A guest blog by Bill Williams

In 2012, New Yorkers Bill Williams and Margot Head lost their son Will to an overdose, after a long hard fight against his addiction. He was only 24. Bill—a freelance director, writer, and acting teacher—began to use his writing talents to get past his sorrow and speak up about the many challenges families face when dealing with this tragic illness—in his words “to remove the stain of shame surrounding this disease.” His family’s story is compelling, and this year I asked Bill and Margot to speak to the NIDA staff during our annual Employee Recognition ceremony. I have also asked him to share his thoughts in a guest blog, as a reminder of the devastating and incomprehensible experiences faced by families who are fighting the disease of addiction.

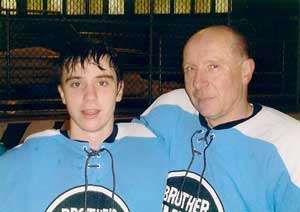

Photo by Michael LoPrioreBill Williams and his son William Head Williams

Photo by Michael LoPrioreBill Williams and his son William Head WilliamsA friend of our son, William, was on the phone, asking if Will was around. I went into our living room where he was watching television. He appeared to have dozed off. I told his friend I’d have Will him call back. I went back into the living room. Will hadn’t dozed off. He’d overdosed: slumped over, an uncomprehending glaze in his eyes, a needle on the floor at his feet. A frantic 911 call: attempting to revive him, unlocking our front door for the emergency responders, moving him to the floor to better position him, searching for a pulse, all while trying to follow instructions and give a status report to the 911 operator. His heart had stopped by the time EMS arrived.

His heartbeat restored, he was rushed to the hospital. There we spent six weeks at his bedside watching for glimmers of response and waiting for a recovery that never arrived. The time came when we had to accept that, at best, William would be in a persistent vegetative state. Those six weeks left us determined William’s life and death would not be in vain. We opted for organ donation and were with him in the operating room when he was removed from life support. He did not expire within the brief but necessary time frame that allows successful donation.

Our next decision, to make an anatomical donation of William’s body to Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, was praised by the interns and residents who had tended to him. They reassured us there was so much to be learned from such a donation, that he and we would indeed help save the lives of others, perhaps even more lives than via organ transplants

Even that donation was a struggle. We are deeply grateful to the resident who immediately devoted much time and effort to the task of convincing the Medical Examiner’s office no autopsy was necessary, as a donation requires an intact body. The College of Physicians and Surgeons needed some persuasion as well, as the gift of someone so young is rare. First year medical students studying anatomy would find working on a contemporary unsettling.

Whether we were aware of it or not, those six weeks at William’s bedside gave us the chance to weigh the opportunity to do something constructive in relation to the shame and silence the stigma of addiction imposes upon families. As William deteriorated, our thoughts and plans on what to do and how to go about it evolved. A luxury most families of those lost to addiction do not have.

What can we learn from the tragedy of drug deaths? We can begin with clear and precise autopsy reports. In our case an immediate cause was “complications of acute heroin intoxication” due to “acute and chronic substance abuse.” No mystery there. But the language used to describe an opioid death remains the choice of individual physicians. “Narcotics overdose” and “opiate toxicity” are insufficient. We need a consistent, congruent reporting language on a national scale.

What do we do about family doctors and coroners who may do a family a “favor” in obscuring the cause of death? How many “heart failures,” for example, cover up deaths due to drugs—not only of people in their late teens and early twenties, but also elderly people addicted to prescription opioids? The statistics on heroin and opioid deaths are faulty because of reporting that is incomplete, undisclosed, not tracked, or fails to ask the proper questions. The stigma surrounding the disease inhibits an accurate understanding of the scope of the disease.

We need comprehensive reporting on drug deaths. What drug(s) was/were involved? What combinations? What could we learn by asking about a drug user’s use history and medical history prior to his or her death? What collateral complications or causes were involved? Does murdered by a dealer count as a drug death? It happens. We could learn so much if we required not only uniform descriptions for drug deaths, but also a standardized set of comprehensive questions to gather useful information.

We don’t need to stop at statistics. What might we learn from standardized autopsies performed on addiction deaths? Is there a place where a family such as ours, inclined to make an anatomical donation, might donate a body specifically for research into addiction. Is there a brain bank devoted to the study of addiction? If so, let people know. If not, why not? We have such banks for sports-related brain injuries and other brain research.

In short, we need to be consistent, congruent, and comprehensive when we talk about addiction deaths. The dead don’t talk much. Or maybe they do and we need to learn to listen better.

More from Bill Williams at http://billwilliamsblog.blogspot.com/