The brain images produced by positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have broadened our understanding of drug addiction as a brain disease. Imaging techniques are providing new views of brain structure and activity, allowing researchers to watch small brain structures in minute detail and observe changes over fractions of seconds after drugs enter the brain's tissues.

Imaging technology also allows us to observe more indirect effects--how craving for drugs changes brain activity and the mechanisms by which inherited characteristics influence vulnerability to drug abuse or susceptibility to a drug's toxic or addictive properties. And with NIDA's continuing commitment to refinement of imaging techniques, our newfound scientific insight at the cellular level will merge with the broader focus that links the workings of an individual's brain to his or her behavior, emotion, reasoning, and decisionmaking.

PET imaging in drug abuse research relies on ligands--chemical compounds created in the laboratory that selectively attach to the same key sites (receptors) on brain cells as do drugs of abuse. Radioligands incorporate radioactive atoms that emit energy. PET "cameras" capture the energy these ligands emit when attached to target sites, and computers convert that energy to images that reveal the location and intensity of drug activity in the brain. NIDA-sponsored research at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York, led to the development of the first ligands designed to mimic cocaine in binding to one type of dopamine receptor, making it possible to trace the effect of cocaine on the brain's dopamine system. Other ligands allow researchers to study aspects of brain systems that involve other neurotransmitters, such as serotonin. At NIDA's Intramural Research Program (IRP), a multiyear effort has yielded a new ligand that binds to nicotine receptors. Researchers there have begun using this important new compound to study the activity of the brain's nicotine receptors in nonsmokers as well as smokers.

A broader selection of ligands that mimic more drugs and are specific to more aspects of neurotransmitter systems will allow researchers greater access to unexplored areas of the molecular realm where drugs act on the brain. For example, there are five types of dopamine receptors and more than a dozen receptors specific to nicotine, each with subtly different properties and functions. New ligands will improve our ability to use imaging techniques to observe and understand the activity of nicotine and other drugs in the brain and--just as important--potential medications to counter their effects.

To speed the development of new ligands, NIDA and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) have encouraged researchers to participate in National Cooperative Drug Discovery Groups. NIDA already has made awards to more than a dozen grantees, who are beginning work on this important research.

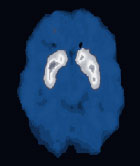

This PET image is formed from energy emitted by a radioactively labeled ligand that selectively attaches to dopamine D2 receptors on brain cells. PET studies can be used to evaluate and compare the distribution and density of receptor or transporter sites in drug abusers and nonusers.

This PET image is formed from energy emitted by a radioactively labeled ligand that selectively attaches to dopamine D2 receptors on brain cells. PET studies can be used to evaluate and compare the distribution and density of receptor or transporter sites in drug abusers and nonusers.Unlike PET, MRI does not rely on radioactive compounds to monitor a drug's activity in the brain. Because MRI does not expose study participants to the risks associated with radiation, researchers can conduct long-term studies, in repeated sessions lasting several hours, on the same person. At Brookhaven National Laboratory, NIDA-supported scientists using MRI have found evidence that methamphetamine abusers suffer abnormal blood flow in brain regions that control response times and short-term memory as long as 8 months after last using the drug (see "New Imaging Technology Confirms Earlier PET Scan Evidence: Methamphetamine Abuse Linked to Human Brain Damage"). At IRP, investigators are now using a newly installed functional MRI (fMRI) system that makes possible more comprehensive observation of drugs' effects on the functioning brain (see "New Technology Expands the Scope of NIDA's Intramural Brain Imaging Program").

In fMRI studies, investigators can watch drug-exposed and unexposed brains function during tasks involving reasoning and memory and compare brain activity with how well participants perform on the tasks. Scientists also can use fMRI to observe how the brain works in response to treatments that address the weaknesses revealed in tests of function and performance, thereby speeding development and evaluation of both pharmacological and behavioral treatments.

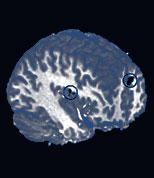

Functional magnetic resonance imaging shows activation of brain sites (circled) in cocaine addicts as they watch a film that induces cocaine craving.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging shows activation of brain sites (circled) in cocaine addicts as they watch a film that induces cocaine craving.In February, NIDA opened another area of brain imaging research when it announced a request for research projects to enhance understanding of the consequences of drug exposure, abuse, and addiction on the developing human brain--from prenatal exposure to the transition to adulthood. This research program (Neuroimaging the Effects of Drugs of Abuse on the Development of the Human Nervous System, RFA DA-04-002) will use a variety of imaging techniques--including PET, MRI, conventional optical imaging, and electroencephalography.

By comparing brain maturation processes in people who have and have not been exposed to drugs, this program will help us more clearly define how the timing and amount of drug exposure can disrupt brain development. NIDA's investment in brain imaging research is beginning to yield a more comprehensive picture of the disease of addiction. Our new initiatives will lead to a better understanding of the impact of drugs on the development and functioning of the human brain. And our continued investment in finding better chemical tools, techniques, and technology will provide increased understanding of drug abuse and, ultimately, a brighter outlook for drug abuse prevention and treatment.