Methamphetamine overdose deaths surged in an eight-year period in the United States, according to a study published today in JAMA Psychiatry. The analysis revealed rapid rises across all racial and ethnic groups, but American Indians and Alaska Natives had the highest death rates overall. The research was conducted at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health.

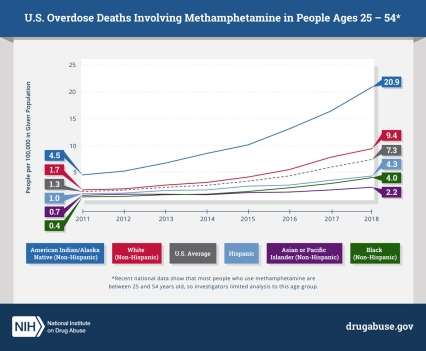

Deaths involving methamphetamines more than quadrupled among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaska Natives from 2011-2018 (from 4.5 to 20.9 per 100,000 people) overall, with sharp increases for both men (from 5.6 to 26.4 per 100,000 from 2011-2018) and women (from 3.6 to 15.6 per 100,000 from 2012-2018) in that group. The findings highlight the urgent need to develop culturally tailored, gender-specific prevention and treatment strategies for methamphetamine use disorder to meet the unique needs of those who are most vulnerable to the growing overdose crisis. Long-term decreased access to education, high rates of poverty and discrimination in the delivery of health services are among factors thought to contribute to health disparities for American Indians and Alaska Natives.

“While much attention is focused on the opioid crisis, a methamphetamine crisis has been quietly, but actively, gaining steam—particularly among American Indians and Alaska Natives, who are disproportionately affected by a number of health conditions,” said Nora D. Volkow, M.D., NIDA director and a senior author of the study. “American Indian and Alaska Native populations experience structural disadvantages but have cultural strengths that can be leveraged to prevent methamphetamine use and improve health outcomes for those living with addiction.”

Shared decision-making between patient and health care provider and a holistic approach to wellness are deeply rooted traditions among some American Indian and Alaska Native groups and exist in the Indian health care system. Traditional practices, such as talking circles, in which all members of a group can provide an uninterrupted perspective, and ceremonies, such as smudging, have been integrated into the health practices of many Tribal communities. Leveraging traditions may offer a unique and culturally resonant way to promote resilience to help prevent drug use among young people. Development and implementation of other culturally appropriate and community-based prevention; targeting youth and families with positive early intervention strategies; and provider and community education may also aid prevention efforts among this population.

The study found markedly high death rates among non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaska Natives, as well as a pattern of higher overdose death rates in men compared to women within each racial/ethnic group. However, non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women had higher rates than non-Hispanic Black, Asian, or Hispanic men during 2012-2018, underscoring the exceptionally high overdose rates in American Indian and Alaska Native populations. The results also revealed that non-Hispanic Blacks had the sharpest increases in overdose death rates during 2011-2018. This represents a worrying trend in a group that had previously experienced very low rates of methamphetamine overdose deaths.

Methamphetamine use is linked to a range of serious health risks, including overdose deaths. Unlike for opioids, there are currently no FDA-approved medications for treating methamphetamine use disorder or reversing overdoses. However, behavioral therapies such as contingency management therapy can be effective in reducing harms associated with use of the drug, and a recent clinical trial reported significant therapeutic benefits with the combination of naltrexone with bupropion in patients with methamphetamine use disorders.

NIDA investigators led by Beth Han, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., obtained data used in the analysis from the 2011-2018 Multiple Cause-of-Death records from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistics System, the nation’s most complete database of births and deaths.

Recent national data show that most people who use methamphetamine are between 25 and 54 years old, so the investigators limited their analysis to this age group. When they examined data from this population as a whole, they found a surge in overdose deaths. Deaths involving methamphetamines rose from 1.8 to 10.1 per 100,000 men, and from 0.8 to 4.5 per 100,000 women. This represents a more than five-fold increase from 2011 to 2018.

“Identifying populations that have a higher rate of methamphetamine overdose is a crucial step toward curbing the underlying methamphetamine crisis,” said Dr. Han. “By focusing on the unique needs of individuals and developing culturally tailored interventions, we can begin to move away from one-size-fits-all approaches and toward more effective, tailored interventions.”

This work was supported by The National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Han B, et al. Methamphetamine overdose deaths in the United States: Sex and racial/ethnic differences. JAMA Psychiatry DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4321 (2021).

For more information on methamphetamines, go to: NIDA’s Methamphetamine Resources