Update: March 26, 2015

HHS announces steps to address opioid related deaths and dependence

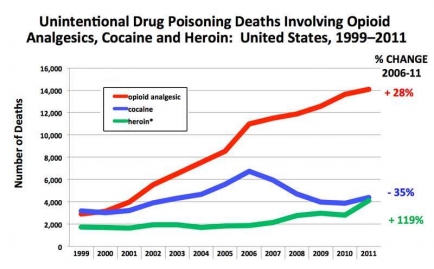

A striking new dimension of our nation’s ongoing opioid epidemic is the escalating number of deaths from heroin overdose. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 4,102 people died as an unintended consequence of heroin overdoses in 2011 (the most recent year for which data are available), compared to 2,789 deaths in 2010—a 47 percent increase in a single year. Heroin overdose deaths had risen somewhat over most of the preceding years (except for 2009-2010, when they actually declined), but the general upward trend had been more gradual, so these numbers come as a wake-up call.

For a few years, NIDA and other Federal partners have been sounding the alarm over the rise in heroin use, particularly among people with addictions to prescription opioids who switch to heroin because it is cheaper and easier to obtain. Half a million Americans are now addicted to heroin, and four out of five recent heroin initiates had previously used prescription opioids non-medically. Public light on this problem was shed earlier this year by the heroin-overdose death of Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who had reportedly begun using heroin after having developed a prescription drug addiction. But the scope and impact of the problem in our society is revealed in CDC’s population-wide numbers, which I discussed last week at a White House Summit on the opioid epidemic. In 2011, 11 Americans died every day from heroin overdose—nearly one person every 2 hours. (The same year, 14,091 people died from accidental overdoses of prescription opioids, also a figure that continues to rise steadily; see below.)

NIDA has actively pushed research on an easy-to-use intranasal formulation of naloxone, a drug that can save lives in the event of opioid overdose. We have also taken various measures to improve the education of clinicians in pain treatment and opioid prescribing and created resources (NIDAMED) to guide doctors in detecting and addressing prescription opioid abuse in their patients. But we and other government agencies must do much more to address one of the major drivers of the overdose epidemic: underlying opioid use disorders. Particularly, we must push for wider adoption and implementation of existing medication-assisted treatments (MATs) for opioid addiction.

Last month I coauthored a “Perspective” in the New England Journal of Medicine on the severe underutilization of these treatments, along with CDC Director Thomas R. Frieden, Pamela S. Hyde, Administrator of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and Stephen S. Cha of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The opioid antagonist naltrexone and maintenance therapies using the agonists buprenorphine or methadone have proven effective at helping patients recover from opioid addiction and at reducing overdoses. Moreover, all three treatments have been shown to improve social functioning, reduce criminal activity, and lessen the risk of transmitting infectious diseases like HIV. They are also cost-effective. But less than half of private-sector treatment programs have adopted MATs, and even in programs that offer them, only 34.4% of patients receive medications. Policy-related hindrances and limitations in the area of insurance coverage are among the barriers to wider MAT adoption, as is a shortage of physicians trained and qualified to deliver these medications. But another major barrier is attitudinal—namely, lingering beliefs (even among some staff and managers at opioid treatment clinics) that maintenance treatments simply replace one addiction with another. When maintenance treatment is offered, it is often at an insufficient dose or duration, leading to treatment failure and reinforcing the erroneous belief that medication is a poor approach.

Implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will help with some of the insurance coverage issues, but only by transcending old prejudices and misconceptions about opioid treatment (often rooted in stigma) can we ensure they are used and used effectively. We will not reduce the unacceptable numbers of overdose deaths from prescription opioids and, increasingly, heroin, without realizing that addiction—and failure to treat it—lies at the heart of the problem.

Source: National Center for Health Statistics/CDC, National Vital Statistics Report, Final death data for each calendar year (June 2014). * includes opium