Statement for the Record

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to present scientific findings about Ecstasy or MDMA. I am Dr. Glen Hanson, the Acting Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), a component of the National Institutes of Health.

As NIH is the world's leading supporter of research on the health aspects of all drugs of abuse, I would like to share with you today the latest scientific findings about MDMA and the impact it can have on the health and well-being of individuals and communities.

Let me begin by stating that there is substantial scientific evidence that proves that 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, which is frequently referred to by the acronym MDMA and known on the street as "Ecstasy," has substantial risk associated with its use. It is not benign, like some of its users and even a very small minority of researchers have proclaimed. MDMA can produce both short- and long-term physiological and psychological consequences that can be detrimental to an individual's health. There is accumulating animal and human data suggesting that chronic abuse may produce long-lasting neurotoxic effects in the brain.

Pharmacologically, MDMA has both stimulant and hallucinogenic properties. While MDMA rarely causes overt hallucinations, many people report distorted time and exaggerated sensory perception while under the influence of the drug. It also causes an amphetamine-like hyperactivity and euphoria in people, and like other stimulants, it appears to have the ability to cause addiction. A recent NIDA-supported study in Human Psychopharmacology found that in 173 adolescents and young adults, of the 52 users who had reported using MDMA, almost 60 percent met the diagnostic criteria for abuse and dependence, and 43 percent met the criteria for MDMA dependence alone.

Use of MDMA increases heart rate, blood pressure and can disable the body's ability to regulate its own temperature. Because of its stimulant properties, when it is used in club or dance settings, it stimulates users to dance vigorously for extended periods, but can also lead to dangerous rises in body temperature, referred to as hyperthermia, as well as dehydration, hypertension, and even heart or kidney failure in particularly susceptible people.

MDMA is typically available in capsule or tablet form and is usually taken orally, although there are documented cases suggesting that more and more frequently it is being administered by other routes, including injection and snorting. MDMA's acute effects typically last from three to six hours depending on the dosage, with the reported average dose of MDMA consumed by a typical user being between one and two tablets, with each containing approximately 60-120 mg of MDMA. However, much higher doses of five tablets and greater are not unusual. MDMA appears to be well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, and after administration peak levels are reached in about an hour.

It is known that drugs that are sold to individuals as "Ecstasy" tablets frequently contain not only MDMA, but other drugs or drug combinations that can be harmful. Adulterants found in MDMA tablets purchased on the street by researchers include methamphetamine, caffeine, the cough suppressant dextromethorphan, an over the counter cough suppressant that has PCP-like effects at high doses, the diet drug ephedrine, and cocaine. Also, like with other drugs of abuse, MDMA is rarely used alone. It is not uncommon for users to mix MDMA with alcohol, Viagra, or GHB or to "bump" and take sequential doses of a drug or drugs when the initial dose begins to fade. This has been confirmed by both treatment reports and medical examiner reports. Because of these drug combinations, it is difficult to anticipate with certainty all the potential medical consequences that can result from the use of MDMA. These drug combinations can also make it challenging to determine the precise role of MDMA in adverse reactions in recreational users.

MDMA in its true form works in the brain by increasing the activity levels of at least three neurotransmitters (the chemical messengers of brain cells): serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Like amphetamines, MDMA causes these neurotransmitters to be released from their storage sites in neurons resulting in increased brain activity. Compared to the very potent stimulant, methamphetamine, MDMA causes greater serotonin release and somewhat lesser dopamine release. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that plays an important role in regulation of mood, sleep, pain, emotion, appetite, and other behaviors. By releasing large amounts of serotonin and also interfering with its synthesis, MDMA causes the brain to become significantly depleted of this important neurotransmitter. As a result, it takes the human brain time to rebuild its serotonin levels. For people who take MDMA at moderate to high doses, depletion of serotonin may be long-term. These persistent deficits in serotonin are likely responsible for many of the persistent behavioral effects that the user experiences.

There is a growing body of evidence that associates this serotonin loss in heavy MDMA users to confusion, depression, sleep problems, persistent elevation of anxiety, aggressive and impulsive behavior and selective impairment of some working memory and attention processes.

I will quickly highlight one study that demonstrates how MDMA has been shown to affect impulsivity. We know that many drugs of abuse can interfere with judgment or reduce inhibitions about risk taking behaviors, and MDMA is no exception. For example, it can make an individual more vulnerable to risky sexual behavior, increasing the chance of contracting HIV or other sexually transmitted diseases. We also know from new research that current and former users of MDMA have dramatically higher measures of psychopathology such as impulsivity than nonusers. In a recent study, researchers compared four groups: current MDMA users, former MDMA users who had abstained from using the drug for an average of 2 years, polydrug users who had never taken MDMA, and individuals who reportedly never used drugs. Both current and former MDMA users exhibited higher measures of psychopathology and impulsivity than non-users, and both groups also exhibited impaired working memory and recall performance compared with non-users, although only former users exhibited impaired delayed recall compared with polydrug users. These data suggest that psychological problems associated with heavy MDMA use often are not readily reversed even by prolonged abstinence. A number of other studies using standardized tests of mental abilities have consistently shown that repeated MDMA exposure is associated with significant impairments in visual and verbal memory.

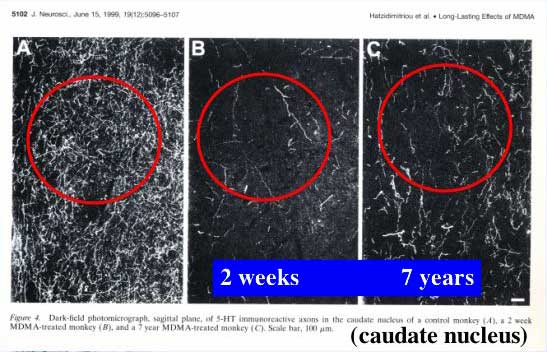

There is also ample evidence to show that MDMA damages brain cells. We know that even one dose of MDMA (10 mg/kg in rats) has the ability to decrease serotonin levels for up to 2 weeks. We are not certain if the brain has the full capacity to recover from MDMA, as I will discuss in findings depicted in Figure 1. The first panel in the figure shows a normal monkey brain. The monkeys were given 5 mg/kg of MDMA twice a day for four days. The researchers observed them two weeks, and then seven years, after the MDMA was administered. The middle section shows that two weeks after MDMA was given, there were pronounced reductions (83-95%) in serotonin axon density in all areas of the cerebral cortex. The last section shows that seven years after MDMA was given, there is still significant loss of serotonin fibers, though there appears to be some recovery. Investigators are trying to determine the relevance of such findings to humans and their functional significance, but already through the use of brain imaging technology, research has suggested that human MDMA abusers may have fewer serotonin-containing neuronal processes in the brain than non-users.

Figure 1 - Serotonin Levels in Monkeys After MDMA (5 mg/kg twice daily for 4 days)- Source: (Hatzidimitriou et al., J. Neurosci. 19 [1999] 5092)

Figure 1 - Serotonin Levels in Monkeys After MDMA (5 mg/kg twice daily for 4 days)- Source: (Hatzidimitriou et al., J. Neurosci. 19 [1999] 5092)Despite what we have come to know about the detrimental consequences of this drug, there are increasing numbers of students and young adults who continue to use MDMA. Several of our Nation's top monitoring mechanisms, including Monitoring the Future (MTF), NIDA's long-standing national survey of drug use among 8th, 10th and 12th graders, and our Community Epidemiology Work Group (CEWG), as well as recently released findings from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) National Household Survey on Drug Abuse and its Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Survey, report that MDMA continues to be a popular drug, particularly among young people.

Findings concerning MDMA use released earlier this month from the 2001 SAMHSA National Household Survey on Drug Abuse are not very encouraging. Initiation of MDMA use has been rising steadily since 1992. The survey reports that in 2001, 8.1 million Americans aged 12 or older were lifetime users of MDMA, up from 6.5 million in 2000. This means that around 1.6 million more people reported having tried MDMA at least once in their lifetime in 2001 than the previous year. Over three-quarters of a million people (786,000) reported in 2001 that they had used MDMA in the 30 days prior to the survey interview (current use).

NIDA's Monitoring the Future Study of drug abuse among adolescents in middle and high schools across the U.S. showed that in 2001, 5 percent of 8th-graders, 8 percent of 10th-graders, and 12 percent of 12th-graders had taken MDMA at least once in their lives. Although this does not represent a dramatic rise from the previous year, the rates are alarmingly high and have not declined following sizeable increases that started in 1998 among 10th and 12th graders, and in 1999 among 8th graders.

The encouraging news is that the proportion of 12th-graders surveyed who said that there is a great risk associated with experimenting with MDMA jumped from 38 percent in 2000 to 46 percent in 2001. This suggests that efforts to educate adolescents about the dangers of MDMA may be working and hopefully will have a positive effect on drug using behavior. Unfortunately, at the same time the perceived availability of MDMA increased sharply, the proportion of 12th-graders who thought they could get MDMA "fairly" or "very" easily jumped from 40 percent in 1999, to 51 percent in 2000, to 61 percent in 2001.

Significant MDMA use by students is occurring in more and more of the nation's schools and extends to many demographic subgroups. Among 12th-graders, for example, 10 percent of both Hispanic and white students reported using MDMA in the 12 months prior to the survey, compared to only 2 percent of African-Americans.

Ethnographic data from NIDA's CEWG released in June 2002 showed that MDMA is spreading beyond the young white populations frequenting "raves." For example, in Chicago, MDMA use has reportedly moved beyond the rave scene and can be found in most mainstream dance clubs and many house parties. Philadelphia also reports that MDMA demographics are changing, with MDMA being used increasingly by African-Americans and Hispanics, and by people in their thirties, not just teens. The group of epidemiologists, public health officials, and researchers who monitor emerging drug trends report that MDMA indicators of use continue to rise in almost all of the CEWG areas.

Also, new data from the 2001 Drug Abuse Warning Network released by SAMHSA in August showed that although there were no significant changes in emergency room mentions of MDMA from 2000 to 2001, the high incidence of MDMA mentions (5,542) in 2001 still reflects a disturbing pattern.

NIDA will continue to monitor the changing patterns and trends of MDMA and other drugs of abuse as part of its comprehensive research portfolio. NIDA will also continue to inform the public and policy makers about new science findings that will help us to understand the short- and long-term effects of this drug. It is hoped that such information will help to protect communities against the harmful consequences of this drug,

In closing, I would like to say that as someone who has spent more than 15 years of his research career examining the pharmacological and neurotoxic effects of psychostimulants, particularly MDMA, I am quite convinced that there is ample scientific evidence to show that MDMA damages brain cells, and I can confidently testify that MDMA is not a benign drug.

Thank you again for inviting the National Institute on Drug Abuse to be a part of this important subject. I will be happy to respond to any questions you may have.