These studies found that:

- Collaborations between physicians with buprenorphine waivers and community pharmacists in the treatment of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) are feasible and acceptable to both providers and patients.

- Policies to allow methadone administration and dispensation at Federally Qualified Health Centers or community pharmacies could expand access to methadone treatment for patients with OUD, particularly in underserved rural communities.

Treating patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) with methadone or buprenorphine can prevent overdose deaths and other opioid-related harms. Currently, methadone can only be administered or dispensed in federally certified opioid treatment programs (i.e., methadone clinics), but only a minority of U.S. counties have such facilities, limiting treatment access for many patients. Similarly, buprenorphine can be prescribed only by physicians who have received a special waiver; the numbers of those physicians are also limited. Two recent NIDA-sponsored studies indicate that allowing licensed community pharmacists to dispense buprenorphine or methadone under certain conditions may help alleviate treatment barriers for people with OUD, especially those living in rural areas with limited treatment providers. Licensed community pharmacists are experts in medication therapy management, are used to dispensing medications (including medications to treat OUD), and are therefore natural partners of prescribers.

Physician–Pharmacist Collaboration in Buprenorphine Treatment Is Feasible and Accepted by Patients

*PDMP = prescription drug monitoring program

See full text description at end of article.

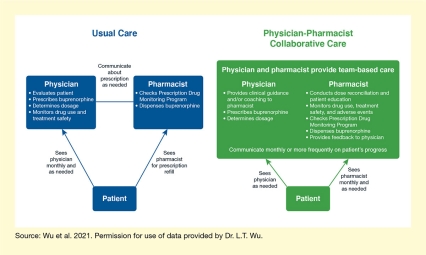

Dr. Li-Tzy Wu and colleagues from Duke University and other institutions conducted a pilot study assessing the feasibility of a collaborative care model involving buprenorphine-waivered physicians and licensed community pharmacists. In this model, physicians and pharmacists form a care team in which the physician provides clinical guidance and prescribes the buprenorphine, whereas the pharmacist dispenses the buprenorphine, educates the patient on its use, monitors drug use and treatment safety, and checks the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program to help prevent any medication diversion. Physician and pharmacist communicate at least monthly, and patients see the physician as needed. This contrasts with the “usual care” approach, in which pharmacist and physician communicate infrequently and the pharmacist only dispenses the buprenorphine and checks the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (Figure 1).

In the study, patients with OUD were switched from traditional office-based buprenorphine treatment delivered by a physician to community pharmacy care for 6 months. The researchers then monitored outcomes such as treatment retention and adherence; use of opioids and other drugs; patient safety; and treatment satisfaction of patients, physicians, and pharmacists. The team found that almost 90 percent of patients remained in treatment at the end of the 6 months and that overall, participants had shown treatment adherence (i.e., had taken any of the dispensed medication) at 95 percent of study visits; only 5 percent of patients for whom all drug screens had been collected had any opioid-positive urine tests during the study period. Additionally, patients appreciated that they could conduct their buprenorphine visits at the same place where they received the medicine. Dr. Wu adds, “All groups of study participants, including buprenorphine-waivered physicians, community pharmacists, and patients with OUD, were satisfied with this new treatment model.” However, larger studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of this model of physician–pharmacist collaboration for buprenorphine treatment.

Methadone Dispensation in FQHCs and Pharmacies Could Significantly Enhance Access

Methadone treatment is hampered by the fact that many counties in the United States, particularly in rural areas, do not have facilities certified to dispense the medication. This presents a unique barrier for many patients with OUD because methadone must be administered daily under supervision for at least the first 3 months of treatment. Even with the relaxation of these requirements during COVID-19, methadone treatment still requires patients to travel frequently for medication administration. Current federal regulations allow for methadone dispensation at satellite medication units such as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) or pharmacies; however, state regulations frequently prevent adoption of this process. In 2019, Ohio allowed FQHCs to act as medication units for methadone dispensation, but pharmacies were not included in this policy, even though the wide availability of community pharmacies and licensed pharmacists could help expand access to methadone treatment.

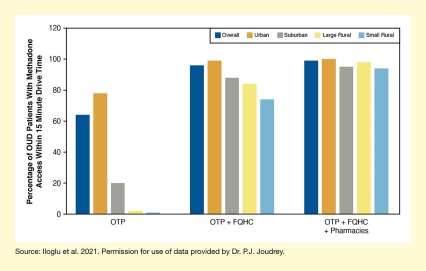

To quantify the potential impact of increasing methadone dispensation sites, Dr. Suzan Iloglu, Dr. Paul J. Joudrey, and their colleagues from Yale University conducted a modeling study estimating the proportion of patients with OUD in Ohio who would be able to reach a methadone dispensation site within 15 minutes’ drive time with and without inclusion of FQHCs and Walmart pharmacies. They also determined the effects specifically for urban, suburban, large rural, and small rural zip codes.

The model showed that with current opioid treatment programs, only 64 percent of people with OUD could reach a methadone dispensation site within 15 minutes; this proportion increased to 96 percent with the addition of FQHCs and to 99 percent with the addition of both FQHCs and Walmart pharmacies. Availability of a treatment site within 15 minutes increased particularly in currently underserved rural zip codes (see Figure 2). “In the most rural communities and for patients facing transportation barriers, utilization of additional clinical sites such as pharmacies may be needed to ensure access to methadone treatment,” says Dr. Joudrey. While this was only a modeling study, the results suggest that increased adoption of medication unit policies at the state level could greatly expand access to methadone treatment in the United States, particularly in currently underserved rural areas.

This work was supported by NIDA grants DA040317, DA033312, DA049282-01, DA15612-16, DA050072, and DA033312.

- Text Description of Figure 1

-

The figure compares the usual care model for buprenorphine treatment (blue boxes on the left) and the physician-pharmacist collaborative care model (green boxes on the right). In the usual care model, physician and pharmacist act separately but communicate about the prescription as needed, as indicated by the two separate blue boxes at the top. The patient, represented by the small blue box at the bottom, interacts with both physician and pharmacist, as indicated by the two blue arrows. In the physician-pharmacist collaborative care model, physician and pharmacist provide team-based care, as indicated by the single green box at the top. The patient, represented by the small green box at the bottom, still interacts with both physician and pharmacist, as indicated by the two green arrows.

- Text Description of Figure 2

-

The bar chart shows the effect of expanding methadone dispensation facilities on patient access to methadone treatment. Dark blue bars indicate overall patient access, brown bars indicate patient access in urban zip codes, gray bars indicate patient access in suburban zip codes, yellow bars indicate patient access in large rural zip codes, and light blue bars indicate access in small rural zip codes. The vertical y-axis indicates the percentage of patients with OUD who have access to methadone within 15 minutes driving time, on a scale from 0 to 100%.

If dispensation can only occur at current opioid treatment programs (OTPs) (left set of bars), the percentage of patients with methadone access within 15 minutes driving time is 64% of patients overall, 78% of patients in urban zip codes, 20% of patients in suburban zip codes, 2% of patients in large rural zip codes, and 1% of patients in small rural zip codes. If dispensation can occur at OTPs plus FQHCs (middle set of bars), the percentage of patients with methadone access within 15 minutes driving time is 96% of patients overall, 99% of patients in urban zip code, 88% of patients in suburban zip codes, 84% of patients in large rural zip codes, and 74% of patients in small rural zip codes. If dispensation can occur at OTPs, FQHCs, plus Walmart pharmacies (right set of bars), the percentage of patients with methadone access within 15 minutes driving time is 99% of patients overall, 100% of patients in urban zip codes, 95% of patients in suburban zip codes, 98% of patients in large rural zip codes, and 94% of patients in small rural zip codes.

Sources:

- Wu, L.T., John, W.S., Ghitza, U.E., et al. Buprenorphine physician-pharmacist collaboration in the management of patients with opioid use disorder: Results from a multisite study of the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. Addiction 2021;116(7):1805–1816.

- Iloglu, S., Joudrey, P.J., Wang, E.A., et al. (2021). Expanding access to methadone treatment in Ohio through federally qualified health centers and a chain pharmacy: A geospatial modeling analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2021;220:108534. Full Text