NIDA's Division of Clinical Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (DCNBR) identifies, validates, and explores the clinical implications of basic science discoveries. Much of the Division's work consists of replicating results obtained in laboratory and animal studies in human subjects. A DCNBR project typically culminates in one of two outcomes: carrying a new discovery forward for development into actual interventions or referring it back to basic scientists for further investigation.

"We are uniquely positioned to uncover the factors in humans—neurobiologic, genetic, social-behavioral—that help explain the development and effects of drug abuse," says Director Dr. Joseph Frascella. "Being positioned between NIDA's basic research division and other more applied programs, our research programs inform basic science and promote the development and implementation of new medications and behavioral treatments across NIDA."

For example, building on basic research that linked nicotine acetylcholine receptors to the regulation of attention, DCNBR-sponsored researcher David Gilbert and colleagues at Southern Illinois University demonstrated that nicotine exposure and smoking cessation both influence the ability to pay attention. Now, NIDA's Division of Pharmacotherapies and Medical Consequences of Drug Abuse is exploring the clinical impact of these observations. They are testing whether bupropion and nicotine patches affect attention during smoking cessation, and whether such effects correlate with success in quitting.

In another DCNBR-supported study, Dr. Robert Risinger and colleagues at the Medical College of Wisconsin documented a pattern of fluctuating activation of the mesolimbic reward system as six cocaine-abusing men transitioned through cycles of cocaine craving, self-administration, and highs. The results, obtained with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), confirmed previous research linking those brain areas to drug self-administration in animals, and extended them by correlating them with drug abusers' subjective feelings and responses. (see "Cocaine Craving Activates Brain Reward Structures; Cocaine 'High' Dampens Them").

Neuroimaging studies comprise onethird of the Division's research portfolio. "Brain imaging has pushed drug abuse research in the last 15 to 20 years—allowing us to directly observe neural activity of awake and functioning people and obtain specific measures on how drugs affect the brain," Dr. Frascella says. Imaging studies indicate that the human brain undergoes major changes as a consequence of drug exposure and that the adolescent brain may be particularly pliant, "which may help explain why adolescence is the period when most new cases of drug addiction occur," Dr. Frascella adds. "Thus, we've become increasingly committed to using brain imaging to get a sharper picture of how the brain changes with development and in response to active and passive exposure to drugs of abuse."

Three Branches of Clinical Research

DCNBR, formed in May 2004, has three Branches:

Clinical Neuroscience

Under Dr. Steven Grant's leadership, the Clinical Neuroscience Branch focuses on how drug abuse affects the human central nervous system, including brain changes during different stages and states of abuse, such as addiction, withdrawal, abstinence, craving, and relapse. It also studies:

- The factors that make some individuals more vulnerable and others more resilient to drug abuse and addiction;

- The impact of drugs on learning, memory, judgment, and decision-making;

- Co-occurrence of drug addiction with other mental disorders;

- Neurobiological changes that result from behavioral and pharmacological treatments for drug abuse; and

- Interventions to ameliorate the negative health consequences of drugs, whether self-administered or incurred prenatally.

As an example of a recent Branch achievement, Dr. Grant points to a study by Dr. Martin Paulus and colleagues at the University of California, San Diego.

The researchers performed fMRI while 46 men who had been abstinent from methamphetamine for about a month took a decisionmaking test. The researchers found that patterns of activation in certain brain regions predicted with high accuracy which men would and would not relapse 1 year later (see "Brain Activity Patterns Signal Risk of Relapse to Methamphetamine"). "This use of fMRI, if replicated, could be adapted for treatment and preventive interventions," Dr. Frascella says.

Behavioral and Brain Development

Led by Dr. Vincent Smeriglio, this Branch examines drug exposure and abuse, and their health and social consequences, through the course of human development—from the prenatal period through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Research focuses on:

- The effects of drugs on behavioral and brain development;

- The role of genetic, neurobiological, and environmental factors in youths' vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction; and

- The developmental effects of cooccurring exposure to drugs and infectious diseases as well as the impact of drug abuse on youths with mental illness.

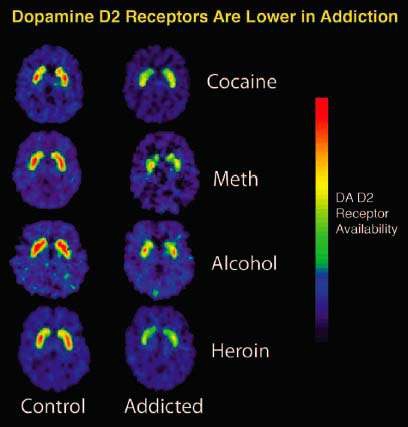

Brain Imaging is a Key Tool in Studies Sponsored by the Division of Clinical Neuroscience and Behavioral Research: The images below—used in a recent Division presentation—show that repeated exposure to drugs depletes the brain's dopamine receptors, which are critical for one's ability to experience pleasure and reward.

Brain Imaging is a Key Tool in Studies Sponsored by the Division of Clinical Neuroscience and Behavioral Research: The images below—used in a recent Division presentation—show that repeated exposure to drugs depletes the brain's dopamine receptors, which are critical for one's ability to experience pleasure and reward.One theme of the Branch's work is research to tailor drug abuse treatments to individual needs. As a recent example, a Branch-supported study by Dr. Leslie Jacobsen and colleagues at Yale University School of Medicine found that adolescent smokers experienced greater memory impairment during nicotine withdrawal if their mothers had smoked while pregnant. The study also produced fMRI evidence implicating particular brain regions in the deficits, which may be useful diagnostically as well as therapeutically.

Behavioral and Integrative Treatment

This Branch, under Dr. Lisa Onken's direction, aims to develop new and improved treatments for drug abuse and addiction, including behavioral, combined behavioral-pharmacological, and complementary and alternative treatments. The Branch designs new interventions, tests them for efficacy, and evaluates strategies to improve treatment engagement, adherence, and retention—key factors in success. The Branch also supports research that prepares treatments for use in community settings, where cost, training, and fit with existing services can be constraints.

"Behavioral therapies that work well in a research setting cannot necessarily be taken into the community. Oftentimes, they are too complicated and expensive, and require extensive training for clinicians," Dr. Frascella notes. One way of developing a community-friendly treatment is to identify the active ingredients of effective treatments, explains Dr. Onken. "In this way, we may be able to create more streamlined treatments that retain their potency. Another novel approach to making a treatment more community-friendly is to use computers to help counselors deliver treatment. For example, Dr. Kathleen Carroll at Yale University is testing the efficacy of computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy in preventing cocaine relapse.