The term acknowledges that addiction is a chronic but treatable medical condition involving changes to circuits involved in reward, stress, and self-control.

Photo by jkt_de

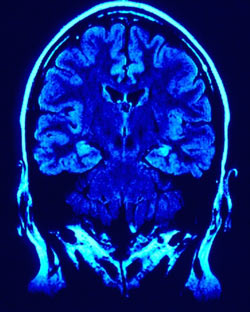

Photo by jkt_deAs a young scientist in the 1980s, I used then-new imaging technologies to look at the brains of people with drug addictions and, for comparison, people without drug problems. As we began to track and document these unique pictures of the brain, my colleagues and I realized that these images provided the first evidence in humans that there were changes in the brains of addicted individuals that could explain the compulsive nature of their drug taking. The changes were so stark that in some cases it was even possible to identify which people suffered from addiction just from looking at their brain images.

Alan Leshner, who was the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the time, immediately understood the implications of those findings, and it helped solidify the concept of addiction as a brain disease. Over the past three decades, a scientific consensus has emerged that addiction is a chronic but treatable medical condition involving changes to circuits involved in reward, stress, and self-control; this has helped researchers identify neurobiological abnormalities that can be targeted with therapeutic intervention. It is also leading to the creation of improved ways of delivering addiction treatments in the healthcare system, and it has reduced stigma.

Informed Americans no longer view addiction as a moral failing, and more and more policymakers are recognizing that punishment is an ineffective and inappropriate tool for addressing a person’s drug problems. Treatment is what is needed.

Fortunately, effective medications are available to help in the treatment of opioid use disorders. Medications cannot take the place of an individual’s willpower, but they aid addicted individuals in resisting the constant challenges to their resolve; they have been shown in study after study to reduce illicit drug use and its consequences. They save lives.

Yet the medical model of addiction as a brain disorder or disease has its vocal critics. Some claim that viewing addiction this way minimizes its important social and environmental causes, as though saying addiction is a disorder of brain circuits means that social stresses like loneliness, poverty, violence, and other psychological and environmental factors do not play an important role. In fact, the dominant theoretical framework in addiction science today is the biopsychosocial framework, which recognizes the complex interactions between biology, behavior, and environment.

There are neurobiological substrates for everything we think, feel, and do; and the structure and function of the brain are shaped by environments and behaviors, as well as by genetics, hormones, age, and other biological factors. It is the complex interactions among these factors that underlie disorders like addiction as well as the ability to recover from them. Understanding the ways social and economic deprivation raise the risks for drug use and its consequences is central to prevention science and is a crucial part of the biopsychosocial framework; so is learning how to foster resilience through prevention interventions that foster more healthy family, school, and community environments.

Critics of the brain disorder model also sometimes argue that it places too much emphasis on reward and self-control circuits in the brain, overlooking the crucial role played by learning. They suggest that addiction is not fundamentally different from other experiences that redirect our basic motivational systems and consequently “change the brain.” The example of falling in love is sometimes cited. Love does have some similarities with addiction. As discussed by Maia Szalavitz in Unbroken Brain, it is in the grip of love—whether romantic love or love for a child—that people may forego other healthy aims, endure hardships, break the law, or otherwise go to the ends of the earth to be with and protect the object of their affection.

Within the brain-disorder model, the neuroplasticity that underlies learning is fundamental. Our reward and self-control circuits evolved precisely to enable us to discover new, important, healthy rewards, remember them, and pursue them single-mindedly; drugs are sometimes said to “hijack” those circuits.

Metaphors illuminate complexities at the cost of concealing subtleties, but the metaphor of hijacking remains pretty apt: The highly potent drugs currently claiming so many lives, such as heroin and fentanyl, did not exist for most of our evolutionary history. They exert their effects on sensitive brain circuitry that has been fine-tuned over millions of years to reinforce behaviors that are essential for the individual’s survival and the survival of the species. Because they facilitate the same learning processes as natural rewards, drugs easily trick that circuitry into thinking they are more important than natural rewards like food, sex, or parenting.

What the brain disorder model, within the larger biopsychosocial framework, captures better than other models—such as those that focus on addiction as a learned behavior—is the crucial dimension of interindividual biological variability that makes some people more susceptible than others to this hijacking. Many people try drugs but most do not start to use compulsively or develop an addiction. Studies are identifying gene variants that confer resilience or risk for addiction, as well as environmental factors in early life that affect that risk. This knowledge will enable development of precisely targeted prevention and treatment strategies, just as it is making possible the larger domain of personalized medicine.

Some critics also point out, correctly, that a significant percentage of people who do develop addictions eventually recover without medical treatment. It may take years or decades, may arise from simply “aging out” of a disorder that began during youth, or may result from any number of life changes that help a person replace drug use with other priorities. We still do not understand all the factors that make some people better able to recover than others or the neurobiological mechanisms that support recovery—these are important areas for research.

But when people recover from addiction on their own, it is often because effective treatment has not been readily available or affordable, or the individual has not sought it out; and far too many people do not recover without help, or never get the chance to recover. More than 174 people die every day from drug overdoses. To say that because some people recover from addiction unaided we should not think of it as a disease or disorder would be medically irresponsible. Wider access to medical treatment—especially medications for opioid use disorders—as well as encouraging people with substance use disorders to seek treatment are absolutely essential to prevent these still-escalating numbers of deaths, not to mention reduce the larger devastation of lives, careers, and families caused by addiction.

Addiction is indeed many things—a maladaptive response to environmental stressors, a developmental disorder, a disorder caused by dysregulation of brain circuits, and yes, a learned behavior. We will never be able to address addiction without being able to talk about and address the myriad factors that contribute to it—biological, psychological, behavioral, societal, economic, etc. But viewing it as a treatable medical problem from which people can and do recover is crucial for enabling a public-health–focused response that ensures access to effective treatments and lessens the stigma surrounding a condition that afflicts nearly 10 percent of Americans at some point in their lives.