In this study:

- The Raising Healthy Children (RHC) intervention delivered to elementary school children was associated with improved outcomes for the children of the original intervention recipients—potentially a transgenerational effect.

- Children of RHC recipients showed improved developmental functioning before age 5, as well as fewer problem behaviors; better academic, cognitive, and emotional skills; and less risk behavior from ages 6 to 18.

Preventive interventions delivered to school-aged children and their caregivers and teachers offer a promising approach to head off the onset of substance use and other harmful behaviors during adolescence. Several trials of such interventions initiated in the 1980s and following participants over long periods of time have demonstrated that behavioral and health benefits could be sustained well into the participants’ adulthood.

A recent NIDA-sponsored study now suggests the intriguing possibility that such benefits can even be passed on to the next generation—that is, the children of the original recipients of the intervention. “People have long noted that early adversity can have long-term negative cascading effects,” explains Dr. Karl Hill, the study’s lead author, from the University of Colorado Boulder. “This study suggests that interventions to improve development may similarly trigger positive developmental cascades across generations.”

The Raising Healthy Children Intervention and Its Followup

Dr. Hill and colleagues from the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Washington examined the outcomes of the children of people who received an intervention called Raising Healthy Children (RHC). This intervention was delivered in the 1980s to grades 1 to 6 at elementary schools in disadvantaged Seattle neighborhoods and provided specialized training for teachers, parents, and the children themselves. For example, teachers participated in workshops for improved classroom management and instruction; parents received training through workshops or in-home problem-solving sessions on family management and how to help their children succeed in school; and children received social and emotional skill development, as well as summer camps or in-home services for students with academic or behavior problems.

About 800 children had been assigned either to the RHC intervention (not all of them receiving the full intervention) or to a control group, and they were followed until they reached age 39 in 2014. Analysis identified numerous improved outcomes in those who had received the full RHC intervention (see Table).

| Significant Effects on Participants* | Significant Effects on Participants’ Children** |

|---|---|

|

Improved outcomes at age 18

Improved outcomes at age 21

Improved outcomes at ages 24 to 27

|

Improved outcomes at ages 1 to 5

Improved outcomes at ages 6 to 18

|

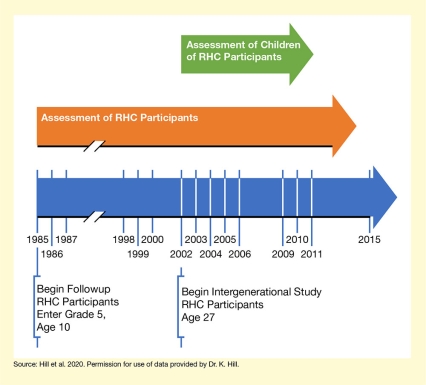

During that time, many of the participants became parents themselves, prompting Dr. Hill and his team to ask if the intervention differences could be transferred to the next generation. To address this, they conducted a separate analysis that included those participants who had become parents and their oldest biological child with whom they had face-to-face contact at least once a month (see Figure).

Dr. Hill and his team then evaluated these children on several outcomes, including:

- Developmental functioning at ages 1 to 5 years as reported by the parents.

- Problem behaviors; academic, cognitive, and emotional skills; as well as grades and performance at ages 6 to 18 based on teacher reports.

- Risk behaviors (e.g., substance use, early onset of sex, delinquency) at ages 6 to 18 based on the children’s self-reports.

The analyses included 72 youths whose parents had received the initial RHC intervention and 110 youths whose parents had been in the control group. By the last data collection, the youths ranged in age from 1 to 22 years.

Children of RHC Participants Showed Improved Outcomes

The analyses demonstrated significant differences between children whose parents had received the RHC intervention and those whose parents were in the control group (see Table). For example, up to age 5, children of parents in the RHC group had fewer developmental delays in communication skills, gross and fine motor skills, and an overall measure of developmental functioning. They also had lower teacher-rated scores on certain externalizing problem behaviors (e.g., oppositional defiance, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and an overall externalizing measure) and higher scores on academic, cognitive, and emotional skills at ages 6 to 18. Finally, children of parents receiving the RHC intervention were significantly less likely to have tried any drugs (i.e., alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana) by age 18; to a lesser extent, they also showed reductions in other risk behaviors.

It is not yet clear which factors mediate the intervention’s transgenerational impact. Dr. Hill points to previous analyses showing that adults who had received the RHC intervention in elementary school showed significantly more healthy close relationships, better mental and physical health, better socioeconomic success, and generally more positive adult functioning. The researchers speculate that growing up in families with these characteristics would contribute to the better outcomes of the next generation they studied.

Dr. Hill is excited about the potential implications of their observations. “The findings suggest that a universal intervention delivered in childhood can have long-lasting consequences not only into adulthood, but into the next generation,” he says. Nevertheless, he cautions that this was only one study with a quasi-experimental design, and that the results must be replicated with more samples and other interventions before broad conclusions can be drawn. If the findings can be supported, however, these extended benefits could significantly improve future cost-benefit analyses of preventive interventions.

This research was supported by NIDA grants DA12138, DA023089, DA033956, and DA09679.

- Text Description of Figure

-

The figure illustrates the study design. The bottom blue arrow shows the timeline of the RHC study and its intergenerational followup, beginning from 1985 at the far left to 2015 on the far right of the arrow. As indicated below the arrow, 1985 marked the beginning of the followup phase of the RHC intervention, when participants entered grade 5 at age 10, and 2002 marked the beginning of the intergenerational study, when RHC participants were age 27. White lines represent years in which the children of RHC participants were assessed in the intergenerational study. The orange arrow in the middle represents the period during which RHC participants were assessed, from 1985 to 2014. The green arrow at the top indicates the period during which the children of RHC participants were assessed, from 2002 to 2011.

Source:

- Hill, K.G., Bailey, J.A., Steeger, C.M., et al. Outcomes of childhood preventive intervention across 2 generations: A nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(8):764-771. Doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1310.