Capacity for implementation of specific interventions may vary within and across communities

- Capacity, skills and resources for community-level evaluation elements may vary across communities

- Federal Level

- General aspects of MMPTs

- Theories of change that guide an MMPT should reflect how change is expected to occur within a level and across the multiple levels

- Theories of change and associated logic models should incorporate knowledge about how systems are known to or are expected to operate.

- A developmental focus needs to be included.

- An advisory group of scientists and practitioners can be very helpful to an MMPT in designing its structure and function, including the evaluation (e.g., designing the assessment of resources and risks, the local options for programming and evaluation, developing and vetting questions, and keeping the evaluation on track)

- Background information is needed to inform definitions for components of MMPTs including their internal and external operations (e.g., How do State agencies create and implement technical assistance structures and programs for supporting communities? Are there consistent sequences/steps/elements States can use in facilitating community level implementation? How useful are Federal level data systems and analyses for community level planning?)

- Communities generally need on-going technical assistance to develop capacities for conducting needs assessments, implementing EBPs, and measuring and analyzing program impacts (e.g. data systems to identify problems, track programmatic progress and modify efforts for continuous quality improvement (CQI), and measurement batteries that change over time to identify long-term outcomes).

- Evaluations of MMPTs are strengthened by using the same measures across all sites.

- Federal and State level centralized data collection and monitoring systems need to be maintained, augmented or developed and platforms need to be created to provide resources for community assessment, measurement and reporting, including tracking short and long-term youth outcomes.

- Subgroups defined by culture and language should be included in an evaluation as much as possible and the extent to which they are missing from measurement should be considered in both decision-making and reporting results of analyses.

- Large rural states present unique evaluation challenges, for example “community” may include large regional structures that provide resources and services to relatively remote areas at an economy of scale that makes sense given long distances between settled areas and variability in population density.

III - Logic Models or Theories of Change:

Prior to the meetings, participants were asked to consider the following question:

- What are the standard or most common approaches for selecting proximal and distal outcomes within logic model?

Points of Consensus

- The complexity of MMPTs calls for the development of a logic model for each of the multi-levels and for the interactions between the levels

- Communities may need TA to develop a logic model for the local level which can guide both the selection and quality implementation of evidence based interventions (EBIs) and the evaluation of the comprehensive community programming

- Definitions of Theory and Logic Model:

- Theory:

- Many theories (e.g., learning theory, social cognitive theory, identity theory, family systems theory, health beliefs model, etc.) are used in prevention to predict health behavior changes.

- Theories are system of ideas intended to explain behavior. In developmental theories the emphasis is on age-related changes in behavior from birth to death with attention to the causes of such changes.

- Change is often observed during periods of transition such as biological transitions (e.g., puberty), normative transitions (e.g., moving from elementary to middle-school), social transitions (e.g., dating) or traumatic transitions (e.g., parental divorce), as these are points of vulnerability.

- Theories identify factors that are associated with and presumed to contribute to single or co-occurring outcomes such as the onset of substance use, delinquency, high risk sexual activity, etc.

- Many theories point to individual, family and other social factors that are malleable; these malleable factors are often the focus of the intervention (s). These factors are organized within a conceptual and temporal framework.

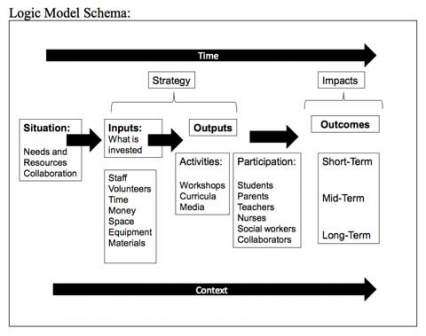

- Theory of Change or Logic Model:

- There are numerous definitions for logic model; however they all convey the same general idea. That is, a logic model illustrates conceptually and visually, in a step-by-step fashion, how an intervention will be implemented, the basis for the evaluation, and both the short-term and long-term expected outcomes.

- Logic models address specified needs and contain inputs (what is invested), outputs (activities and participation) and outcomes (short-, medium- and long-term or proximal and distal).

- Most logic models are guided by theoretical assumptions, called a theory of change that directs what is placed in the logic model and where it is placed.

- A well defined logic model will make strong, measurable connections between strategy and desired impact.

- Theory:

- General Logic Model, Theory of Change issues:

- MMPTs are complex. This complexity makes it necessary to have a clearly defined theory of change or logic model for both program planning and evaluation purposes.

- The proposed NPS and PPC program are complex multi-level, multi-site operating systems for implementing EBIs. There needs to be an a priori logic model for how they are expected to operate at each level and across levels.

- The local level programming should involve the community advisory board (CAB) in building the logic model to insure it reflects the primary community needs.

- A clearly defined logic model is needed for both the design of a large-scale MMPT and for its evaluation.

- The logic model should tell the story of how program implementation (input) addresses the assessed needs and targeted outcomes that are addressed in the evaluation.

- The logic model shows the flow of the input/outputs to the outcomes.

- The theory of change/logic model explains the temporal order of changes that are expected to lead to the short-, mid- and long- term targeted outcomes as well as the connections between program activities and outcomes that occur along the way. The proposed outcomes should consider associations between substance abuse prevalence, risk and protective factors and EBI outcomes.

- The evaluation should specify how the logic model will be measured over time and include measures at all of the multiple levels including measure of structure, process and performance

- To have more confidence that the logic model will work as explicated, it could be based on the logic models of other multi-state randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (e.g., PROSPER, CTC) that have demonstrated measurable population-based reductions in problems such as substance use, inconsistent parenting, lack of parent monitoring and family conflict. Thus, logic models should illustrate in detail the potential to reduce substance abuse and mental health and substance abuse and other targeted MEB problems.

- With both intervention and system change evaluations, the final conclusion often relates to whether it worked, rather than why or how. To determine the why and how of an intervention’s success, the logic model should reference to empirical findings regarding for whom and under what conditions components of a comprehensive community prevention were successful.

- To ensure the logic model is working as proposed, data collection should yield information in time (e.g., 6 months to a year) to take corrective action if necessary and provide continuous quality improvement.

IV - Evaluation Design:

Prior to the meetings, participants were asked to consider these questions:

- What is the range of designs that can be used to examine the effectiveness of complex, large-scale, multi-level, multi-site prevention models targeting proximal, intermediate and long-term MEB outcomes in youth (aged 9-25)?

- What are the strengths and limitations of each design?

- How can the designs be used to make comparisons between States and communities?

Points of Consensus

- The evaluation design is, to a large extent, dictated by the logic model.

- Logic model and evaluation design together determine the appropriate measures.

- A mixture of evaluation design models, including both qualitative and quantitative methods, may be the best approach to addressing the variety of goals and outcomes of an MMPT

- The evaluation design for an MMPT should incorporate a comparison group or a strong approach to measuring change in one group over time (e.g., multiple base lines

- RCTs remain the strongest evaluation design for interventions and MMPTs

- Sometimes true RCTs are not feasible for MMPT evaluations; however, there are elements of randomness that can be used to strengthen a robust quasi-experimental design.

- The evaluation design should include longitudinal tracking of units of analysis to allow for observation and assessment of trends and changes related to the primary questions of interest

- The best evaluation designs balance internal and external validity; designs should consider generalizability to real world settings.

- Even though EBIs have been well tested, and some issues around implementation process have been determined (e.g., human resource needs, space needs, timing, specific activities), implementation should still be a focus of an MMPT evaluation design as the implementation resources, strategies and practices within and across the multiple levels need to be explicated

- Evaluation designs should address how the largest units of analysis (e.g., regions of the country, States, regions of states, counties) differ in terms of demographics (e.g., geography, population density, weather) and resources (e.g., money, staff and services (e.g., staff training, client transportation).

- Classes of quantitative research methods:

- A cross-sectional study is a descriptive study in which the status of the study populations on measures or questions of interest are assessed at the same time. These assessments give a "snapshot" of characteristics of that population at a particular point in time.

- These data can be used to assess the prevalence of factors or conditions in a population; however, it is not possible to distinguish timing of events and cause and effect relationships.

- A longitudinal study involves repeated measures of the same subjects using the same questions/items over a period of time.

- In an implementation study where two or more groups (with at least one receiving the intervention and the other not receiving it) are compared, changes can be tied to the effects of the intervention.

- Even without implementation of an intervention condition, the repeated observation of individual subjects over time results in longitudinal studies having more power to detect ‘true’ change than cross-sectional studies

- A cross-sectional study is a descriptive study in which the status of the study populations on measures or questions of interest are assessed at the same time. These assessments give a "snapshot" of characteristics of that population at a particular point in time.

- Design types

- There are 3 major study design appropriate for MMPTs:

- RCTs – randomized controlled trials

- Quasi-experiments

- Non-experimental designs

- Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) is a study design that randomly assigns subjects to intervention or control group(s). Through random assignment it is assumed that both groups are equivalent on important measures and that post-test differences are due to the intervention.

- Measures members of each group before and after the intervention takes place on key variable (e.g., demographic, personal characteristic, environmental characteristic and resources)

- Looks at the impact of the intervention by measuring changes on outcome measure

- Quasi-experimental designs refer to a broad range of experimental designs that are nonrandomized, pre-post intervention studies; these designs are often used when it is not feasible or ethical to conduct an RCT. These designs select and assign groups based on similarity of key characteristics, through non-random methods

- Matching characteristics could include: family demographics (e.g., socio-economic status, parent education), child personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, grade in school), or environmental characteristics (e.g., geographic location, population denisity)

- Statistical analyses are often used to control for differences in groups that could not be accounted for simply by matching

- Members of each group are measured on key variables before and after the intervention takes place

- Analyses look at the impact of the intervention by measuring changes on outcome measure

- A generic control group design uses general population measures from existing survey samples (e.g., the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), the Monitoring the Future Survey (MTF), the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)) to assess changes in the group receiving intervention

- Examples of quasi-experimental evaluation designs:

- Matched samples design uses two samples in which an individual in one sample is matched with an individual in the other sample so that the two individuals (and thus the samples) are equivalent (or nearly equivalent) with respect to a specific variable that the researcher would like to control.

- Time series or interrupted series is an evaluation design in which a single population group is studied over a period during which several measurements are collected to establish a baseline after which an intervention takes place (i.e., change in policy, media intervention). Following the intervention more measurements are collected to determine its effect on outcomes of interest.

- The power of a Time Series design can be augmented through nesting cohorts

- Random, staggered roll-out, or delayed implementation of a program or policy is a method used to create a comparison group through postponing intervention for some portion of the study population for a designated period of time.

- This method is used to more easily manage the implementation of the intervention and to build in a control condition.

- For example, 30 states are selected to receive an intervention; by lottery one-third of the States are selected to begin the intervention in each year for three years. Thus, in year 1, 10 States are the intervention group and 20 are the control group, in year 2, 20 are in the intervention group and 10 in the control; in year 3 all states receive the intervention.

- Regression discontinuity (RD) designs are a set of design variations of pre-post-group comparisons whereby subjects are assigned to conditions (intervention or comparison groups) solely on the basis of a cutoff score on a pre-program measure. These designs are appropriate when the objective is to target a program or condition to those who need it the most. Unlike randomized or quasi-experimental designs, RD design does not require the assignment of potentially high risk individuals to a no-program comparison group in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the program.

- Non-experimental designs do not use a comparison group and are therefore the weakest in measuring the impact of the intervention. These designs assume full coverage of the target population (e.g., a media campaign)

- The time series design is the strongest non-experimental. It takes multiple measures before and after the intervention is implemented and compares trends in the outcome variables over time. Time series is a good design choice for population level interventions such as policy implementations.

- There are 3 major study design appropriate for MMPTs:

- Design Considerations:

- Selection of a particular design may depend on factors such as:

- The provision/non-provision of the intervention to specific populations

- The ability of the design to capture ‘real world’ processes and change (external validity)

- Randomness can add power to an evaluation design

- Random assignment is used to assign the sample to different groups or interventions

- Random selection is a sampling method that draws the sample for a study from the population of people eligible for the study

- It is possible to have both random selection and assignment in the same study (e.g., a random sample of 50 communities was drawn from a population of 300 that meet minimum criteria current (random sampling); then 25 communities were randomly assigned to receive the program and the remaining 25 were controls (random assignment)

- Reasons for having one or more comparison groups:

- Other programs in the community may account, wholly or in part, for measured changes

- Other national, regional or local events may account, wholly or in part, for the changes (e.g., the major employer closes, a natural disaster (hurricane, tornado) occurs

- Growth and development of the target population may account, wholly or in part, for measured changes (e.g., as children transition from elementary to middle school and from middle-school to high school, rates of substance use initiation generally increase)

- Self-selection into the intervention by those who are most likely to be successful may account, wholly or in part, for measured changes (e.g., good parents who want to hone their parenting skills)

- Factors that differentiate designs:

- Use of a comparison group(s)

- Selection and assignment of participants to groups or conditions

- When and how often data are collected

- The complexity of the data analytic plan

- Reductions in problem behaviors or increases in health promotion behaviors are assumed to be due to the implementation of the intervention.

- A rigorous evaluation design should include measures appropriate for assessing

- The short-, mid- and long-term outcome foci of the MMPT

- The logic model/theory of action

- The processes related to the formations and functioning of collaborations including coordination within and across participating partners (e.g., federal, state, and local agencies, NGOs, businesses, coalitions, etc.)

- Implementation questions (e.g., measuring adoption, delivery, exposure, engagement)

- Effectiveness questions (e.g., for selected components of individual EBP and packages of EBPs; within/across communities)

- The measures necessary to meet Federal and State reporting requirements

- Selection of a particular design may depend on factors such as:

- Existing Evaluation Models

- There are a number of MMPTs with strong evaluation designs:

- The overall evaluation model for the Strategic Prevention Framework – State Incentive Grants (SPF-SIG), data for this evaluation are located at the National Addiction & HIV Data Archive Program (NAHDAP)

- The evaluation plan for the Washington State SPF-SIG used elements of randomness in its evaluation design

- Communities that Care (CTC)

- Promoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER)

- Multi-Dimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC)

- The Norwegian effectiveness Study of Parent Management Training – Oregon model (PMTO)

- There are a number of MMPTs with strong evaluation designs:

V - Measurement Discussion

Prior to the meetings, participants were asked to consider these general questions:

- What are issues to consider in operationalizing key components (e.g., community, collaboration) in large scale multi-level, multi-site implementation models?

- What information can be helpful to understanding how defined qualities of community (e.g., boundaries of the community; location [rural/urban]; demographic characteristics; population size; size of target population; existing prevention infrastructure) can affect outcomes?

- What existing data systems (Federal, State, local) can provide essential information about process and outcomes of complex, large scale, multi-level prevention models? What other data systems would be ideal for documenting implementation process and outcomes (e.g., created coordinated at Federal/State/local levels, augmented, harmonized)?

- What are issues to consider for establishing core evaluation outcomes such as core process and community outcomes, and perhaps individual outcomes—to be collected across all communities?

- What are measurement issues to consider in demonstrating the impact of an infrastructure that augments prevention capacity at the State level and funds communities with prevention experience, on community level changes (e.g., change in community climate/environment that are linked to MEB outcomes?

Points of Consensus

- The theory of action precedes measurement. That is, there should be measures to address all aspect of the theory of action/logic model

- If theory and measurement are good, data can be re-analyzed to address additional questions over time

- Complex research involving MMPTs requires attention to the level of measurement to ensure that the measures are appropriate for the planned analytic strategy

- There is a critical need for national data platforms that collect, consolidate, store, analyze and disseminate data on children and youth

- Data stored in a national platform should be available to States and local areas for use in needs assessments, evaluations and other legitimate purposes

- Mechanism for timely data feedback to local areas should be institutionalized in order to provide CQI.

- MMPT evaluations are enhanced when measures are the same across sites

- Measures should be repeated and consistent over time

- Key Measurement Issues for MMPTs

- The definition of local area/community should be specified by the MMPT. Characteristics worth considering include:

- Community demographics (e.g., populations size, land area, community resources)

- Demographics of the population (e.g., age, ethnic/cultural diversity, poverty level)

- Community context (e.g., rural, suburban-rural (commuter), suburban-metro, small city, large urban (neighborhoods)

- Density and homogeneity/heterogeneity of the population

- Community prevention context:

- Communities often have a variety of unrelated prevention interventions being offered that target the same or overlapping outcome; the evaluation should assess the contribution of all interventions to the target outcomes

- The processes underlying a community’s ability to establish and maintain a prevention collaboration must be measured

- The reach of the MMPT components into the community must be documented in order to accurately assess outcomes

- The resources and prevention structure of a community can impact quality of implementation of an MMPT, thus they must be measured

- Data collection can be a burden to communities

- Data that is fed back to communities quickly can be used for Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)

- (e.g., Pennsylvania is establishing a meta-system for communities)

- Centralized State-level collection of community data can be augmented through the use of interactive web-based tools

- Adequate measurement of local area/community characteristics can lead to the definition of meaningful ‘communities types’

- The definition of local area/community should be specified by the MMPT. Characteristics worth considering include:

- Levels of measurement:

- Individual level (e.g., emotional, cognitive, social functioning, health, culture, academic achievement)

- Family level (e.g., income level, family structure, marital status, parent monitoring skills)

- School level (e.g., truancy rates, rules enforcement, social norms around drug abuse, bullying)

- Community level (e.g., recreational resources, public services, community cohesion, built environment, policy enforcement of underage drinking and tobacco use policies)

- State level (e.g., resources for training, technical assistance, and evaluation; interagency agreements and working relationships; state education data; juvenile justice, and child welfare data; violent crime statistics)

- Federal Level (e.g., national trend data (e.g., drug abuse by age or risk behavior by gender by age); zip codes; required agency reporting measures and data ( e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Outcome Measures (SAMHSA NOMs) or implementation fidelity measures)

- Natural/ physical ecology (e.g., weather, natural resources, terrain; environmental impact including natural disasters)

- Other:

- Economic measures (e.g., cost-benefit measures; change in payment systems)

- Medical or public health measures (e.g., Quality of Adjusted Life Years)

- Potential iatrogenic effects of specific or comprehensive programs should be monitored

- Types of measures and variables:

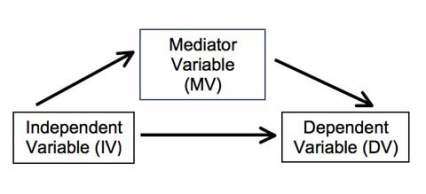

- Independent variable (IV):

- IVs variables occur before the outcome or dependent variables

- IVs are expected to affect or predict the dependent variable(s) (DVs)

- IVs are often called predictor variables

- Moderator variables are a special class of IVs

- The IV cannot be changed or easily changed (i.e., sex, race, ethnicity, poverty)

- They affect the strength or direction of an outcome

- Dependent variable (DV):

- The DV is the outcome or what is expected to change

- DVs are sometimes called outcome variables

- DVs do not affect the IV (i.e., early childhood aggression (IV) can affect adolescent drug use (DV), but adolescent drug abuse does not influence early childhood aggression)

- There can be both proximal and distal DVs or outcomes (i.e. change in community collaborations may be a proximal outcome whereas change in children’s behaviors may be a distal outcome or change in academic achievement is manifest by different milestones over time and hence different proximal and distal measures by age/developmental status)

- Proximal DVs can affect distal DVs

- Mediating variable(MV):

- MVs help to explain the relationship between the predictor variable (IV) and the outcome (DV)

- In prevention, MVs often represent the hypothesized theory of action as operationalized through the intervention (e.g., parent skills training would affect parental monitoring and subsequently adolescent alcohol use)

- Independent variable (IV):

- Implementation measures

- The quality of implementation accounts for of the majority of the variance in program outcomes; thus it is critical to:

- Document and evaluate community readiness, capacity, and collaborative relationships as this provides benchmarks for implementation process over time

- Track fidelity of implementation at all levels of the MMPT, for example:

- The timeliness and responsivity of service provided by federal grant program officials to States

- Consistency in quality of training and technical assistance provided by the State to communities

- Adherence to protocols at the community level

- Other implementation factors, including:

- State and community plans as measures of variability across setting and accomplishment within setting

- Utilization of the training, technical assistance, and coaching being offered

- Who is being reached by the programming, with what and at what dosage

- Factors that influence the development and sustainability of collaborations (e.g., financial resources, community size and layout, team functioning)

- Dosage will vary by sites at all levels of an MMPT (e.g., by federal and State agencies and by communities)

- Community plans can be a tool for assessing progress toward goals

- Measuring proximal outcomes at intervals beginning early and often in the project (e.g., 6, 9, and 12 months) provides indications of implementation quality

- Measures of the strength of the prevention partnership (e.g., community engagement, scope of efforts, sustained activities)

- The quality of implementation accounts for of the majority of the variance in program outcomes; thus it is critical to:

- Generic Outcome Comparisons

- Population-based measures can be used to provide comparisons when no comparison group is available

- Some federal data sets make data available for comparison including:

- Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)

- Monitoring the Future (MTF) data

- National Survey of Drug Use and Heath (NSDUH)

- State level data for comparisons is often available through a state’s Department of Education

- Accessing and developing core measures:

- Some federal and state agencies have core indicator measures that grantees must collect (e.g., SAMHSA NOMS)

- Standardizing these across agencies would facilitate the work of states and communities

- The National Prevention Network (NPN) Research Committee has asked for assistance in standardizing a CORE set of prevention process measures for use in aggregating program and community outcome data required for some Federal grant reporting

- Population surveys (e.g., YRBS, MTF) can be used to select some standardized measures.

- Many states have school surveys that can provide community-level estimates

- Some state agencies collect data on particular populations of children and youth (e.g., social welfare, Juvenile Justice) which could be useful if accessible.

- There are some measurement platforms available that offer menus of valid and reliable measure across domains of interests to federal and State agencies and communities (e.g., PhenX https://www.phenx.org/ NIH Toolbox https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/nih-toolbox) including cognitive and MEB outcomes

- Some federal and state agencies have core indicator measures that grantees must collect (e.g., SAMHSA NOMS)

- Examples of Existing MMPT Measurement Schemas

- The SPF-SIG evaluation created a Restricted Use Data Set that can be accessed through the National Addiction and HIV Data Archive Program (NAHDAP) located at the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Science Research (ICPSR); the web address for this resource is https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NAHDAP/studies/28921. The data set is a resource for states and communities interested in:

- Accessing measures for use in local evaluations

- Accessing data for comparison to local outcomes

- The data set includes:

- Strategic plans (e.g., coded for meeting priorities, infrastructure development, funding allocation)

- Quarterly reports (e.g., management and oversight processes)

- Implementation interviews (e.g., implementation quality, cultural competence)

- Infrastructure interviews (e.g., State organization structure, planning, workforce development)

- Community Level Instrument (e.g., implementation of the framework, expanding prevention capacity)

- State Level Instrument

- The State of Kansas monitors and documents new and modified programs, policies, or practices with an on-line Documentation Support System (ODSS). It includes:

- Process data on systems change

- Traditional outcome indicators (e.g., reductions in past 30-day alcohol use or priority risk factors or influencing factors).

- The Communities That Care (CTC) operating system provides communities with a structure that includes and evaluation component, more information is available at: https://www.communitiesthatcare.net/

- In some cases data may be collected, but difficult to access, even at the aggregate level (e.g, schools, juvenile justice, child welfare, school drop-out data)

- The SPF-SIG evaluation created a Restricted Use Data Set that can be accessed through the National Addiction and HIV Data Archive Program (NAHDAP) located at the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Science Research (ICPSR); the web address for this resource is https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NAHDAP/studies/28921. The data set is a resource for states and communities interested in:

VI - Implementation and Process Evaluation Discussion

Prior to the meetings, participants were asked to consider these general questions:

- How can factors such as Implementation process, implementation quality and success of implementation that influence the overall impact of a comprehensive prevention model be incorporated in the evaluation plan?

- At what levels of a complex, multi-level, multi-site prevention model should implementation be measured? [Federal, state and local]? Family, provider, system or community level?

- What measures exist to aid in developing these complex evaluations?

Points of Consensus

- A process evaluation is essential to understanding outcomes of an MMPT

- The strength of the evaluation is increased when the same measures are used and the same evaluation questions are asked across sites

- Implementation occurs at all levels of an MMPT; the evaluation plan should incorporate all of those levels

- Key community implementation and process evaluation issues:

- Communities often need evaluation readiness support, including the following:

- Training and technical assistance around formation of local evaluation teams

- Scientist advisory group for support with research questions and evaluation design

- Training, technical assistance and coaching for professional development toward support of evaluation taking place at the community level

- Outside evaluators need to be sensitive to local context to optimize collaboration with community teams

- Identify risk and protective factors in each community

- Recognize cultural/ geographic variation

- Improve local capacity to implement and collect data

- Identify context specific factors within each community

- Communities often need evaluation readiness support, including the following:

- Assessment of program at Federal, State and local levels:

- At the Federal level

- Coordination of application, review and reporting criteria and implementation processes across federal agencies

- Cross-agency coordination of efforts, including lead agencies and roles

- Cross-agency pooling of resources

- Qualitative difference in operations at the Federal level over time

- Links between the Federal and State government

- Structures in place to assure coordination between states and the Federal government

- Cross-agency coordination of efforts, including lead agencies and roles

- At the state level

- Infrastructures differ from state to state; how can an evaluation account for this

- Links between the State and community level

- How does coordination between state and community differ from one community to another

- From the community perspective, what is the State doing differently due to the MMPT

- What is the community’s response to the changes in infrastructure

- How does funding flow from federal, to state level and down to specific local level infrastructure and programming

- At the Federal level

- Implementation evaluation methods:

- Formative evaluation techniques may be used to improve programming on a continuing basis

- Many qualitative methods may be useful for evaluating specific aspects of MMPTs (e.g., what works in particular settings, state to state differences that contribute to outcomes); these methods include:

- Participant observation

- Field notes

- Grant application coding

- Market research

- Structured interviews

- Open ended questions

- Focus groups

- Quantitative statistical and mathematical methods are the most common and generally the easiest methods for evaluation; however, for implementation the challenge is lack of availability of valid and reliable measures

- There are some methods that are a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches, for example, case studies

- New technologies provide tools for evaluation (e.g., iPADs and PDAs can be used for data collection and tracking subjects)

- Examples of prevention Implementation models that promote evaluation:

- OSLC MTFC model for measuring implementation structure and processes through flexible stages; the framework includes:

- Time/Stage – Measures time, engagement, quality

- Feasibility – Tracks meetings, attitudes

- Readiness and planning – Includes funding; staffing; recruitment; communications plan;

- Hiring and training staff – Timing, dates

- Fidelity monitoring – Online easier

- Services – When(start date) and ongoing

- Tracking model fidelity -- Staff adherence

- Sustainability -- Web-based measure

- The PROSPER Project (PROmoting School-community-university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience; https://prosper.ppsi.iastate.edu/) has found that important aspects for assessing process and implementation include:

- Link into existing infrastructures (e.g., Cooperative Extension system, education department) with a science-to-practice orientation

- Level and structure of technical assistance (TA) in State and Federal model to integrate at the State and local levels

- Sustainability with high quality implementation within the extant infrastructure

- Unique partnership among scientists (State level), practitioners, TA, community

- OSLC MTFC model for measuring implementation structure and processes through flexible stages; the framework includes:

VII - Analysis

- Prior to the meetings, participants were asked to considerer the following questions: What are the issues to consider for determining the appropriate units of analysis for complex, large scale, multi-level prevention models implemented in multiple communities?

- With a relatively small number of communities participating and a prevention program that targets multiple age groups and outcomes, how can subgroup analyses be conducted to capture within group and between group differences?

Points of consensus:

- Measurement precedes analysis; to be able to conduct comprehensive MMPT evaluation analyses, appropriate measures at the appropriate levels of the MMPT must be operationalized and collected.

- Adequate attention to theory, logic model development and measurement is critical to the success of analyses as statistical applications cannot correct for inadequacy in those areas

- Analysis issues:

- Development of the data analysis plans is an integral and critical piece of the project design

- The complexities involved in an MMPT evaluation require specialized expertise in methodological, statistical and data analysis design

- There are many methods of analysis with relevance for MMPT data or portions of the data

- MMPTs may need multiple data analyses

- For outcomes at different levels

- For different categories of outcomes (e.g., process vs. outcome)

- For the project as a whole and for specific areas of interest at the various levels, especially the community level

- For different sites

- Statistical power is a major issue and must be addressed

- Standardized instruments are hard to apply locally but should be incorporated, even if the interventions are not all the same

- Effect sizes reporting issues; how big a difference is needed

- If between-group differences are not found, how would that be interpreted

- The variables for subgroup analyses need to be specified in advance

- Mixed methods can produce mixed results

- Ethnographic assessments may be helpful in detecting problems that can be corrected

- Real outcomes are latent outcomes, not immediate, taking a minimum of 3 years; hence, the importance of measuring proximal outcomes

- Also, the potential for finding iatrogenic effects is there; and, when found, requires necessary changes to the program to address them.

- Missing data

- Methods of Analysis

- Many types of analyses are appropriate for use within an MMPT evaluation framework

- Given the scale of an MMPT multiple types of analyses will be needed to answer proposed process and outcome questions

- Some analytic techniques to consider are:

- Propensity score analysis

- Network analysis across agencies and timePattern-matching analyses

- Time-series analyses for scale-up efforts

- Regression-discontinuity analysis

- Analysis of changing attitudes and practices across the community

- Subgroup analysis within the population

VIII - Summary

The evaluation of large-scale, multilevel, multisite, health promotion/prevention trials requires advanced planning, specificity in regard to the program components and evaluation design, and the underpinning of research-based models. In wide-ranging discussions, meeting participants raised the following as critical elements in the evaluation planning and implementation process:

- Evaluations should consider the outcomes and findings associated with evaluations of past partnerships and coalitions, such as the SPF-SIG, Safe School Healthy Students SSHS) and Drug Free Communities (DFC) to determine how existing designs, measures, and methods can be applied to an MMPT evaluation

- Assistance in evaluation design and development in terms of

- An advisory group for developing questions and keeping track of evaluation milestones

- Technical assistance to the community on evaluation design and infrastructure development

- Efforts to include rigorous design involving randomization if possible

- Specification of logic models built on prevention intervention research and evidence-based models, like the SPF-SIG

- Development of core measures and centralized data reporting system to allow for cross-site comparisons

- Clear specification of evaluation questions and measurements needed to answer questions

- Specification of the structure, process, and measurement of the program and implementation system at all levels

- Evaluation design with both quantitative and qualitative measurements and analyses to report on outcomes and help explain how those findings came about, what happened and to whom

IX - List of Resources

Communities That Care (CTC)

Oesterle S, Hawkins JD, Fagan AA, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Testing the universality of the effects of the Communities That Care prevention system for preventing adolescent drug use and delinquency. Prev Sci. 2010 Dec;11(4):411-23. Erratum in: Prev Sci. 2010 Dec; 11(4):424.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report: Preventing Mental, Emotional and Behavioral Disorders among Young People (2009), provides background on targeted risk and protective factors and evidenced-based programs (EBPs) that address them, https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12480/preventing-mental-emotional-and-behavioral-disorders-among-young-people-progress

Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC), Preventing Behavior and Health problems for Foster Teens, http://www.oslc.org/projects

Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, Landsverk J. Mixed Method Designs in Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2010 Oct 22. [Epub ahead of print]

2010 National Drug Control Strategy. Office of National Drug Control Policy. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/ondcp/national-drug-control-strategy-introduction

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009) Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Mary Ellen O’Connell, Thomas Boat, and Kenneth Warner, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Parent Management Training – Oregon Model

Forgatch, M.S., & DeGarmo, D.S. Sustaining Fidelity Following the Nationwide PMTO™ Implementation in Norway. Prev Sci, 2011, 12:235–246

Promise Neighborhoods – https://promiseneighborhoods.ed.gov/

PROSPER Articles, https://prosper.ppsi.iastate.edu/

Perkins DF, Feinberg ME, Greenberg MT, Johnson LE, Chilenski SM, Mincemoyer CC, Spoth RL. Team factors that predict to sustainability indicators for community-based prevention teams. The Pennsylvania State University, United States. Eval Program Plann. 2010 Nov 10. [Epub ahead of print]

Redmond C, Spoth RL, Shin C, Schainker LM, Greenberg MT, Feinberg M.Long-term protective factor outcomes of evidence-based interventions implemented by community teams through a community-university partnership. J Prim Prev. 2009 Sep; 30(5):513-30. Epub 2009 Aug 11.

SPF-SIG Cross-Site Evaluation -- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/SPF-SIG-Cross-Site-Evaluation-(-Cohorts-1-and-2-)-Stein-Seroussi/3bd34ff7484d2afeac244c67813d83c75ab4dcb3

Additional Information

In July and August of 2010, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) convened four meetings on the state of the knowledge regarding the evaluation of large scale multi-level, multi-site prevention interventions.

The following were the titles for each meeting:

- Perspectives from Researchers – July 23, 2010

- Perspectives from Large-Scale Evaluators – July 29, 2010*

- Perspectives from Cross-State Evaluators – August 2, 2010

- Perspectives from Program Officials with Large Data Bases – August 6, 2010

*For the purpose of these four meetings, Researchers was defined as one who was funded to conduct a controlled trial (e.g., RCT or strong quasi-experimental design) of a theory-based prevention intervention or operating system, whereas an Evaluator was defined as one who has conducted evaluations of Federal or State funded prevention intervention programs or systems.