In the face of worldwide increases in the use of MDMA, or ecstasy, particularly among teens and young adults, NIDA convened an international array of scientists at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, in July for a conference on "MDMA/Ecstasy Research: Advances, Challenges, Future Directions." MDMA researchers from Australia, Europe, and all regions of the United States detailed the latest findings on patterns and trends of MDMA abuse, its complex acute effects on the brain and behavior, and the possible long-term consequences of its use.

In opening remarks, Dr. Glen Hanson, director of NIDA's Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Research, noted the tremendous interest of the scientific community and the general public in MDMA and its effects. The sold-out conference drew an audience of 565 people with a broad range of interests and perspectives. They included scientists, drug abuse prevention and treatment practitioners, clinicians, educators, high school counselors, and representatives from Federal and local public health departments and agencies.

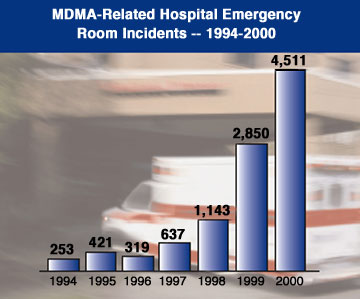

A public health perspective on MDMA by James N. Hall, of the Up Front Drug Information Center in Miami, Florida, provided a sharp contrast to the prevailing public view of MDMA as an innocuous drug. MDMA use began to expand rapidly in the United States in 1996 with "more pills going to younger populations," Mr. Hall said. This upsurge in use led to an increase in drug-related problems. For example, MDMA-related hospital emergency room incidents increased from 253 in 1994 to 4,511 in 2000, according to recent data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's Drug Abuse Warning Network. "Most of these emergency room mentions are multiple-drug cases," Mr. Hall said, "as polydrug use has become the norm."

The common practice of using MDMA in conjunction with other drugs was just one of several recurring themes sounded during a conference session on current trends and patterns of MDMA use. Other significant themes were:

- MDMA now is being used in urban, suburban, and rural areas throughout the country;

- MDMA continues to be used in its traditional settings of all-night dance parties, called "raves," and nightclubs; use also is common now on college campuses and at small group gatherings, such as house parties;

- MDMA is used by all ages but still mainly by adolescents and young adults; use has increased sharply in this population in recent years;

- MDMA users are predominantly white, but ethnically and racially diverse groups of people are now using the drug (see "The Many Faces of MDMA Use Challenge Drug Abuse Prevention"); and

- MDMA's euphoric effects can lead to unplanned or unwanted sexual contact that increases the risk of transmitting HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases.

Researchers present the latest findings at NIDA's international conference on MDMA/ecstasy abuse.

Researchers present the latest findings at NIDA's international conference on MDMA/ecstasy abuse.Acute Effects of MDMA

A session on MDMA's acute effects presented the latest findings on how the drug works in the brain and to produce its perceptual and physiological impact. The session explored the interaction of underlying biological and behavioral factors and mechanisms that may contribute to the possibly harmful effects of MDMA use.

Animal studies have indicated that MDMA increases extracellular levels of the chemical messengers serotonin and dopamine. In laboratory studies to understand how these increases affect humans, Dr. Manuel Tancer of Wayne State University in Detroit asked participants to compare MDMA's effects to those produced by compounds that stimulate serotonin alone and dopamine alone. MDMA's effects were reported to resemble some features of both compounds, noted Dr. Tancer. This indicates that both the dopamine and serotonin systems play a role in producing MDMA's subjective effects in humans.

MDMA also has powerful acute physiological effects in humans that increase with larger doses, according to several presentations. MDMA's cardiovascular effects include large increases in blood pressure, heart rate, and myocardial oxygen consumption, noted Dr. John Mendelson of the University of California, San Francisco. MDMA's elevations of heart rate and blood pressure were comparable to those produced by a maximal dose of dobutamine, a cardiovascular stimulant used in stress tests to evaluate patients for coronary artery disease, he said. However, unlike dobutamine, MDMA did not increase the heart's pumping efficiency. Thus, MDMA-induced heart rate and blood pressure increases may lead to an unexpectedly large increase in myocardial oxygen consumption, which can increase the risk for a cardiovascular catastrophe in people with preexisting heart disease, he said.

Even small increases in MDMA dose can greatly reduce the 's ability to metabolize the drug. This means MDMA is not processed and removed from the quickly and remains active for longer periods. "As a result, plasma levels of the drug and concomitant increases in toxicity may rise dramatically when users take multiple doses over brief time periods. Increased toxic effects can lead to harmful reactions such as dehydration, hyperthermia, and seizures," Dr. Mendelson said. Drugs such as methamphetamine that are commonly abused in conjunction with MDMA also may increase the cardiovascular effects of MDMA, he said.

Dr. Glen Hanson, director of NIDA's Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Research, describes some of MDMA's toxic effects on different brain regions.

Dr. Glen Hanson, director of NIDA's Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Research, describes some of MDMA's toxic effects on different brain regions.MDMA tablets often contain other drugs, such as ephedrine, a stimulant, and dextromethorphan, a cough suppressant that has PCP-like effects at high doses, that also can increase its harmful effects. In addition, drugs sold as MDMA may actually be substances that are much more dangerous, according to Dr. Rodney Irvine of the University of Adelaide in Australia. For example, the hallucinogen PMA (4-methoxyamphetamine), which is similar in some respects to MDMA, has even more severe toxic effects on the cardiovascular system, particularly as dosage increases. The drug has been sold as MDMA in Australia and has been associated with a number of deaths. PMA is now being distributed in the United States and has been linked to deaths in Chicago and Central Florida, according to the Federal Drug Enforcement Administration.

Long-Term Effects of MDMA

During the second day of the conference, researchers from the United States and other countries described current investigations of ecstasy's long-term effects. Introducing the day's program, Dr. Hanson summarized the mechanisms thought to be responsible for MDMA's toxic effects on the brain's serotonin system. In tests of learning and memory, he noted, MDMA users perform more poorly than nonusers on tasks associated with brain regions affected by MDMA. Higher doses of MDMA appear to be associated with more profound effects, and the consequences may be long-lasting.

Dr. Charles Vorhees of Children's Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, has found that, in rats, exposure to MDMA during a period of brain development that corresponds to human brain development during the trimester before birth is associated with learning deficits that last into adulthood. "The impairment, which affects the rate at which the animals learn new tasks, increases in severity as the dose of MDMA increases and is more pronounced as the tasks become more complex," Dr. Vorhees said.

These findings of MDMA's effects on brain development are limited to studies involving rats, but there is a growing of research suggesting that-in adult primates-MDMA can cause long-lasting damage. At the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Drs. Una McCann, George Ricaurte, and other investigators have found that exposure to MDMA is associated with damage to brain cells that release serotonin; this damage persists for at least 7 years in nonhuman primates. In humans, the researchers have found that MDMA use is associated with verbal and visual memory problems in individuals who have not used the drug for at least 2 weeks. "We see a relationship between the dose of MDMA and the severity of the effects. In animals, MDMA-induced damage is extensive and long-lasting and we do not yet know if it is reversible," Dr. Ricaurte said. "A person who takes enough of the drug to feel its effects is taking enough to be at serious risk of similar damage to the brain and to memory and learning."

MDMA disrupts brain processes that use the amino acid tryptophan to make the neurotransmitter serotonin, which affects memory and mood. Five hours after drinking a tryptophan supplement, ex-users of MDMA showed greater elevations of their blood tryptophan levels than did current users or nonusers, indicating that less of the amino acid had been converted to serotonin.

MDMA disrupts brain processes that use the amino acid tryptophan to make the neurotransmitter serotonin, which affects memory and mood. Five hours after drinking a tryptophan supplement, ex-users of MDMA showed greater elevations of their blood tryptophan levels than did current users or nonusers, indicating that less of the amino acid had been converted to serotonin.Dr. Linda Chang, a scientist at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York, reported on research using brain imaging techniques to evaluate the effects of occasional use of MDMA. She and her colleagues Dr. Charles Grob and Dr. Russell Poland at the University of California, Los Angeles, used single photon emission computed tomography to evaluate blood flow to the brain - which is regulated in part by serotonin - in 21 MDMA users who had taken the drug at least 6 times per year for more than 1 year (on average, a total of 75 times), but had not used the drug in at least 2 weeks (4 months average abstinence). The participants then were given MDMA in two sessions over the course of a week. Two weeks later, brain images showed decreased blood flow compared to the earlier images. The decrease was greater in those individuals who had higher total use of the drug.

MDMA Research in Europe

The popularity of MDMA as a "club drug" began in Europe in the late 1980s - roughly 5 years earlier than in the United States - and researchers there have studied the drug's effects in populations with a longer history of drug use. In Great Britain and Germany researchers have found that MDMA users - and even former users who have not taken the drug for at least 6 months - perform more poorly on some tests of memory and learning than do nonusers. MDMA also is associated with psychological problems such as anxiety and depression, this research suggests.

The airplane figure at top is exactly matched by only one of six similar figures below. When asked to find the correct match, current and ex-users of MDMA made quicker choices and made more wrong choices before identifying the correct match than participants who used drugs other than MDMA or who used no drugs at all.

The airplane figure at top is exactly matched by only one of six similar figures below. When asked to find the correct match, current and ex-users of MDMA made quicker choices and made more wrong choices before identifying the correct match than participants who used drugs other than MDMA or who used no drugs at all.The learning and memory functions that appear to be impaired by MDMA in animal and human studies are associated with the brain's serotonin system. The specific effects of MDMA can be evaluated directly in animal studies, but in humans nearly all MDMA users also use other drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. In an effort to more fully understand how MDMA affects polydrug users, Dr. Valerie Curran and her colleagues at University College London investigated the effect of MDMA use on the 's ability to use tryptophan, an amino acid that is one of the chemical building blocks for serotonin. The research involved three groups of polydrug users: some were current MDMA users, some had stopped using the drug, and some had never used it.

The researchers first measured blood levels of tryptophan and found that current and ex-users of MDMA had higher blood levels than did nonusers and that the levels were elevated in proportion to the total amount of drug the participants had used. The investigators then gave participants drinks that contained augmented amounts of tryptophan in addition to all other necessary amino acids. Five hours later they measured blood levels of the amino acid. Ex-users of MDMA showed far higher levels of tryptophan in their blood than did nonusers or current users, Dr. Curran said. "Tryptophan should cross the blood-brain barrier to be incorporated into the biosynthesis of serotonin, but in ex-users, significantly higher levels of tryptophan remained in the blood," she said.

In memory tests, current users did more poorly than did nonusers; ex-users-who had not taken MDMA for an average of 2 years-had the poorest performance. The reason for such poor performance among the ex-users is uncertain, Dr. Curran said. One possibility is that these were people who developed particularly severe adverse effects and quit using the drug because of them. "Whatever the reason, there is a clear correlation between a biological marker (blood levels of tryptophan), a functional deficit (poor performance on tests of memory), and the total dosage and length of time these people used MDMA before they stopped," Dr. Curran said.

Dr. Euphrosyne Gouzoulis-Mayfrank of the University of Technology in Aachen, Germany, also described research involving MDMA's effects on polydrug users. She and her colleagues compared cognitive performance in three groups of participants age 18 to 30. One group included MDMA users with a typical pattern of recreational use (at least twice per month within the preceding 2 years) who also used marijuana (at least once per month over a 6-month period), a second group who did not use MDMA but whose marijuana use roughly matched that of the MDMA users, and a third group who had never used either drug. "Ecstasy users showed no impairment in tests of alertness," she said, "but performed worse than one or both control groups in more complex tasks of attention, in memory and learning tasks, and in tasks reflecting aspects of general intelligence."

Dr. Michael Morgan of the University of Sussex in Great Britain described research that suggests a relationship between marijuana use, MDMA use, and psychological problems and memory deficits. Dr. Morgan and his colleagues studied the effects among groups of current MDMA users, ex-users, polydrug users who did not use MDMA, and participants who had never used drugs.

The researchers found that the psychological measures were more closely associated in the polydrug population with current marijuana use than with past MDMA use. "Overall, however, current and ex-users of MDMA have dramatically higher measures of psychopathology such as impulsivity than nonusers," Dr. Morgan said. Like Dr. Curran, Dr. Morgan found cognitive deficits associated with rates of past MDMA use. In tests of memory, both current and ex-users performed more poorly than nonusers. He also found that on some tests ex-users performed worse than did current users, although he noted that the reasons for poorer performance by ex-users could not clearly be linked exclusively to MDMA use. "Nonetheless, as a practical matter, ex-users show massively impaired memory. Not only had they not recovered, they were actually worse than current users," Dr. Morgan said.

In tests of MDMA effects on memory, ex-users and current users performed worse than participants who used drugs other than MDMA or used no drugs. Ex-users, in particular, showed greatly impaired memory.

In tests of MDMA effects on memory, ex-users and current users performed worse than participants who used drugs other than MDMA or used no drugs. Ex-users, in particular, showed greatly impaired memory.