Cocaine is known to be a highly addictive drug; however, little is known about the factors that make some individuals more vulnerable to it than others. Recently, NIDA-supported researchers at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, have provided potential insight as to why some drug abusers have an increased susceptibility to cocaine addiction. They have found a link in monkeys between environmental conditions, the brain chemical dopamine, and the addictive qualities of cocaine. In the study, transferring the animals from individual to social housing produced biological changes in some animals that decreased their response to cocaine.

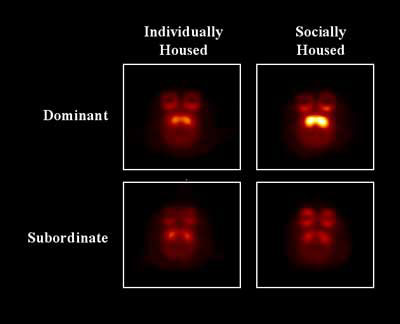

Brain Images of Monkeys Housed Individually and After Transfer to Social Housing. In these PET scans, lighter colors represent increases in markers of dopamine D2 function. Greater levels of D2 markers in socially housed, dominant monkeys -- attributed to their living in an enriched environment -- suggest that positive changes in one's environment can result in a biological protection from cocaine addiction.

Brain Images of Monkeys Housed Individually and After Transfer to Social Housing. In these PET scans, lighter colors represent increases in markers of dopamine D2 function. Greater levels of D2 markers in socially housed, dominant monkeys -- attributed to their living in an enriched environment -- suggest that positive changes in one's environment can result in a biological protection from cocaine addiction.Previous studies have indicated that certain environmental conditions -- such as living in an enriched environment with access to more resources or reduced stress -- may reduce animals' self-administration of drugs, particularly cocaine. Animal studies also have suggested that environmental conditions may affect the activity of dopamine. Specifically, these studies have indicated that animals' housing conditions and social rank can affect dopamine's ability to bind to dopamine D2 receptors and thereby initiate the cellular processes that produce feelings of pleasure and reward. Taken together, these findings inspired the Wake Forest researchers to look for a three-way link between environment, dopamine D2 receptor function, and drug self-administration.

The researchers studied 20 macaque monkeys that were first housed individually and then assigned to social groups of 4 monkeys per housing group. Social hierarchies were allowed to develop in each group, and social rank was determined by observations of aggressive and submissive behavior. "Placement of the monkeys in social groups is modeling two extremes -- socially derived stress for the most subordinate monkeys and environmental enrichment for the dominant monkeys," said Dr. Michael Nader, who led the study. "Although these variables have been studied in other animal models, in our model the stressors and environmental variables were not artificially produced in the lab. The model also allows us to study issues related to cocaine-induced changes in social behavior and the interactions of those changes with the reinforcing effects of cocaine."

Positron emission tomography (PET) was used to measure the amount and availability of dopamine D2 receptors while the monkeys were individually housed and 3 months after their placement into social groups. After the second PET scan, monkeys were trained to self-administer cocaine by pressing a lever. They were allowed access to cocaine during daily sessions; the rate of cocaine self-administration was determined by the number of times the lever was pressed.

The second PET scan revealed that the monkeys that had become dominant now had 20 percent more dopamine receptor function compared to when they were housed alone. In the subordinate monkeys, dopamine receptor function was unchanged. Although dominant monkeys did not avoid cocaine completely, they had significantly lower intakes of cocaine than subordinate monkeys.

"The increase in markers of dopamine D2 receptor function among dominant monkeys may be the result of an increase in the number of dopamine D2 receptors, a decrease in the amount of circulating dopamine competing for the receptors, or both as a consequence of becoming dominant," says Dr. Nader. "This suggests that, regardless of an individual's past, positive changes in the environment may result in a biological protection from the effects of cocaine. In other words, living in an enriched environment may enhance dopamine function and thus cause the pleasurable effects associated with cocaine use to be diminished."

The Wake Forest team's findings in monkeys have implications for understanding and possibly reducing drug abuse vulnerability in people. In people as in monkeys, drugs' effects on dopamine levels and function are a key to the motivation for abuse. There is evidence that individuals with low levels of dopamine D2 receptors have higher risk for abusing drugs. In these individuals, reduced dopamine function may produce less bountiful feelings of pleasure and reward from natural activities, making drug-induced euphoria more compelling. The new results suggest that it may be possible to identify environmental improvements that enhance individuals' dopamine D2 receptor function and thereby lower their risk for drug abuse.

"Dr. Nader's research shows that environmental experiences can increase dopamine D2 receptor levels, which in turn are associated with a decreased vulnerability to cocaine self-administration," says Dr. Cora Lee Wetherington of NIDA's Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. "This work, along with previous research regarding the role of dopamine D2 receptors in drug abuse, points to the need for additional research to identify both environmental factors that promote low dopamine D2 receptor levels and the associated vulnerability to cocaine's reinforcing effects as well as environmental factors that give rise to high levels of dopamine D2 receptors that confer resistance to cocaine's reinforcing effects. Such research could point to risk and protective factors that could be translated into better prevention and treatment interventions."

Source

- Morgan, D., et al. Social dominance in monkeys: Dopamine D2 receptors and cocaine self-administration. Nature Neuroscience 5(2):169-174, 2002. [Abstract]