Every year, the NIDA-supported Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan asks 8th, 10th, and 12th graders across the country about their current and past drug use and their attitudes toward drug use, providing us with an invaluable barometer of youth drug trends from year to year. The results of the 2013 MTF survey , which were released today, included some good news—such as 5-year declines in the abuse of prescription opioids, alcohol, and cigarettes by teens. Use of synthetic marijuana (K2/spice), Vicodin, and salvia by 12th graders is also down from last year, as is use of inhalants by 8th graders. It is gratifying to see these statistics, as well as the continued low levels of abuse of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine by students in the survey.

But there were also reasons to be concerned. The survey showed a 4-year increase in the nonmedical use of Adderall by 12th-graders; students may abuse prescription stimulants in the mistaken belief that they will boost cognitive performance and help their grades, or simply to get high. And one of the most worrisome trends in the MTF concerns teens’ attitudes toward marijuana use. Less than 40 percent of high school seniors this year said they think regular marijuana users risk harming themselves (physically or in other ways), down almost five percentage points from last year; in fact, the perception by 12th-graders that regular marijuana may be dangerous is the lowest it has been since 1978.

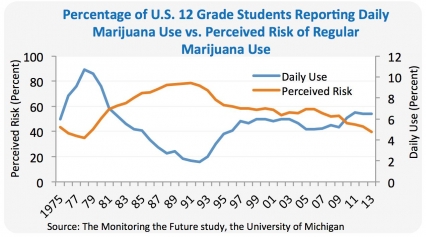

The plot below provides a striking teaching point: Over the 3 decades of MTF’s existence, the fluctuating perception of marijuana’s risks by teens has exactly mirrored how much they have used the drug. The public conversation about marijuana’s purported therapeutic benefits is likely contributing to the common impression that the drug is not harmful. Yet most of what we know from research in animals and humans points to significant cognitive impairment and negative impacts on brain development and various measures of life satisfaction, success, and achievement when marijuana is used heavily, especially during adolescence.

There are at least two ways in which the problem of teen marijuana use could actually be worse than the MTF numbers indicate. First, the survey does not take into account the rising potency of marijuana from year to year. In 1990, marijuana in the United States averaged 3.35 percent THC (the main psychoactive ingredient in the marijuana plant); today’s average street potency is well over four times that, at almost 15 percent. Although it is possible that users today may moderate their THC intake by smoking less on a given occasion, it is likely the MTF use trends don’t fully reflect the magnitude of the impact marijuana may be having on the brains of today’s teenagers. For example, the participants in the large-scale New Zealand study published last year who had lost an average of 8 IQ points after using marijuana heavily as teenagers would have turned 18 in 1990 or 1991—when marijuana potency in New Zealand was comparable to what it was in the U.S. at the time (between 1 and 5 percent). Would they have lost more IQ points had marijuana been more potent? Only further research can answer that question.

Second, it is important to remember that the MTF only surveys adolescents who are in school. Although the nationwide graduation rate is climbing, fully a quarter of the class of 2010 did not finish high school, and heavy marijuana use is linked to school dropout. The 6.5 percent of 12th graders who reported in the MTF that they use marijuana daily is thus likely to be less than the percentage of all American 17- and 18-year-olds using marijuana on a daily or near-daily basis.

The annual MTF results give us crucial information about where to concentrate our efforts at prevention. While America’s teens do seem to be hearing some of our messages—for instance, that synthetic marijuana could easily land them in an emergency room—we clearly need to do more to impress upon them that the harms of marijuana, although less immediate and less obvious than those of some other drugs, are no less serious: Among others, it can negatively affect a person’s ability to learn and, in turn, their academic performance. This is an important reason for teens to steer clear of marijuana while their brains are still maturing.