"My body forgot the urge to smoke." That's how one patient with damage to the insula, an area of the brain within the cerebral cortex, described the after effects of his stroke on his smoking habit. He is not alone. NIDA-funded investigators repeatedly heard of similar experiences while interviewing people who had sustained brain injuries.

Many people who have suffered a stroke or other brain injury try to quit smoking out of concern for their health, says Dr. Antoine Bechara of the University of Southern California and the University of Iowa. Most have difficulty. "In some brain injury patients, however, the urge to smoke seemed to be switched off, while other desires, such as for food, were not disrupted," says Dr. Bechara. He and his colleagues found that the experience of quitting cigarettes immediately, easily, and without relapse was much more common among people with damage to the insula than those with injuries elsewhere in the brain. If Dr. Bechara's preliminary findings are validated, the insula is likely to become an important target for future addiction research.

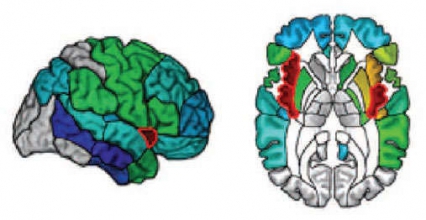

Brain Region Linked to Sudden Cessation of Smoking: In these two views of the brain, red indicates regions where damage was associated with the sudden disruption of cigarette addiction in 12 of 19 patients. The regions identified are the right and left insula, which other studies have linked to emotional feelings and cue-induced drug urges.

Brain Region Linked to Sudden Cessation of Smoking: In these two views of the brain, red indicates regions where damage was associated with the sudden disruption of cigarette addiction in 12 of 19 patients. The regions identified are the right and left insula, which other studies have linked to emotional feelings and cue-induced drug urges.Different Experiences of Smoking Cessation

Scientists suspect that in chronic abusers, drugs or drug-associated cues produce bodily sensations that the insula relays to other brain areas as urgent needs. To explore the insula's role in addictive behavior, Dr. Bechara's team contacted men and women who had suffered brain damage and were listed in the Patient Registry of the Division of Behavioral Neurology and Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Iowa.

Before suffering brain damage, mostly from stroke, all the participants had been long-term, heavy cigarette smokers; on average, they had smoked a pack and a half a day for 27 years.

The patients' brains had been injured 8 years before the study, on average, and 32 of the 69 patients had quit smoking immediately following their injury or some time thereafter. The researchers used brain imaging to verify injury locations: 19 patients had insula lesions, and 50 showed damage to other regions. Patients with damage in the insula and those with damage to other regions were matched for the number of cigarettes smoked and duration of smoking before the injury.

Patients with insula and noninsula damage were equally likely to have quit smoking cigarettes after their brain injury. To identify those whose smoking addiction had ceased suddenly, the researchers settled on four criteria: quitting cigarettes less than a day after lesion damage; reporting no relapse after quitting; rating the difficulty of quitting as less than 3 on a scale of 1 (very easy) to 7 (very difficult); and reporting no urges to smoke since quitting.

Of the 32 patients who quit smoking, 16 met all four criteria and were designated as having "disrupted smoking addiction." They included 12 of the 13 patients with lesions in the insula who quit smoking, but just 4 of the 19 quitters with lesions only in other areas. "The much higher likelihood of disrupted smoking among patients with insula damage was striking and suggests that the area is a prime candidate in drug-taking urges," notes Dr. Bechara.

"For patients with insula damage, it seems that smoking quit them—they lost the desire to smoke—which is a provocative and unexpected finding," says Dr. Steven Grant of NIDA's Division of Clinical Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. "Dr. Bechara's results have cast a searchlight onto a relatively new area of interest among addiction researchers."

New Focus for Drug Abuse Research

Current interest in the role of the insula in drug abuse was sparked a few years ago by research that linked activity in that brain area with abstinence in methamphetamine abusers ("Brain Activity Patterns Signal Risk of Relapse to Methamphetamine (Archives)"). Recent studies have also tied insula activation to cravings and drug administration among substance abusers. According to Dr. Bechara, his team's next step is to examine urges for and abuse of substances—cigarettes, alcohol, and illicit drugs—in a larger number of patients who have recently suffered damage to the insula and other parts of the brain.

"Our findings so far suggest that the insula may be a structure to target in the development of new smoking cessation medications," Dr. Bechara says. "Obviously, damaging the insula is not a therapeutic option." But scientists could determine the types of receptors present in the insula, for example, and then test whether blocking them blunts nicotine reward.

Drs. Bechara and Grant agree that with animal protocols that mimic different aspects of addiction—reward, craving, and relapse—scientists may learn what specific role the insula plays in drug abuse.

Source

Naqvi, N.H., et al. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science 315(5811):531-534, 2007. [Abstract]