Diversity enriches any workforce, and that is especially true of science. People with different backgrounds and experiences may think in different ways, produce different ideas and insights, and approach scientific questions from different angles. Unfortunately, substance abuse and addiction research shares with the health sciences in general a lack of investigators from underrepresented populations. Across the NIH, White and Asian researchers continue to receive a disproportionate number of research project grants compared to other racial and ethnic groups.

Career Level Disparities in Neuroscience Programs for URMs

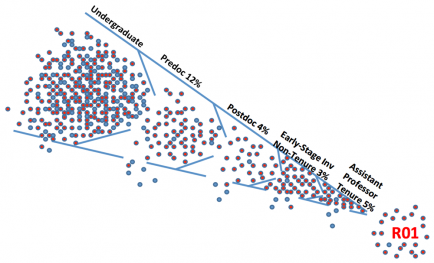

Higher attrition rate for underrepresented minorities (URMs) compared to Whites at all levels, but is most pronounced at the graduate school level. Report of the Advisory Committee to the NIH Director Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce, 2012

Higher attrition rate for underrepresented minorities (URMs) compared to Whites at all levels, but is most pronounced at the graduate school level. Report of the Advisory Committee to the NIH Director Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce, 2012There are no doubt many complex reasons for this, but an examination of the educational and career “pipeline” leading to the receipt of an NIH research project grant (R01) clearly indicates that attrition is a crucial factor and is higher for underrepresented minorities (URMs) than for Whites at each stage, from high school/undergraduate through graduate, postdoctoral, and early career levels (see figure). Leakage from the pipeline is especially pronounced in graduate school. The end result: In 2010, only 3.5 percent of principle investigators on NIH research project grants were Hispanic or Latino, only 1.1 percent were African American, and just 0.2 percent were Native American. A 2011 study in Science also found that, after controlling for numerous variables like educational background, country of origin, training, and publication record, African-American applicants were still 10 percent less likely than White applicants to be granted a research award by NIH.

The racial disparity is stark in medical schools, where just 4.1 percent of full-time faculty were reported to be Hispanic or Latino in 2010, just 2.9 percent were African American, and just 0.1 percent were Native American. The situation is similar in neuroscience programs, from which NIDA draws heavily for much of its basic science workforce: According to a survey by the Society for Neuroscience, in 2011, just 4 percent of postdoctoral trainees and 5 percent of tenure-track faculty at neuroscience programs were African-American, Hispanic, or Native American.

New measures to boost diversity in health sciences research are long overdue. To begin to address the issue across NIH, Francis Collins recently hired a Chief Officer for Scientific Workforce Diversity, and the NIH Common Fund established the “Enhancing the Diversity of the NIH-Funded Workforce” program. For our part, NIDA’s Office of Diversity and Health Disparities will be working closely with our extramural research community to find ways of attracting talented scientists from underrepresented minority populations to the field of substance abuse research. Our External Diversity Networks (formerly External Diversity Work Groups) will play a key role in this mission.

NIDA’s four External Diversity Networks consist of established scholars who are invited to advise on the research and scientific needs of African Americans, Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and American Indians/Alaska Natives. In the past, their focus has been to ensure that NIDA’s portfolio adequately addresses health disparities, but increasingly these networks will be called upon to help attract new researchers from their respective populations and increase the competitiveness of grant proposals by minority scientists in training. This will be done through activities such as grant writing workshops, scientific symposia, and special training and mentoring programs. For instance, I would like to create diversity mentoring networks, in which invited postdocs and early investigators who have not yet obtained NIH funding can be matched with mentors who have successful grant-writing experience and given opportunities to receive feedback on grant applications.

When it comes to clinical and epidemiological study populations, NIDA’s research has always been diverse: Our portfolio by default addresses minority groups who, unfortunately, are often those most affected by consequences and problems related to drug use, including health problems such as HIV/AIDS. But I look forward to doing more to increase diversity on the researcher side, expanding the pool of investigators doing this crucial work so that we better draw on the creativity and ingenuity of our diverse population.