Combating the epidemic of opioid abuse—including prescription painkillers and, increasingly, heroin—requires a multi-pronged approach that involves reducing drug diversion, expanding delivery of existing treatments (including medication-assisted treatments), and development of new medications for pain that can augment our existing treatment arsenal. But another crucial component we must not forget is that people who abuse or are addicted to opioids need to be kept alive long enough that they can be treated successfully. In this, the drug naloxone has a large potential role to play.

© M intropin

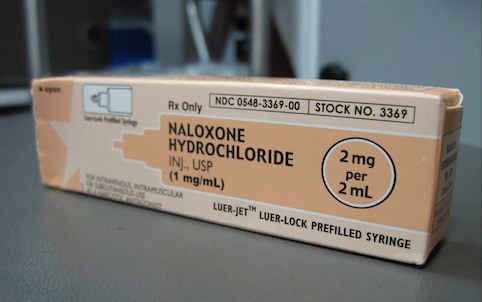

© M intropin Naloxone is an opioid antagonist—meaning that it binds to opioid receptors and can reverse or block the effects of other opioids. It can very quickly restore normal respiration to a person whose breathing has slowed or stopped as a result of abusing heroin or prescription opioids, or accidentally ingesting too much pain medication. Naloxone is widely used by emergency medical personnel and other first responders for this purpose. Unfortunately, by the time a person having an overdose is reached and treated, it is often too late. To solve this problem, several experimental overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs have issued naloxone directly to opioid users and their friends or loved ones, or other potential bystanders, along with brief training in how to use these emergency kits. Such programs have been shown to be an effective, as well as cost-effective, way of saving lives.

For example, a Massachusetts OEND program that began in 2006, during a growing overdose epidemic in that state, significantly reduced overdose deaths in the 19 communities that implemented it. As of 2010, the CDC reported that lay-distributed naloxone had prevented more than 10,000 overdose deaths nationwide since 1996. So far, 17 states have passed laws allowing for wider prescription of naloxone to those in a position to help prevent overdose fatalities. These laws help put the life-saving drug not only in the hands of family members and friends of opioid-addicted persons but also a wider array of emergency personnel, such as police and firefighters.

Naloxone is currently only FDA approved in an injectable formulation. To facilitate ease of use, many OEND programs use syringes fitted with an atomizer to enable the drug to be sprayed into the nose. NIDA and other agencies are working with the FDA and drug manufacturers to support the development of an intranasal formulation that would match the pharmacokinetics (i.e., how much and how rapidly the drug gets into the body) of the injectable version.

Over 15,500 Americans died from an overdose involving prescription painkillers in 2009—more than from all other drugs combined--and we are now seeing indicators of a rise in heroin overdose deaths as well. If we are to reverse these terrible trends, we need to do all we can to ensure that emergency personnel as well as at-risk opioid users and their loved ones have access to tools like naloxone that may save people’s lives in the event of overdose.

[Since this blog was posted in 2014, the FDA has approved other naloxone formulations, including a nasal spray (Narcan) and an easy-to-use autoinjector (Evzio).]