Methadone maintenance and therapeutic communities are two effective treatment approaches that are seldom combined. Few methadone patients apply to therapeutic communities, and few therapeutic communities will accept them. Methadone patients may anticipate that therapeutic communities will be inhospitable because many therapeutic communities traditionally have held that recovery requires abstinence from all psychoactive drugs, including medications. Therapeutic communities may be concerned that admitting methadone-reliant individuals could undermine other members' unity of purpose, threatening their progress. Practical and logistical difficulties add to the challenge of merging the two treatments.

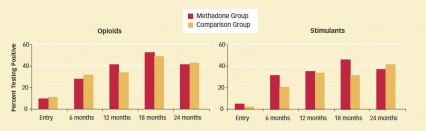

Methadone Patients Fare as Well as Drug-Free Patients in a Therapeutic Community Setting: At half-yearly assessments, the proportions of methadone and comparison-group patients testing positive for illicit opioid or stimulant use were statistically equivalent. In both groups, the number of individuals using opioids or stimulants increased as more people left the treatment program. All study participants were tracked for 2 years whether or not they left treatment; participants who switched into methadone treatment during the study are included among the comparison group in this graph. Read the full description of Methadone Patients Fare as Well as Drug-Free Patients in a Therapeutic Community Setting.

Methadone Patients Fare as Well as Drug-Free Patients in a Therapeutic Community Setting: At half-yearly assessments, the proportions of methadone and comparison-group patients testing positive for illicit opioid or stimulant use were statistically equivalent. In both groups, the number of individuals using opioids or stimulants increased as more people left the treatment program. All study participants were tracked for 2 years whether or not they left treatment; participants who switched into methadone treatment during the study are included among the comparison group in this graph. Read the full description of Methadone Patients Fare as Well as Drug-Free Patients in a Therapeutic Community Setting.In a recent NIDA-funded study, Dr. James Sorensen and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, showed that these issues, although significant, need not be prohibitive. Opioid-dependent patients who were taking methadone upon admission to a therapeutic community fared as well as the rest of the community over 2 years of followup.

Equivalent Results

The researchers recruited 145 men and 86 women at the time of their admission to Walden House, a San Francisco therapeutic community that has been accommodating methadone patients for over 2 decades. All the participants were opioid-dependent and met eligibility criteria for methadone maintenance therapy, and roughly half were receiving methadone. The methadone patients were similar to the others in terms of co-occurring stimulant abuse, psychiatric history, criminal justice involvement, and expected length of stay in the therapeutic community.

At the beginning of the study and then at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, the researchers tested participants for use of illicit opioids, alcohol, and stimulants (cocaine and amphetamine) and questioned them about drug injection and risky sexual behaviors. They used the program's client database and staff logs to determine participants' retention in treatment. Previous studies had indicated that the longer patients stay in treatment, the greater their likelihood of recovery.

Many Patients Still Receive Lower Than Recommended Methadone Doses

Methadone is a synthetic agent that relieves symptoms of withdrawal from heroin and other opioids by occupying the same brain receptor as those drugs. This therapy has been shown to have many benefits, including reductions in illicit drug use, needle-associated diseases, and crime. The treatment can also help a person work and participate in other normal social interactions.

In the United States, there are about 1,400 methadone maintenance programs serving over 254,000 patients, according to a 2006 report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Research has established that most patients require a methadone dose of 60-120 mg/day, depending on their individual responses, to achieve optimum therapeutic effects. Yet, a study by Drs. Harold Pollack and Thomas D'Aunno at the University of Chicago found that many methadone patients receive lesser doses.

In 1988, 1990, and then at 5-year intervals through 2005, the researchers surveyed nationally representative samples of 146 to 172 outpatient treatment facilities. Although the proportion of patients receiving doses below the recommended minimum decreased during this 17-year span, 34 percent of patients in 2005 still received methadone doses of less than 60 mg/day, while 17 percent received doses below 40 mg/day. The study also found that methadone programs strongly advocating an abstinence recovery goal were the most likely to provide doses of methadone below 60 mg/day.

Source

Pollack, H.A., and D'Aunno, T. Dosage patterns in methadone treatment: Results from a national survey, 1988–2005. Health Services Research 43(6):2143–2163, 2008. [Abstract]

By all measured outcomes, the methadone patients were statistically indistinguishable from patients who were not receiving that medication. In particular, both groups of patients stayed in treatment for similar periods of time and had similar success rates in avoiding illicit opioids and stimulants (see graph).

"The methadone patients' outcomes were entirely equivalent to those of other patients," says Dr. Sorensen. "That removes one reason for not admitting them to therapeutic communities."

Necessary Adjustments

During the past decade, some therapeutic communities have modified their programs to be accessible to a broader range of patients, such as those with psychiatric disorders. Some of these individuals receive medications to treat their conditions, "but methadone still remains an issue," says Dr. Sorensen.

A 2005 national survey of 380 therapeutic communities by the Institute of Behavioral Research at the University of Georgia found that only 7 percent of therapeutic communities integrated methadone treatment into their programs. A more recent survey by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration determined that among residential treatment settings, including halfway houses and therapeutic communities, only 3.6 percent used methadone in their opioid-treatment programs.

Therapeutic communities wishing to integrate methadone patients into their programs must teach staff and their other patients to understand the medication's effects and counter negative attitudes toward it, says Dr. Sorensen. "There has to be training about what it is like to be on methadone and how to work with individuals who are taking it. A program needs to provide staff with strategies that they can use in working with issues specific to patients who take methadone, such as being drowsy and falling asleep at meetings." He notes that similar problems arise with other psychiatric medications.

There also are practical hurdles, such as difficulty in supplying the medication. In the United States, methadone is typically provided in highly regulated clinics that patients initially have to visit each day to receive their dose; only after several months of adherence to the clinic's regulations are patients allowed to take home a supply of methadone. Unsupervised trips to a methadone clinic may expose therapeutic community patients to risks such as encounters with drug dealers or old acquaintances who are still abusing drugs. Thus, a residential facility accepting methadone patients needs to provide transportation to and from the clinics, as well as a secure place for storing and administering the medication.

All these provisions require additional staff and resources, and thus add costs. Yet for therapeutic communities that make the investment, the payoff is the capacity to provide more patients with the benefits of the therapeutic community model: a safe place to interact with peers who share experiences, an emphasis on self-reliance, a program of motivational reinforcement, and a dedication to recovery.

Dr. Sorensen and colleagues note that therapeutic communities that adjust to accommodate methadone patients give residents a useful treatment option. At the 2-year mark of the study, a significant number—about 30 percent—of the individuals who started their residencies in the drug-free group had initiated methadone maintenance therapy. Methadone maintenance patients, in contrast, tended to continue with their original therapy.

"It is not a trivial matter to incorporate methadone treatment in a residential treatment setting, but we encourage therapeutic communities to do so," says Dr. Sorensen. "In that way, they can expand the care they are providing to reach more patients."

"Dr. Sorensen has shown that therapeutic communities can support the recovery of patients regardless of whether their therapeutic goals are abstinence or long-term maintenance," says Dr. Thomas F. Hilton of NIDA's Health Services Research Program. Partly because of Dr. Sorensen's work, there is now a growing openness toward the integration of different medical treatment approaches within therapeutic communities, including addiction pharmacotherapies. "Dr. Sorensen's research is helping therapeutic communities evolve so that they can reach a broader spectrum of patient recovery needs," Dr. Hilton adds.

Correction

An earlier version of this article attributed the 2005 survey of therapeutic communities to the Institute for Behavioral Research at Texas Christian University instead of at the University of Georgia.

Sources

Chen, T., et al. Residential treatment modifications: Adjunctive services to accommodate clients on methadone. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 35(2):91–94, 2009. [Abstract]

Hettema, J.E., and Sorensen, J.L. Access to care for methadone maintenance patients in the United States. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 7(3):468–474, 2009. [Full Text]

Sorensen, J.L., et al. Methadone patients in the therapeutic community: A test of equivalency. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 100(1-2):100–106, 2009. [Full Text (PDF, 565KB)]