NIDA, joined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), sponsored a symposium on drug discovery, development, and delivery as part of the 2003 Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. More than 300 researchers, treatment providers, and policymakers attended the 1-day meeting on February 9 in New Orleans. The symposium featured discussions of current efforts to discover new targets for potential medications, the development of medications based on existing knowledge of nicotine's effects in the brain, and factors that might speed the delivery of new treatments to smokers who want to quit.

During the discovery section of the program, speakers discussed recent findings in nicotine receptor biology and the role of neurotransmitters, such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate, in nicotine's effects on the brain. The presentations on medication development provided a background on the drug development process; emerging medications, such as antidepressants and nicotine vaccines; and an overview of medications now in development. The delivery portion of the symposium focused on strategies to create widespread medication access and use by individual smokers and within the health care system.

Discovery

Dr. William Corrigall, director of NIDA's Nicotine and Tobacco Addiction Program and symposium moderator, described the neurobiological targets of current research: genes and gene products that play a role in the structure and response of nicotinic receptors and in brain signaling pathways that involve the neurotransmitters dopamine, GABA, serotonin, and glutamate. Dr. Caryn Lerman, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, further explored the genetic factor in nicotine research, describing studies on the effect of genetic variations on the activity of enzymes that metabolize nicotine (see "Genetic Variation May Increase Nicotine Craving and Smoking Relapse.")

Dr. Marina Picciotto, of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, discussed research that has expanded our understanding of the role of nicotine receptors--the sites at which nicotine attaches to brain cells. This portion of the program also featured discussions of the possibility that neurotransmitters other than dopamine might represent new avenues for pharmacotherapy. For example, Dr. Julie Staley, also of Yale University, described current investigations into the treatment possibilities represented by medications known to act on the serotonin system. The GABA neurotransmitter system, which normally acts to limit dopamine's effect in the brain's pleasure center, might also help in smoking cessation treatment, according to Dr. George McGehee of the University of Chicago. He discussed the mechanism by which nicotine simultaneously stimulates dopamine release and depresses the effect of GABA.

Development

Dr. Frank Vocci, director of NIDA's Division of Treatment Research and Development, described the steps involved in the development of new medications and their approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)--a process that may require a decade of research and testing, at a cost as high as $500 million per medication. Accelerating the process at any stage, from basic research to human clinical trials, will speed the availability of new treatments. Dr. John Hughes, of the University of Vermont in Burlington, suggested that psychiatric medications already approved for treating neurochemical imbalances in the brain might hold clues for developing medications to treat the neurochemical effects of smoking.

Dr. Charles Grudzinskas, of Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C., summarized potential medications now in FDA Phase I, II, or III trials. These medications include additional nicotine replacement therapies and nicotine vaccines. Dr. Paul Pentel of the Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, described progress in the development of one type of nicotine vaccine--antibodies that bind to nicotine in the blood, preventing it from crossing the blood-brain barrier and reaching the areas of the brain that underlie addiction. Vaccines may be particularly effective as relapse-prevention medications for smokers who are trying to remain abstinent.

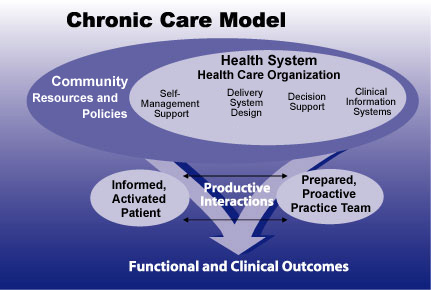

At the 2003 meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Dr. Susan Curry discussed use of a chronic care model to improve the delivery, utilization, and effectiveness of tobacco cessation treatment. This approach draws on the community--of which the health system is a part--to help patients and their practitioners effectively work toward desired health goals.

At the 2003 meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Dr. Susan Curry discussed use of a chronic care model to improve the delivery, utilization, and effectiveness of tobacco cessation treatment. This approach draws on the community--of which the health system is a part--to help patients and their practitioners effectively work toward desired health goals.Delivery

Dr. Scott Leischow, chief of NCI's Tobacco Control Research Branch, discussed barriers to delivery and utilization of current tobacco cessation treatments. These include the high relapse rate associated with current treatments and the cost and "hassle" factor that deter patients from using nicotine replacement therapy, which they contrast to the simplicity of nicotine delivery by cigarettes. To address barriers to use, Dr. Saul Shiffman of the University of Pittsburgh discussed strategies that might increase utilization of existing treatments, including regulatory changes that make cigarettes more expensive and increased advertising and education to encourage more smokers to try to quit.

Providers and insurers also need to address barriers within their control, noted several speakers. Dr. Richard Hurt, of the Mayo Clinic's Nicotine Dependence Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, discussed the limitations of current clinical treatment. He noted that relatively few medications are available, clinicians are not familiar with them, and patients are reluctant to begin treatment because of embarrassment, inadequate relief from withdrawal, and the difficulty of complying with instructions for use of gum, inhalers, or nasal sprays. Dr. Susan Curry of the University of Illinois at Chicago suggested steps that insurers and health care organizations could take to improve the delivery, utilization, and effectiveness of treatment. For example, she said, health care systems should adopt a chronic disease model to treat smoking, and insurers should include the cost of medications in coverage that provides comprehensive pharmacological and behavioral treatment.

In concluding remarks, Dr. Corrigall noted that the enthusiastic response to the day-long discussion illustrates broad support for steps that will increase and accelerate available treatment options for smokers. "Clinicians and patients need better treatment options, and this symposium represents a significant first step in a collaboration that can help speed the process of getting new and more effective medications to smokers who want to quit."