This study found that:

- Urinary levels of breakdown products of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) found in cigarette smoke were significantly higher in Black than in white people who smoke cigarettes.

- For certain compounds (ethylene oxide and methylating agents), urinary levels were higher in women than in men of the same race.

- Black people had significantly higher intake of almost all VOCs per cigarette than white people.

Cigarette smoking is responsible for about 480,000 deaths per year in the United States, and millions more people suffer from smoking-related illnesses. However, disparities in tobacco use and its consequences exist across racial and ethnic groups. For example, while similar proportions of white and Black people report smoking, Black people tend to start smoking later than white people and report smoking fewer cigarettes per day and on fewer days per month. Despite these lower smoking levels, Black people who smoke have a higher risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease than white people who smoke.

A recent NIDA-funded study provides a potential explanation for the increased vulnerability to smoking-related health effects among Black people. The researchers demonstrated that for any given smoking level, Black people take in higher levels of toxic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are present in tobacco smoke compared with white people. The study’s lead author, Dr. Gideon from the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) says, “Our results add to the growing body of literature showing that Black people who smoke are exposed to higher levels of toxic chemicals from tobacco smoke even though they are generally ‘light smokers.’ This may help explain the higher lung cancer incidence among Black people compared to other racial groups."

Black People Who Smoke Take in More VOCs Than White People

Dr. St.Helen and his team from UCSF and other institutions hypothesized that Black people who smoke have higher lung cancer rates than their white counterparts despite smoking fewer cigarettes over their lifetime because they inhale more nicotine and other cancer-inducing (i.e., carcinogenic) substances in tobacco smoke per cigarette smoked. “Volatile organic compounds are abundant in tobacco smoke, and many are quite toxic and carcinogenic. We wanted to assess whether there are differences in breakdown substances of these toxic compounds in the urine of Black and white people who smoke,” explains Dr. St.Helen. Detection of the breakdown substances (or metabolites) in urine indicates exposure to the VOCs.

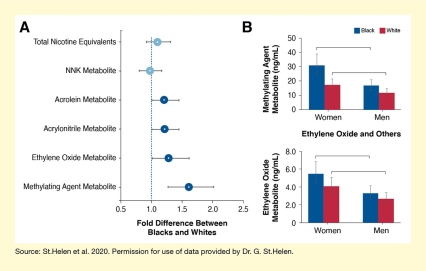

Note: NNK = nicotine-derived nitrosoamine ketone, a key tobacco-specific chemical derived from nicotine that is important in carcinogenesis.

See full text description at end of article.

The team used urine samples from 182 Black and 184 white individuals age 40 and older who smoked cigarettes and had participated in an unrelated study. They measured the levels of breakdown products (i.e., metabolites) of 10 toxic and carcinogenic VOCs in these samples. The analyses revealed that the metabolite concentrations of four VOCs—acrolein, acrylonitrile, ethylene oxide, and methylating agents—were higher in the urine of the Black than in the white participants (see Figure). For two of these VOCs—ethylene oxide and methylating agents—the analyses also detected sex differences, with both Black and white women having higher levels than their male counterparts.

Racial Differences Exist in VOC Intake Per Cigarette

To exclude that the differences between Black and white people stemmed from differences in smoking levels, the team also calculated the VOC metabolite levels per number of cigarettes smoked per day. Dr. St.Helen says, “Concentrations of the compounds we measured divided by the number of cigarettes smoked per day were also higher in Black compared to white participants, indicating that Black smokers are exposed to higher levels of these chemicals per cigarette compared to white smokers.” Further analyses confirmed that these differences indeed resulted from higher VOC intake in Black people, rather than from differences in VOC metabolism between the two groups. Higher intake of VOCs by Black smokers could be related to differences in cigarette products used, to differences in smoking behavior (e.g., depth of inhalation or other aspects of smoking style), or both.

The increased VOC metabolite levels detected in Black people who smoke compared with white people with similar smoking levels may provide a plausible explanation why Black people are more likely to develop smoking-related illnesses such as lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. Further studies are needed, however, to determine why exactly Black smokers inhale more toxic compounds per cigarette than their white counterparts.

This research was supported by NIDA grants DA031659, DA02277, DA012393, and DA035163.

- Text Description of Figure

-

The figure shows that Black people who smoke had higher levels of some VCO metabolites than white people who smoke. The left panel illustrates the difference for several metabolites. The horizontal x-axis shows the fold difference, or ratio, between Black people and white people who smoke on a scale from 0.5 to 2.5, with 1.0 indicating equal levels. Light blue circles (top two rows) indicate no significant difference between Black and white people who smoke, whereas dark blue circles (rows 3 to 6) indicate a significant difference. For total nicotine equivalents (top row) the ratio was 1.10, for the nicotine-derived nitrosoamine ketone (NKK) metabolite (row 2) it was 0.96, for the acrolein metabolite (row 3) it was 1.21, for the acrylonitrile metabolite (row 4) it was 1.20, for the ethylene oxide metabolite (row 5) it was 1.28, and for the methylating agent metabolite (row 6) it was 1.60.

The two right panels show the differences of metabolites for methylating agents (top) and ethylene oxide (bottom) between Black and white men and women who smoke. Blue bars indicate Black people and red bars indicate white people. The left pair of bars in both panels represents women and the right pair of bars represents men. In the top panel, the vertical y-axis shows the concentration of the methylating agent metabolite on a scale from 0 to 50 ng/mL. The concentration was about 30 ng/mL for Black women who smoke, about 18 ng/mL for white women who smoke, about 18 ng/mL for Black men who smoke, and about 13 ng/mL for white men who smoke. Horizontal black lines indicate a significant difference between women and men in both groups. In the bottom panel, the vertical y-axis shows the concentration of the ethylene oxide metabolite on a scale from 0 to 8.0 ng/mL. The concentration was about 5.0 ng/mL for Black women who smoke, about 4.0 ng/mL for White women who smoke, about 3.5 ng/mL for Black men who smoke, and about 2.5 ng/mL for white men who smoke. Horizontal black lines indicate a significant difference between men and women in both groups.

Source:

- St.Helen, G., Benowitz, N.L., Ko, J., et al. Differences in exposure to toxic and/or carcinogenic volatile organic compounds between Black and White cigarette smokers. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 2021;31(2):211–223.