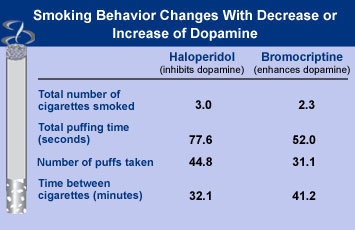

Smokers who received haloperidol, a dopamine antagonist, smoked more cigarettes during a 5-hour period and took more puffs per cigarette than did smokers who received bromocriptine, which enhances dopamine's effects.

Smokers who received haloperidol, a dopamine antagonist, smoked more cigarettes during a 5-hour period and took more puffs per cigarette than did smokers who received bromocriptine, which enhances dopamine's effects.Nicotine triggers the release of dopamine in the brain, and the pleasurable sensations that result are thought to be a driving force in establishing addiction. Animal studies, in which brain cells can be carefully analyzed after nicotine administration, confirm the link between dopamine and addictive behavior. This study demonstrates that in humans, an individual's smoking behavior can be manipulated by stimulating or blocking dopamine release.

Dr. Nicholas Caskey and his colleagues at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) and the Veterans Affairs West Los Angeles Healthcare Center monitored the smoking behavior of heavy smokers who received oral doses of either haloperidol or bromocriptine.

"Our study was designed to use these compounds to decrease or increase availability of dopamine in a single group of otherwise healthy smokers and evaluate the effect on smoking behavior," explains Dr. Caskey.

Haloperidol is used to treat some psychiatric disorders, and earlier studies found that patients with schizophrenia smoked more during treatment with haloperidol than when they were not taking the antipsychotic medication. Other studies have shown decreased smoking and craving for nicotine among smokers who received bromocriptine (used to treat Parkinson's disease and disorders of the pituitary gland).

Participants in the study (14 men, 6 women, average age 30 years) smoked 15 or more cigarettes per day for at least 2 years. On average, they had been smoking more than 12 years and smoked 20 cigarettes per day at the time of the study. All participants received both haloperidol and bromocriptine over the course of the study, which consisted of two 5-hour sessions spaced roughly a week apart. In their first session, the participants received an oral dose of either 2.0 mg haloperidol or 2.5 mg bromocriptine; in their second session, the participants received the other drug. Over the next 5 hours, the participants were allowed to smoke their preferred brand of cigarettes at will, using a cigarette holder linked to a device that measured characteristics of each puff. They also answered questions about craving and discomfort.

With haloperidol, participants smoked more cigarettes (in total, three cigarettes) per session and smoked them faster (44.8 total puffs, or roughly 15 puffs per cigarette) than they did with bromocriptine (2.3 cigarettes, with 13.5 puffs per cigarette). Participants also reported greater craving with haloperidol (4.5 on a 1-7 scale) than with bromocriptine (3.8). "These results show that smoking behavior can be manipulated within the same subjects by alternately blocking and stimulating dopamine and indicates the importance of dopamine in smoking," Dr. Caskey says.

There currently are no human trials investigating the effectiveness of bromocriptine treatment as part of smoking cessation therapy, but NIDA-supported investigations of selegiline, another medication that acts on the dopamine system, are under way. "There are very few studies that look at the effect of dopamine on smoking in subjects who don't also suffer psychiatric disorders," observes Dr. Allison Chausmer of NIDA's Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. "The findings in this study, particularly the results seen for bromocriptine, offer additional support for investigating potential medications that help control smoking by acting on the dopamine system."

Source

- Caskey, N.H., et al. Modulating tobacco smoking rates by dopaminergic stimulation and blockade. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 4(3):259-266, 2002.