For up to 6 weeks after smokers quit, their brain cells have more nicotine-binding receptors than nonsmokers' cells do, according to a recent NIDA-funded study. Scientists speculate that the brain develops extra receptors to accommodate the large doses of nicotine from tobacco and that the resulting expanded receptor pool contributes to craving and other discomforts of smoking withdrawal.

The Challenge of Quitting Cold

"In smokers who quit cold turkey, the brain has a big adjustment to make—excess receptors and little nicotine to fill them," says investigator Dr. Julie K. Staley of Yale University School of Medicine. "The brain is used to having nicotine stimulate all those receptors, and when they are not stimulated, it needs time to adapt to the loss of nicotine. Withdrawal symptoms occur until the brain has had sufficient time to make the neurochemical adaptations necessary for a person to feel normal without nicotine."

In the study by Dr. Staley, Dr. Kelly Cosgrove, and colleagues, 19 nicotine-dependent people, who had smoked about a pack a day for an average of 21 years, underwent imaging by single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) at various times after they quit. The technique measured β2 nicotinic acetylcholine (β2*-nACh) receptors, which are the most prevalent nicotinic receptor subtype and contribute to the rewarding aspects of nicotine.

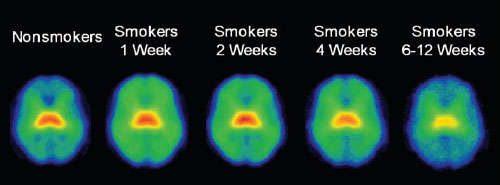

Smokers Demonstrate Excess Nicotinic Receptors During First Month of Abstinence: The predominance of green rather than blue in these brain scans of abstinent smokers indicates higher than normal levels of β2*-nACh receptors. Smokers continue to show elevated amounts of the receptors through 4 weeks of abstinence, but levels normalize by 6 to 12 weeks.

Smokers Demonstrate Excess Nicotinic Receptors During First Month of Abstinence: The predominance of green rather than blue in these brain scans of abstinent smokers indicates higher than normal levels of β2*-nACh receptors. Smokers continue to show elevated amounts of the receptors through 4 weeks of abstinence, but levels normalize by 6 to 12 weeks.During the first month of abstinence, images of the former smokers showed higher levels of β2*-nACh receptors in several brain areas than did images of nonsmokers who were matched for age, gender, and race. The former smokers had, on average, 21 to 29 percent more of the receptors in the cerebral cortex, the brain area responsible for thinking; 24 percent more, on average, in the cerebellum, which regulates sensation and movement; and 22 percent more in the striatum, which produces feelings of reward. After 6 to 12 weeks of abstinence, the former smokers' brain receptor levels tended to match those of nonsmokers, although there was significant variation among individuals.

The temporarily elevated pool of β2*-nACh receptors may explain why the first months of smoking cessation are difficult for many people. The researchers surmise that smokers' larger complement of β2*-nACh receptors indicate that their brains have adapted to nicotine, so normal operation requires high levels of stimulation. When a smoker quits and nicotine no longer floods the brain, the reduced stimulation might disrupt the receptors' regulation of dopamine and other neurochemicals involved in the reinforcing effects of smoking. Dopamine depletion in the reward system has been linked to lethargy, moodiness, and other symptoms seen in smoking cessation. Also, research by Dr. Arthur Brody at the University of California, Los Angeles has associated the α4β2*-nACh receptor—a subset of the β2*-nACh receptors measured by Dr. Staley's team—with craving ("Imaging Studies Elucidate Neurobiology of Cigarette Craving").

Focus on Smokers With Mental Disorders

The neurochemicals influenced by stimulation of the β2*-nACh receptors are also implicated in many psychiatric illnesses—including anxiety disorders, depression, and schizophrenia. People with these disorders are more likely to smoke than those who do not have mental health problems. Accordingly, Dr. Staley and colleagues are beginning to explore neurobiological underpinnings that may connect smoking and mental illnesses, and they are targeting the β2*-nACh receptor. In a recent study, they found that high β2*-nACh receptor levels in the thalamus, a structure that acts as a switchboard for signals traveling between brain regions, are associated with recurring symptoms of anxiety among nonsmokers with posttraumatic stress disorder. The researchers also are tracking changes in the receptors after smoking cessation among people with schizophrenia and depression.

"Dr. Staley's results reveal the impact of smoking on nicotinic receptors in the brain and establish a baseline that future researchers can use to assess the effects of different treatments on receptor normalization," says Dr. Ro Nemeth of NIDA's Division of Clinical Neuroscience and Behavioral Research.

Source

Cosgrove, K.P., et al. β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor availability during acute and prolonged abstinence from tobacco smoking. Archives of General Psychiatry 66(6): 666-676, 2009. [Abstract]