Current prevention strategies have reduced the incidence of HIV worldwide, but that decline has slowed in recent years. We need new prevention strategies if we are to realize President Obama’s goal of an AIDS-free generation. Targeting people who inject drugs with treatment as prevention (i.e., Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain) and other measures is a high priority, since injecting drug use causes one in ten new cases of HIV worldwide and, in some countries, accounts for over 80 percent of new cases.

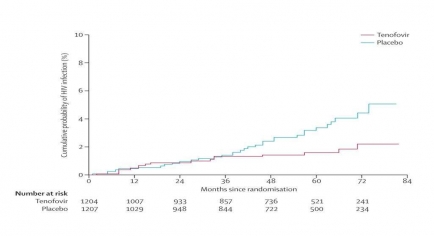

A new strategy to help reduce the spread of HIV among injection drug users is using antiretroviral drugs prophylactically. A phase 3 clinical trial whose results were published in June in The Lancet found that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with an oral antiretroviral medication called tenofovir reduced the transmission of HIV among injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand by nearly 50 percent, compared to a control group receiving a placebo (see graph). Increased adherence strengthened the effect: Among those in the treatment group who were actually observed taking their medication on a daily basis, the risk of contracting HIV was actually 56 percent lower than it was in the control group.

PrEP with tenofovir was already known to be effective at reducing sexual transmission of HIV in studies conducted with heterosexuals and men who have sex with men, but this was the first study to show its effectiveness in people who inject drugs. (The latter group is at heightened risk for contracting HIV sexually as well as through injecting drug use.)

Last year the FDA approved tenofovir in combination with another drug, emtricitabine (Truvada), as a prophylactic measure for groups at risk for contracting HIV sexually. Based on the Bangkok study, the CDC has now recommended that people who inject drugs also consider taking this drug combination to decrease their likelihood of contracting HIV.

The challenge of reaching people who inject drugs with testing and other needed services remains, of course. But the new expanded possibilities of antiretroviral drugs as prophylactics for high-risk populations represents one more important tool in a multi-pronged approach to achieving a world free of AIDS.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to HIV infection in the modified intention-to-treat population. The graph shows cumulative probability of HIV infection (percent; y-axis) over time from the beginning of the study (months since randomization, from 0 to 84; x-axis) for the placebo group and the group receiving tenofovir. The cumulative probability of HIV infection in the two conditions diverges after 36 months, rising about twice as steeply thereafter in the placebo group versus the tenofovir group. By 84 months, the incidence of HIV was 0.35 per 100 person-years in the tenofovir group and 0.68 per 100 person-years in the placebo group, representing a 49% reduction in HIV incidence in those treated with tenofovir.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to HIV infection in the modified intention-to-treat population. The graph shows cumulative probability of HIV infection (percent; y-axis) over time from the beginning of the study (months since randomization, from 0 to 84; x-axis) for the placebo group and the group receiving tenofovir. The cumulative probability of HIV infection in the two conditions diverges after 36 months, rising about twice as steeply thereafter in the placebo group versus the tenofovir group. By 84 months, the incidence of HIV was 0.35 per 100 person-years in the tenofovir group and 0.68 per 100 person-years in the placebo group, representing a 49% reduction in HIV incidence in those treated with tenofovir.