Chronic exposure to cocaine depresses neural activity. Initially, the effect shows up mostly in the brain's reward areas. With longer exposure, however, neural depression spreads to circuits that form cognitive and emotional memories and associations, according to NIDA-funded research by Drs. Thomas J.R. Beveridge and Linda J. Porrino and colleagues at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

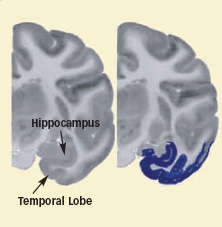

Long-Term Cocaine Exposure Blunts Temporal Lobe Activity in Monkeys: Blue coloring in these images represents areas of the temporal lobe that are less active after cocaine self-administration than after food self-administration. After 5 days of cocaine self-administration (left image), a monkey still shows normal activity in the temporal lobe area. In contrast, a monkey that self-administered cocaine for 100 days (right image) demonstrates lowered activity.

Long-Term Cocaine Exposure Blunts Temporal Lobe Activity in Monkeys: Blue coloring in these images represents areas of the temporal lobe that are less active after cocaine self-administration than after food self-administration. After 5 days of cocaine self-administration (left image), a monkey still shows normal activity in the temporal lobe area. In contrast, a monkey that self-administered cocaine for 100 days (right image) demonstrates lowered activity.Wider Effects With Longer Exposure

The researchers trained 14 male monkeys to press a lever for a reward. Six monkeys received banana-flavored food morsels, and eight received an infusion of cocaine (either 0.03 mg/kg or 0.3 mg/kg). Each monkey received up to 30 portions of food or infusions of cocaine daily for either 5 or 100 days. The 100-day trial, much longer than most other studies of drug use in primates, closely mimicked chronic cocaine abuse among people. For monkeys in the high-dose group, each session ended when they self-administered a dose equivalent to a person taking roughly 0.5-1.0 gram of cocaine per day. The researchers estimate that their experiment models a person heavily abusing cocaine daily for roughly 1 year.

After each monkey's final session, Dr. Porrino's team mapped its rate of cerebral glucose metabolism—the primary indicator of cerebral energy expenditure. The researchers injected a radiolabeled form of glucose (2-[14C]deoxyglucose; 2-DG) and, using autoradiography, obtained images that showed how much fuel different brain areas were utilizing (see image). Greater glucose metabolism indicates greater neural activity.

All the monkeys that had self-administered cocaine showed some localized depression of glucose metabolism. In the monkeys that self-administered cocaine daily for just 5 days, neural depression was largely restricted to pleasure and motivation areas, especially the reward circuit and areas that process expectations of rewards.

In the 100-day test, animals that had received the high dose of the drug revealed less neural activity in 40 of the 77 brain regions analyzed as compared with animals that had received only food morsels (see table below). The high-dose monkeys incurred a 16 percent drop, on average, in overall cerebral glucose metabolism. The low dose of cocaine depressed metabolism in 14 of the regions, but not overall.

The tests suggest that with longer exposure to cocaine, reductions in neural activity expand within and beyond the pleasure and motivation centers, says Dr. Porrino. "Within the structure called the striatum, the blunting of activity spreads from the nucleus accumbens, a reward area, to the caudate-putamen, which controls behavior based on repetitive action," she says. Long-term cocaine use also depressed memory and information-processing areas.

The findings accord well with those of human imaging studies, which have found general depression in cerebral blood flow among chronic cocaine abusers compared with nonabusers. By using animals, however, Dr. Porrino eliminated two sources of uncertainty in those clinical studies: differences in metabolic rates that may have predated cocaine abuse and abuse of drugs other than cocaine. "My team can directly attribute to cocaine the depressed brain metabolism observed in the study," says Dr. Porrino.

"Our 100-day experimental protocol for rhesus monkeys gives a good picture of what might happen in the brains of cocaine abusers," she says. "Some addiction researchers believe that the shift in activity within the striatum may, in part, underlie the progression from voluntary drug taking to addiction. Moreover, human imaging research has linked drug craving with the amygdala and insula, temporal lobe areas depressed by cocaine in our study."

| Name of area | Selected roles in behavior | Depression of metabolic activity* (percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus accumbens (ventral striatum) | Processes reward and motivation | 16-31 |

| Caudate-putamen (dorsal striatum) | Controls behaviors based on repetitive action | 10-23 |

| Hypothalamus | Controls eating, fighting, mating, and sleep | 18-22 |

| Insula | Translates body signals into subjective feelings | 17-19 |

| Hippocampus | Consolidates memories and influences mood | 15-23 |

| Amygdala | Forms emotional and motivational memories, e.g., linking a cue and a drug to produce craving | 13-19 |

| Temporal cortex areas | Processes emotional and cognitive information, e.g., recognition and short-term memory | 17-22 |

* Animals self-administering cocaine at either dose were compared with animals self-administering food.

"The reduced activity of the temporal lobe indicates that this structure is somehow compromised," says Dr. Nancy Pilotte of NIDA's Division of Basic Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. "Some of these regions mediate the ability to connect emotionally, and cocaine's blunting of them may induce a flattened affect similar to depression symptoms that are common among chronic cocaine abusers."

"Dr. Porrino and her colleagues have identified key brain structures affected by long-term cocaine exposure and have provided a valuable set of observations that could serve as a basis for future research," Dr. Pilotte says. For example, she adds, researchers might now focus on those regions when gauging the effectiveness of potential medications for cocaine addiction or when measuring recovery after abstinence.

Sources

Beveridge, T.J.R., et al. Chronic cocaine self-administration is associated with altered functional activity in the temporal lobes of nonhuman primates. European Journal of Neuroscience 23(11):3109-3118, 2006. [Abstract]

Porrino, L.J., et al. The effects of cocaine: A shifting target over the course of addiction. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 31(8):1593-1600, 2007. [Abstract]