Could drug addiction treatment of the future be as simple as an on/off switch in the brain? A study in rats has found that stimulating a key part of the brain reduces compulsive cocaine-seeking and suggests the possibility of changing addictive behavior generally. The study, published in Nature, was conducted by scientists at the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health, and the University of California, San Francisco.

"This exciting study offers a new direction of research for the treatment of cocaine and possibly other addictions," said NIDA Director Dr. Nora D. Volkow. "We already knew, mainly from human brain imaging studies, that deficits in the prefrontal cortex are involved in drug addiction. Now that we have learned how fundamental these deficits are, we feel more confident than ever about the therapeutic promise of targeting that part of the brain."

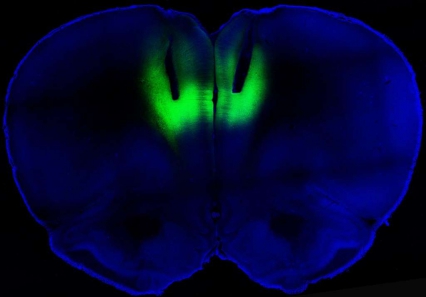

Optogenetic stimulation using laser pulses lights up the prelimbic cortex Source: Courtesy of Billy Chen and Antonello Bonci

Optogenetic stimulation using laser pulses lights up the prelimbic cortex Source: Courtesy of Billy Chen and Antonello BonciCompulsive drug-taking, despite negative health and social consequences, has been the most difficult challenge in human drug addiction. NIDA researchers used an animal model of cocaine addiction, in which some rats exhibited addictive behavior by pushing levers to get cocaine even when followed by a mild electric shock to the foot. Other rats did not exhibit addictive responses.

The NIDA scientists compared nerve cell firing patterns in both groups of rats by examining cells from the prefrontal cortex. They determined that cocaine produced greater functional brain deficits in the addicted rats. Scientists then used optogenetic techniques on both groups of rats -- essentially shining a light onto modified cells to increase or lessen activity in that part of the brain. In the addicted rats, activating the brain cells (thereby removing the deficits) reduced cocaine-seeking. In the non-addicted rats, deactivating the brain cells (thereby creating the deficits) increased compulsive cocaine seeking.

"This is the first study to show a cause-and-effect relationship between cocaine-induced brain deficits in the prefrontal cortex and compulsive cocaine-seeking," said NIDA's Dr. Billy Chen, first author of the study. "These results provide evidence for a cocaine-induced deficit within a brain region that is involved in disorders characterized by poor impulse control, including addiction."

"What I find to be an exceptional breakthrough is that our results can be immediately translated to clinical research settings with humans, and we are planning clinical trials to stimulate this brain region using non-invasive methods," said Dr. Antonello Bonci, NIDA scientific director and senior author of the study. "By targeting a specific portion of the prefrontal cortex, our hope is to reduce compulsive cocaine-seeking and craving in patients."

In 2011, there were an estimated 1.4 million Americans age 12 and older who were current (past-month) cocaine users, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. However, there are currently no medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of cocaine addiction.

The study by Chen et al. can be found at: http://www.nature.com/. For information on related research being conducted at NIDA's Intramural Research Program, go to http://irp.drugabuse.gov/Bonci.php.